In the music blogosphere, the sales pitch for Robyn’s self-titled album went something like this: Hey, remember Robyn? That Swedish teenager who had that song called “Show Me Love”? No, not that song called “Show Me Love.” That was Robin S. She’s not a Swedish teenager. Yes, I agree, that song ruled. But remember how there was another song called “Show Me Love,” and it was also a big radio hit, and it came out around the same time, and the two singers had pretty much the same name? Yeah, in retrospect, that was weird. Anyway, the other Robyn has her own label now, and she makes really winky and fun electro-pop, and sometimes her songs are almost upsettingly emotional.

This was not an easy sell, and it took a while for people to really latch onto what Robyn was doing. I had to see her name pop up on a lot of MP3 blogs before I fully realized that I really, really liked the songs I was hearing from her. In retrospect, that’s crazy. Robyn’s self-titled album, which turns 20 on Saturday, is one of the most immediately lovable pop albums of this century. It represents a complete version of auteurist Euro-pop, something that the music dorks of the mid-’00s didn’t even realize was possible. Two decades later, it’s clear that Robyn accomplished something momentous with that album. She pioneered the entire idea of the underground pop star, the cult figure who makes songs that could work as alternate-universe drive-time radio anthems but that instead lead to daylight-hours bookings at indie-centric music festivals. And Robyn turned out to be so good at being an unpopular pop star that she fucked around and became real-deal popular all over again. The sales pitch wasn’t obvious, but the end product was.

Before Robyn could become a cult-pop star, she had to flirt with actual pop stardom. Twenty years ago, Robyn’s childhood history with chart success could’ve been a strike against her. Usually, familiarity is a help, not a hindrance. But Robyn landed two major American chart hits in the late ’90s, in a radio-pop climate where you weren’t necessarily supposed to know anything about the artists responsible for hits like that. Songs like “Show Me Love” — Robyn “Show Me Love,” not Robin S “Show Me Love” — did not get written up in magazines like SPIN, and there was no effort to establish the importance of the kid who might be singing those songs. The hits were treated as product. The Robin S “Show Me Love” felt slightly different, since the singer had the kind of gospel chops that immediately register to American audiences and since there was a clear line between the production and underground club music, but none of that kept her from one-hit wonder status. The Robyn “Show Me Love” didn’t have any of that stuff going for it.

In retrospect, Robyn was the second time that Robyn helped bring about a sea change in pop music. The first time happened when she was still a literal child. As a kid, Robin Carlsson spent years on the road with her parents’ experimental theater troupe, and she had a hard time getting used to stationary living when her parents’ marriage ended. Robyn wrote her first song at age 11, and it was about her parents’ divorce. She sang that song at a school assembly, and Meja, singer of the Swedish band Legacy Of Sound, heard her and introduced her to her first manager. I get the feeling that this kind of thing happens all the time in Sweden — that melodically gifted kids get scouted the same way that athletic American kids get shuttled right into the AAU system. (Robin Carlsson changed her stage name to Robyn to avoid confusion with Robin S; it didn’t work. A decade later, Robyn Rihanna Fenty started going by her middle name to avoid confusion with this Robyn, and that did work, at least in part because Rihanna did not introduce herself with another song called “Show Me Love.”)

Robyn was 15 when her debut single “You’ve Got That Something” came out and landed on the Swedish pop charts. Like a lot of Robyn’s early tracks, it’s a Scandinavian attempt at the kind of breezy and cute R&B that young American singers like Brandy and Shanice were making around the same time. Her next single “Do You Really Want Me (Show Respect)” was a #2 hit in Sweden, and it got her career rolling internationally. She recorded her singles “Show Me Love” and “Do You Know (What It Takes)” with Denniz Pop, founder of the Stockholm hit factory Cheiron Studios, and with Pop’s protege Max Martin. Robyn co-wrote “Show Me Love” with Max Martin, and it was one of his first major international hits. In 1997, two years after they were first released, both “Show Me Love” and “(Do You Know) What It Takes” became top-10 crossover hits in America. Those songs even got play on R&B radio; lots of people didn’t even know that Robyn was white.

Today, you can listen back to Robyn’s 1995 debut album Robyn Is Here and hear Y2K-era mega-pop taking shape before your ears. Soon after its release, Max Martin would craft similar singles with American acts like the Backstreet Boys. Both of Robyn’s hit singles went gold, and Robyn Is Here went platinum. At the time, though, Robyn might as well have been Gina G or Mark Morrison or Donna Lewis or Az Yet or Chumbawamba. You could love her songs and never spend one second thinking about the person who made them. At one point, Britney Spears was supposed to be the American Robyn. I’ve seen record-executive quotes about how Max Martin was excited to work with Britney Spears because she was pliable, whereas Robyn was too headstrong. She wanted too much control.

