There’s a recent Chris Fleming standup bit that kicks off with him chastising a friend for daring to have a crush at a time like this.

“A CRUSH?” Fleming roars, “A crush is for a time of prosperity! How is your nervous system even relaxing enough to allow a crush? No time for a crush! Now, you need to KNOW.”

If there was ever a time for a crush, maybe it was the summer of 2012, that odd little era where the 2000s were still becoming the 2010s, a time marked by a post-recession shift towards earnestness and the peak of the Obama years, when the undisputed Song Of The Summer was Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe.” It was inescapable — a relic of a monoculture that, 13 summers later in this fractured present, feels unthinkable. It was covered and parodied and mashed-up and lipsynched to death. The “Call Me Maybe” Summer — the one that transformed Carly Rae Jepsen from a former Canadian Idol hopeful into a full-fledged pop star — took place between my middle school graduation and my freshman year of high school (somewhere in my childhood home I’ve still got the eighth grade yearbook with MULTIPLE “Call Me Maybe”-quoting signatures, artifacts of the song’s ubiquity).

I spent a couple weeks of that summer at an all-girls YMCA sleepaway camp in a tiny town on the South Shore of Cape Cod. Campers were forbidden from using any technology during our time there, and we greedily gobbled up the few crumbs of contemporary pop culture that managed to sneak their way into our unplugged lakeside enclave. Teen magazines that we got in our care packages with full fold-out posters of Justin Bieber and Robert Pattinson that we plastered to our cabin walls. Gossip from some college girl counselor who’d come back from time-off claiming to have spotted Taylor Swift with a Kennedy boy in Hyannis. And, of course, the Top 40 radio hits.

“Call Me Maybe” boomed from the speakers flanking the lifeguard’s chair while we splashed around in glassy green lake water and rubbed coconut-scented tanning oil on each others shoulders; from the puff-painted stereo in the Arts & Crafts house where we weaved friendship bracelets and tie-dyed T-shirts; from the DJ booth at the camp dance — the one night where they’d bring pontoon boatloads of boys from our brother camp across the lake so we could awkwardly shuffle around on the tennis courts with them, unable to make eye contact. At 13, I’d already begun to track the eras of my life in the music and pop culture that dominated them, and whether I liked it or not (at first I didn’t, but gradually it grew on me) I can’t remember the summer of 2012 without hearing the opening notes of “Call Me Maybe.”

I know I’m not alone in this. Hell, it’s probably true for Carly Rae Jepsen herself. “Call Me Maybe” put Jepsen on the map, but Kiss, its accompanying album, though critically well received, was not the breakthrough that it was perhaps intended to be. Follow-up single “Good Time,” featuring Owl City, was lackluster in comparison, and it was the only other track on the album that charted in the Billboard Top 40. Even her then-manager, Scooter Braun, admitted that the album failed to live up to the standard set by its lead single.

Following Kiss, Jepsen made her Broadway debut, starring in Rodgers And Hammerstein’s Cinderella, where she bonded with costar Fran Drescher over the experience of having one relatively early high watermark overshadow one’s entire career. The Nanny was Drescher’s “Call Me Maybe.” The show and the single were career-defining hits for Jepsen and Drescher respectively — and pretty damn great ones at that. The other day I rewatched, in succession, the music video for “Call Me Maybe” and the pilot of The Nanny — both still fun, bubbly, and timelessly charming. To create something so lovable early on in your career that it defines all that follows in the eyes of the public is a blessing and a curse, but both Jepsen and Drescher have proven that there’s a way to refuse to let your mainstream peak be the peak of your artistry.

If she wanted to, Carly Rae Jepsen could never write another song again and probably be set for life with the “Call Me Maybe” royalties. But she very much does want to keep writing songs — and she’s good at it. For a decade-plus, Jepsen’s career has been in the sweet spot where she’s got the resources, connections, and critical goodwill to pretty much make whatever she wants without worrying about commercial appeal. Who else could play the main stage at Pitchfork Music Festival twice, play Frenchy in Grease, Live! with a new song added to the show specifically for that role in that production, get Tom Hanks to star in a music video, co-write a musical adaptation of a 10 Things I Hate About You with Jessica Huang and Lena Dunham, and appear alongside the likes of Xiu Xiu and Death Grips on Spotify mixes and last.fm grids alike?

