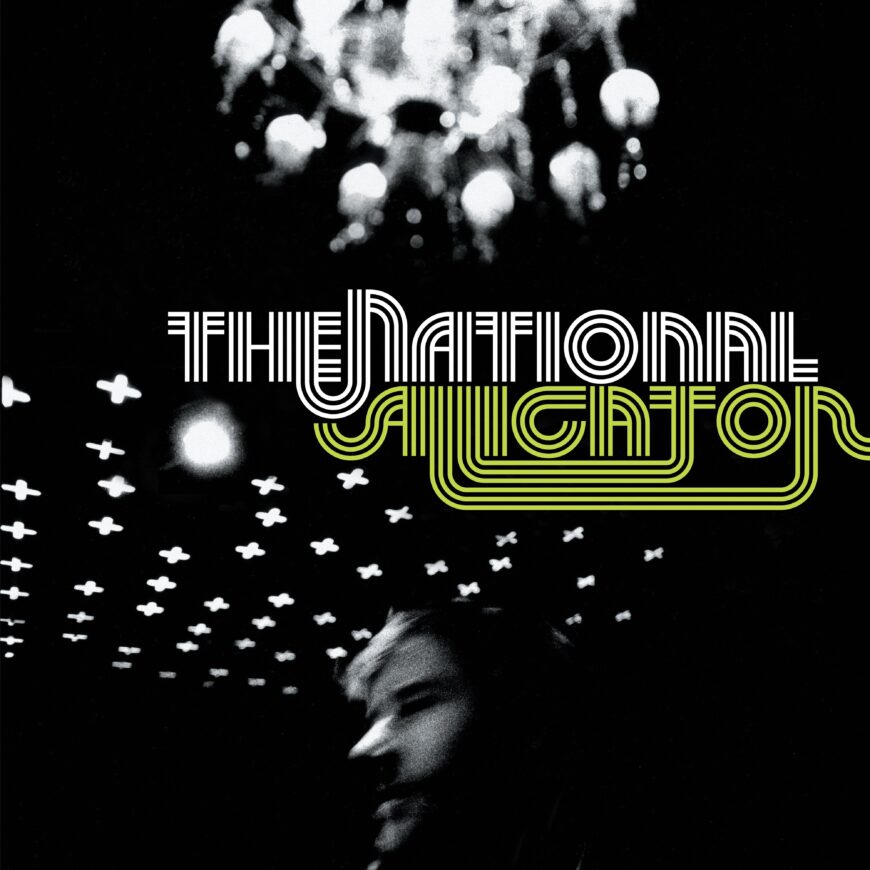

You can hear them becoming the National in real time. That picture of Matt Berninger on the cover is a little blurry, which feels right because the band as we now know them wouldn’t properly come into focus until the next album. But on Alligator, the suave and mangy masterpiece they released 20 years ago this Saturday, it’s happening before your ears: These five guys from Ohio are figuring out an approach to indie rock that will launch them to stardom and, for better or worse, change the genre forever.

Really, they’d already spent half a decade figuring it out — slowly, surely honing in on an unmistakable aesthetic. It had been well over a decade if you count their years in separate units, plying their trade in the dive bars of the ’90s Midwest. Berninger and bassist Scott Devendorf moved to New York first, leaving behind their lo-fi garage band Nancy. (“We started making songs together because we were all obsessed with Silver Jews and Pavement and Guided By Voices,” Berninger once recalled, and you can tell.) Before the end of the millennium, Scott’s brother Bryan also moved up to the city with twins Bryce and Aaron Dessner, his former bandmates in Project Nim, who’d been doing sort of a 10,000 Maniacs thing.

In a rat-infested Gowanus loft, the National first took shape, merging those scrappy Nancy tendencies with the more clean-lined, prim-and-proper aspects of Project Nim. Dropping weeks after Is This It, the self-titled debut was a loosely rootsy R.E.M.-meets-Leonard Cohen concept completely out of step with the New Rock Revolution. 2003’s Sad Songs For Dirty Lovers was slightly sharper and more memorable (“Fashion Coat” remains my jam), but 2004’s Cherry Tree EP was the eureka moment. It had the gorgeous, minimal “Wasp Nest,” the solemnly orchestrated “All Dolled-Up In Straps,” the surprisingly intense “Cherry Tree.” It had “About Today,” a conversational ballad about a romance on the brink that helped to set the template for many future desolate smolders. Crucially, it had “All The Wine,” the song where Berninger perfected the loopy, swaggering persona that so often balances out the National’s dark nights of the soul.

“All The Wine” rules. It’s so good that they decided to include it on Alligator too. It begins with the hopeful twinkle of interlocking guitars, the sound of the Dessner brothers in their bag. When the rhythm section kicks in, the music moves with a contagious sense of purpose, like the moment when the mood shifts in the room and an amazing night begins to unfold. Berninger channels his drunken confidence into a procession of images so vivid you can see him marching down the middle of the road, sloshed and elated: “I’m put together beautifully/ Big wet bottle in my fist/ Big wet rose in my teeth/ I’m a perfect piece of ass/ Like every Californian/ So tall I take over the street/ With high-beams shining up my back/ A wingspan unbelievable/ I’m a festival/ I’m a parade/ And all the wine is all for me.”