Robyn’s 1999 sophomore album My Truth was a platinum hit in Sweden, but it never got an American release. Reportedly, one of the big reasons was that she sang about the abortion that she got when she was 18. She wouldn’t remove those lyrics for the US market, so she was effectively locked out of the Y2K teen-pop boom that her first album helped catalyze. After that, Robyn parted ways with BMG, her label, and signed with Jive. She thought Jive understood her artistry better, but then BMG bought Jive. She couldn’t escape her clueless bosses. The same thing happened with her third album, 2002’s Don’t Stop The Music: Platinum success in Sweden, no American release. But one day, Robyn found something new while flipping through records in a Stockholm store. That’s where she discovered the Knife, a Swedish duo who made harsh and uncompromising dance-pop and who released it on their own label. Robyn was intrigued.

Robyn went into a songwriting session with the Knife, and they told her all about releasing music independently. Together, Robyn and the Knife made “Who’s That Girl,” the buzzing, percolating banger that would serve as the blueprint for the music that Robyn would make going forward. There is very little R&B to be found on “Who’s That Girl,” though maybe the song carries a distant echo of the experimental productions that Timbaland and the Neptunes were making around the same time. But “Who’s That Girl” doesn’t really sound like the Knife, either. It’s Robyn singing warmly and sincerely about societal pressures, about not being the girl that someone else dreams of. There’s an immediacy to her vocal, a vulnerability. You had to be a pop star to sing and write a song like “Who’s That Girl,” and you also had to be sick of the expectations that come with pop stardom.

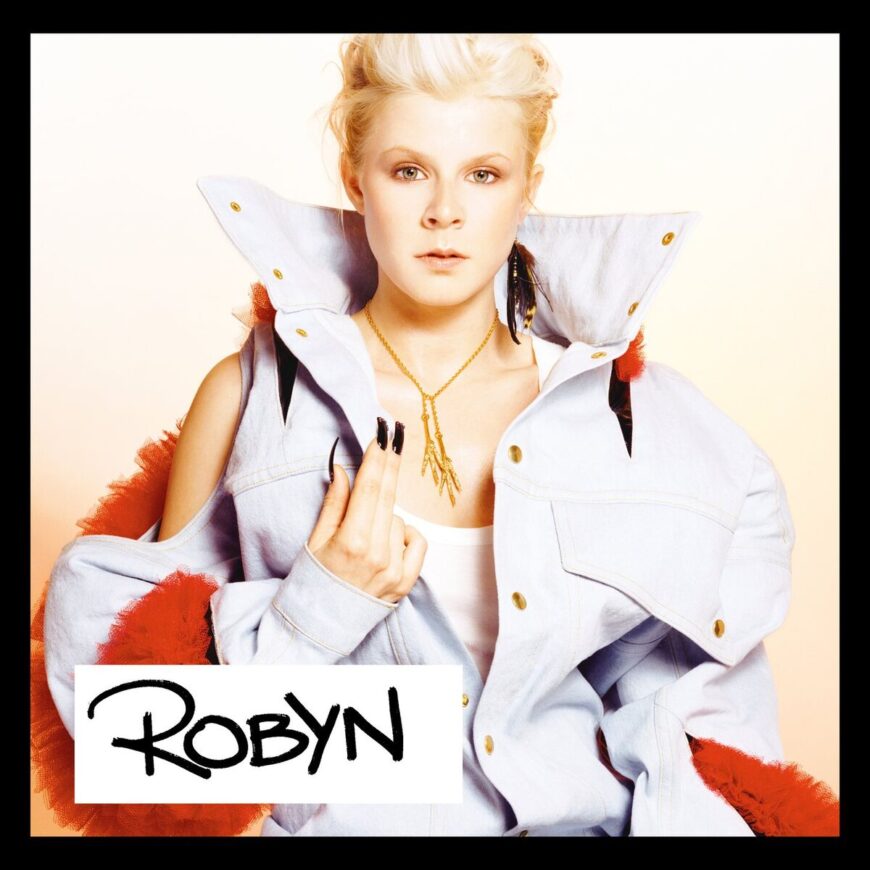

Naturally, Robyn’s label hated “Who’s That Girl,” so she bought her way out of her Jive contract and sank her money into launching Konichiwa Records, her own label. At that point, Robyn was a seen-it-all music-business veteran, and she was 24 years old. She went to work with producer and co-writer Klas Åhlund, a member of the Swedish dance-rock group Teddybears who would later work with people like Katy Perry and Usher. They started messing around with club sounds and pushing each other, and they came up with a set of bright, brilliant pop songs. The tracks on Robyn are knowingly silly and ecstatically emotional at the same time. They feel raw and homemade, but their melodic turns have an ear-pleasing precision that strikes me as being extremely Scandinavian. Robyn reintroduced herself to Swedish audiences with “Be Mine!,” a shimmer-blinking anthem about struggling and failing to get over heartbreak. Åhlund originally wrote the backing track on guitar, but Robyn got him to use strings for the main riff instead, convincing him by playing Kate Bush’s “Cloudbusting” for him. “Be Mine!” is the first song that they made together.