Add to that the fact that she can reap the benefits of fame while getting to live a quasi-normal life. I’m sure Jepsen gets recognized by strangers fairly often, but probably not so much that it’s untenable. She can probably go to the supermarket like a normal person and then bring her artisanal organic groceries (I assume) back home to her swanky apartment. She falls into a similar niche as a star like Kylie Minogue or Robyn, who’ve proven that the best level of fame you can achieve as a woman is the kind where the general public doesn’t have more than a vague idea of who you are but a small yet devoted fanbase of gay guys would die for you. A little over a year ago, Dirt published a roundup in which they asked people what the ideal level of fame was. Jepsen was the impetus for the prompt itself.

been thinking about it and folks seeking fame should stop at carly rae jepsen level. perfect fame. great concerts. loving fans. don't know anything about her personal life. no notes.

— Rebecca Fishbein (@bfishbfish) April 19, 2024

Maybe Pop’s Middle Class (or, to use a less charitable slang term, the Khia Asylum) isn’t such a bad place to be. In the past couple years we’ve seen a few former mainstays of that lane like Sabrina Carpenter and Charli XCX enjoy mainstream breakthroughs, opening them up to endlessly tiring thinkpieces and the danger of overexposure. Sometimes, there’s a moment where a one-hit wonder becomes a two-hit wonder that doesn’t manifest in full-on household name status (think Tinashe having a viral hit with “Nasty” during the summer of 2024). But maybe there’s a certain type of freedom and pop-star cred that’s only accessible for those who remain on the fringes.