The National had tapped into something special, and on Alligator they continued to mine it out. Although producer Peter Katis was now in the fold, the refined splendor that would settle in on 2007’s Boxer was not yet in place — that faint glow that made every song from “Fake Empire” onward sound like prestige TV. Even the dramatic swoons still had some of the raw, mid-fi quality of the band’s early recordings, and the unhinged rock songs were more gritty than grandiose. It’s why this phase of the band’s gestation is some people’s favorite: the rapidly evolving majesty not quite yet outweighing the sense that you’re listening to a phenomenal rock band (one that famously blew openers Clap Your Hands Say Yeah off the stage when the bands toured together in 2005, even on nights when much of the audience filtered out after watching the buzzy blog-rockers).

There’s plenty of languor to go around here, much of it spectacular, but the fuzz-bombed rockers are likely what Alligator zealots think about when heralding the album as the National’s peak. These songs are outliers within the band’s catalog; together they comprise a mostly unexplored pathway to an alternate timeline in which the band drowns its neuroses in euphoric distortion. Later tracks like “Terrible Love,” “Sea Of Love,” and “Eucalyptus” are slathered in noise at the National’s live shows, but on their records the carnage is restrained, as if they’re worried about scaring off the tamer corners of their fan base. Similarly, songs like “Squalor Victoria” and “The System Only Dreams In Total Darkness” have a serious oomph to them — a drum kit hates to see Bryan Devendorf coming — but they lack the feral intensity that courses through Alligator’s most aggressive moments.

The National released more holistically awesome albums down the line, but I get why people would long for more of the cataclysmic power they served up here. “Lit Up” achieves liftoff on the chorus, Berninger buoyed by liquid courage and a surge of harmonic clamor. “Abel” is off the chain from the beginning, in no small part thanks to some of the harshest, most wild-eyed vocals to ever grace a National song. But no song looms larger in the National’s road-not-taken canon than “Mr. November,” a nonstop endorphin rush that always seems to be building, building, building toward ecstatic release (except when, holy shit, it’s arriving, wow, wow, wow). Sung from the perspective of a blue-blooded political candidate who repeatedly promises, “I won’t fuck us over,” it’s the kind of political satire many bands would play for laughs, but the National opt for exhilaration, blurring the line between empty campaign-trail rhetoric and genuine do-gooder optimism.

If the National were emerging as a force of nature, they were also coming into their own in subtler, more sophisticated ways that would endure within their discography. The string arrangements that colored the edges of songs like “Val Jester” had been there on past releases, but the band was finding less conventional ways to convey maturity too. On “Karen,” the midtempo weariness that had sometimes fallen flat on past albums instead took on a cinematic quality. The ballad “Daughters Of The Soho Riots” moved with a graceful simplicity, the band conjuring a plaintive atmosphere with little more than some crystalline chords and gentle thudding. Opener “Secret Meeting” glittered out of the gate, then decorated its four-chord build with distant shouting, as if one of the band’s old Gowanus loft parties is breaking out in the middle of a triumphant U2 song.

“Secret Meeting” also stands out as further evidence of Berninger making the leap as a lyricist. “Didn’t anybody tell you how to gracefully disappear in a room?” he wonders, before conceding, “I’m sorry I missed you/ I had a secret meeting in the basement of my brain.” No such missed connections on “The Geese Of Beverly Road,” with its story of a couple giddily setting off car alarms (“Hey, love, we’ll get away with it/ We’ll run like we’re awesome, totally genius”) and getting up to other kinds of misbehavior (“We’re drunk and sparking, our legs are open/ Our hands are covered in cake/ But I swear we didn’t have any/ I swear we didn’t have any”). Similar exploits surely await on “City Middle,” with the wheels greased by just the right cocktail of substances: “I’m on a good mixture, I don’t want to waste it.”

Berninger was becoming the baritone bard for an era marked by apps and anxiety, recessions and vape pens. He mapped out the ennui of no-longer-young adulthood in bursts of surreal imagery and plainspoken vulnerability, each song a little arthouse rom-com unto itself, glorifying and skewering the tasteful yuppie class that the band and its core audience belongs to. His sidelong way of conveying these sentiments — and the deep, craggy voice that delivered them — was as crucial to the band’s success as their fine-tuned aesthetic. The songs simply wouldn’t hit the same without their quirky, depressed leading man carrying on about spilled drinks and fancy clothes, earnest to a fault but unafraid to make himself the butt of the joke.

For a crash course in Berninger at his best, look no further than “Baby We’ll Be Fine,” a clean-toned tempest that technically sounds like early National but lands with the impact of the band at its peak. It boasts an all-purpose ultra-catchy refrain in “I’m so sorry for everything” — a phrase anyone could latch onto — but also lots of hyper-specific, hyperreal scenes of a grownup bordering on a breakdown: “All night I lay on my pillow and pray/ For my boss to stop me in the hallway/ Lay my head on his shoulder and say/ ‘Son, I’ve been hearing good things’/ I wake up without warning/ And go flying around the house/ In my Sauvignon, fierce, freaking out/ Take a 45-minute shower and kiss the mirror.”

Songs like that one make it obvious in hindsight why the National took a while to cohere and even longer to break through. “We look younger than we feel and older than we are,” Berninger sang on Sad Songs For Dirty Lovers, charting a course toward the rumpled-but-refined grandeur that would become the band’s ethos, influence a whole generation of dinner-party indie bands, and ultimately ripple out to the upper reaches of pop stardom. The National’s true calling was to voice the quiet desperation of white-collar creatives aging out of their youthful prime, into the years when you start to wonder about what might have been and worry about where all this is headed. Berninger was 34 when Alligator came out. I’m not sure he could have written the songs that captured these particular hopes and humiliations any earlier in life. But here, on the brink of midlife, he and his bandmates were zeroing in.