“Be Mine!” was a top-five hit in Sweden, and I’m pretty sure I first heard it when Matthew Perpetua posted it on Fluxblog, shortly after its release. The time was right for a song like that one. On the music blogosphere, writers were chasing down obscure tracks that sounded like they could be pop hits. When the Norwegian singer Annie released her 2004 album Anniemal, one of its selling points was that some of Annie’s songs were actual real-deal hits in Norway. M.I.A. and the Knife got the same kind of coverage. They made mutant takes on chart-pop that reminded younger critics of the ’80s synthpop smashes that we’d loved as kids. Robyn seemed to fit into that bucket, with the strange added backstory of her half-forgotten American pop success. Robyn had no distribution in America; you couldn’t even get it on iTunes. That probably made it more attractive to critics at sites like Pitchfork and Stylus. When you wrote about Robyn, you felt like you were letting people in on a very fun secret.

The disconnect was new. American critics thought of Robyn as an underground phenomenon, but she was still a huge deal in Sweden. She continued to move in the same circles as mainstream hitmakers. At one point, my friend Nitsuh Abebe interviewed Robyn for Pitchfork, and he had to stop Robyn when she mentioned the parties where people like Max Martin and Peter Björn & John would compare the melodies they’d written. It was weird for us to think about a place on the planet where those people might be considered peers. But Robyn’s songs were too sticky to remain unheralded for long. In 2007, Robyn teamed up with the Swedish electro-pop producer Kleerup on the swirling, stirring one-off single “With Every Heartbeat.” That song didn’t do anything in America, but it became a freak chart-topper in the UK.

Robyn was funny, too. That helped. Her self-titled album was big with critics and blog kids when it first came out in 2005, but it didn’t get an American release until two years later. The superior international version of Robyn had a bunch of bonus tracks, like “With Every Heartbeat” and “Dream On,” her gorgeous 2006 team-up with the late Swedish producer Christian Falk. Eventually, Robyn got a distribution deal through Interscope, returning to the major-label system but keeping her indie autonomy. Over here, the lead single from the two-year-old album was “Konichiwa Bitches,” the defiantly silly joke-rap that opens the LP: “You want a thrilla in Manilla? You’ll be killer-bee stung/ You wanna taste the vanilla? Better watch your tongue!” Don’t even ask her about her bada-boom-boom.

You could groan or roll your eyes at Robyn’s English-as-a-second-language punchlines and her Gwen Stefani-esque pop-Japanese imagery, or you could slot her alongside that moment’s wave of hipster joke-rap alongside Fannypack and Uffie and future Robyn collaborators the Lonely Island. But Robyn was having so much fun that nobody could begrudge her, and her non-“Konichiwa Bitches” tracks hit a lot harder once they sank in. Even something as goofy and flirty as “Bum Like You” feels almost achingly romantic if you hear it at the right moment. Robyn had lots of secret weapons working for her, too — the throbbing physicality of the house music that she loved, the ’90s R&B runs that could fly in out of nowhere. She wasn’t a parodist. She was a pop scientist.

Today, Robyn sounds like a readymade greatest-hits album, even though Robyn’s biggest cult bangers wouldn’t arrive until her next record. The songs from Robyn never became mainstream American hits, but they soaked in. If you were sufficiently plugged-in, you might hear those tracks in clubs, at parties, on mix CDs and iPod playlists from friends. They became a part of your life, as if they were actual pop songs. Because of the delayed-rollout international release, Robyn toured behind that album for a solid three years. In America, she played clubs and got ecstatic blog write-ups, and she helped people get their mind around the idea of the pop star who wasn’t actually popular on a mainstream level — pop as a genre, not as a catchall term for music that’s popular. Today, that’s a little zone is thriving, and actually popular pop stars like Charli XCX and Chappell Roan come from the cult-pop ranks.

Robyn is actually popular now, too — popular enough to sing with David Byrne at the SNL50 concert and to quasi-rap about her pre-internet fame on Charli XCX’s “360” remix. On the increasingly rare occasions that she releases new music and tours the world, she plays massive venues. The crowds of Robyn fans singing on New York subway platforms after she headlined Madison Square Garden made for euphoric viral-video fare in 2019. Robyn wasn’t the first of the unpopular pop stars, but she was the one who lasted the longest, who turned it into something. She figured out her own lane. Twenty years later, that lane might be the brightest creative zone on the entire landscape of global popular music. These days, the Robyn sales pitch is a whole lot simpler. She’s your favorite pop star’s favorite pop star. She’s the best.