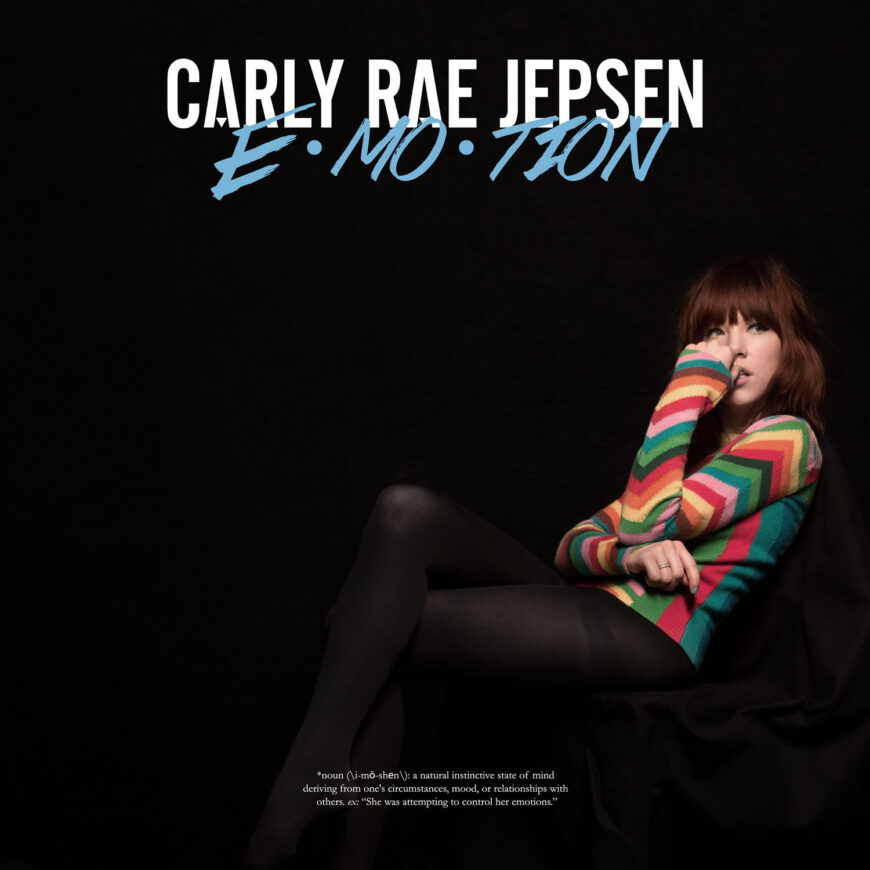

E•MO•TION — first released 10 years ago today in Japan before officially landing in the US two months later — is arguably the album that defined Pop’s Middle Class before Shaad D’Souza ever coined the term, and it makes sense that so much of it is a result of Jepsen taking cues from fellow if-you-know-you-know underdog pop stars. She named Solange’s “Losing You” as a major influence. In the same way that the average person has probably either never heard of Carly Rae Jepsen or knows her as “the ‘Call Me Maybe’ girl,” Solange is “Beyoncé’s little sister” to most. It’s an unfair designation but an understandable one. And while Beyoncé is responsible for some of the greatest heartbreak songs of the 21st century, the type of star power that’s as immaculately curated and untouchable as Beyoncé’s could never capture the abject failure that a song like “Losing You” does.

One way to understand the appeal of “Losing You” is to revisit Jack Antonoff’s praise for “Dancing On My Own.” On the eighth anniversary of Robyn’s signature hit, Antonoff tweeted that the song was “a bible” for the type of heartbreak anthem where “the sadness is sewed into the glory.” (It’s worth noting here that Antonoff produced several tracks recorded during the E•MO•TION sessions that never made the album or its B-sides compilation). Now, like any pop music critic with halfway-decent taste, I’ve got plenty of beef with Mr. Antonoff, but I will give the man credit where it’s due. In between all his yes-manning Taylor Swift’s and Annie Clark’s worst musical impulses and the many instances of indiscriminate, vibes-first production choices, he occasionally hits the nail on the head — see: the 2019 Carly Rae Jepsen single “I Want You In My Room,” Lorde’s Melodrama, every record he’s produced for Lana Del Rey, and the aforementioned “Dancing On My Own” tweet.

The sadness is sewed into the glory of “Losing You.” The sadness is sewed into the glory of every hand clap and synth pulse and hazy, bassy meowing noise in the track’s blown-out hip house beat. The sadness is sewn into the glory in each staccato syllable that Solange huffs out at the chorus like a barely-concealed sob. “Losing You” — like “Dancing On My Own” — channels the heat usually reserved for a dancefloor makeout into a dancefloor cry instead. The club’s too crowded to slip away to the bathroom to fix your face in the mirror, so we’re rocking the runny eyeliner look tonight.

Yet another long-lost sister to these tracks, and another swatch on the E•MO•TION moodboard, is Sky Ferreira’s “Everything Is Embarrassing.” Ferreira’s signature song is darker and rougher around the edges than anything Jepsen’s done, with its murky synths, subtle slap bass, and the pitched-down echo backing Ferreira’s deadpanned vocals, but you can hear her influence throwing its shadow behind Jepsen in E•MO•TION’s most heart-wrenched moments. There’s not much overt glory in “Everything Is Embarrassing,” but you can bet that there’s sadness sewed into every glimmer of it.

Solange co-produced “Losing You” with Dev Hynes, and “Everything Is Embarrassing” was co-produced by Hynes and Ariel Rechtshaid, both of whom share instrumental and production credits on E•MO•TION’s glowy mid-album slow-dance “All That.” On “Making The Most Of The Night,” Haim, Rechtshaid’s longtime collaborators, sang backup. (The Haim sisters occupy a similar type of fame as Jepsen — one or two big-enough hits to pay the bills, but unlikely to be mobbed by fans on the regular unless all three of them are together.)

Elsewhere on the record, Rechtshaid shares co-production credits with Dan Nigro, whose production resume is perhaps the most crystalline encapsulation of the trickle-up influence of the alt-pop of the 2010s (Sky Ferreira, Empress Of, Caroline Polachek) on the mainstream pop of the 2020s (Olivia Rodrigo, Chappell Roan). E•MO•TION itself is a microcosm of this influence, with its juxtaposition of bubblegum song structures and delivery with moody synth and pop rock sounds borrowed from the ’80s — and it’s probably as un-dated as a record that includes the line “Buzzfeed buzzards and TMZ crows” could possibly sound (she pulled it off then and still does now).

In addition to their taste in producers, Jepsen shares a talent similar to Solange and Sky Ferreira and many of their sisters in the not-quite-mainstream pop sphere: the ability to make failure and humiliation sound triumphant. “Gimmie Love” and “Making The Most Of The Night” are pure desperation disco; their soaring, head-out-the-window choruses are only possible through emotional self-annihilation. “When I Needed You” is a song of romantic disappointment that finds more catharsis in surrender than scorn. The record’s title track revels in being the subject of a “what could’ve been” fantasy, each teasing synth beat sparking with potential energy.

I’d be hard-pressed to think of a more evocative opening 10 seconds of a record from the 21st century than the “Run Away With Me” saxophone riff. Of all the songs on E•MO•TION, “Run Away With Me” was probably the record’s closest thing to a “hit” song. It’s purely anticipatory, a love story told in hypotheticals: “Over the weekend we could turn the world to gold.” When Jepsen begs, “Baby, take me to the feeling!” at the chorus, she sounds victorious enough to make you forget that the person she’s reaching her hand out to hasn’t taken it yet.

It can be unimaginative to reduce music to its intended demographic, as if many different people can’t love the same record for their own reasons, within their own contexts. Nonetheless, Jepsen and her team were allegedly pursuing one audience in particular on this release: music critics. In the run-up to E•MO•TION, Braun told the New York Times that team CRJ opted “to stop worrying about singles and focus on having a critically acclaimed album.” That’s a suspect framing of a rollout with a lead single, “I Really Like You,” that was seemingly designed to be “Call Me Maybe” redux. But if any part of E•MO•TION was intended to cement Jepsen’s place at Top 40 radio rather than launch her into the pantheon of prestige pop stars she now inhabits, it’s for the best that those efforts failed.

I think of a record like Charli XCX’s Brat, whose songs largely revolved around Charli’s meta-commentary on her own status as someone on the fringes of fame, always on the precipice of a mainstream breakthrough that never quite came. Brat ended up being a self-fulfilling and self-contradicting prophecy, elevating Charli to a level of gen-pop notoriety that had evaded her for the previous decade. In a much less self-aware or straightforward sense, E•MO•TION feels like the retroactive inverse of this trajectory. One might wonder if E•MO•TION — an album defined by unfulfilled desire — would hit quite as hard had it achieved monocultural recognition. The record’s appeal and staying power as a cult classic not only makes up for its lack of instant commercial success, but adds to its overarching themes of wanting without getting.

It would be a disservice to write a retrospective on E•MO•TION that did not mention Hanif Abdurraqib, who is almost as much of a preeminent scholar of crushes as Jepsen is. Abdurraqib has written about Jepsen at length numerous times and could probably write a dissertation on her body of work, but I’d like to highlight his semi-viral PowerPoint presentation on the song “Your Type,” which consists of only one slide that reads in all-caps, “TELL A FRIEND THAT YOU’RE IN LOVE WITH THEM TONIGHT.”

Abdurraqib argues that “Your Type” is the song that most embodies the central idea of E•MO•TION and Carly Rae Jepsen’s songwriting at large: that the emotional value of any compelling love story lies not in the result of one’s desire but the act of desiring itself. “She’s figured out a simple math,” he says. “Once you’ve caught that which you desire, the story is less interesting. She gives us instead a neverending chase where the only thing to fall in love with is the idea of falling in love.” To him, “Your Type” is a song about platonic love as much as it is about romantic love, one where the veil between the two is thin and fragile.

E•MO•TION grants more focus to the latter than the former, but it has a fair share of songs where the bond of friendship ends up being the most crucial one. “All That” builds to the line “I will be your friend” as its grandest romantic statement; the narrator of “Boy Problems” realizes that she’s failing the Bechdel Test and that her closest friendship is suffering for it; “Your Type” is about falling in love with a friend, accepting that this love will go unrequited, but still declaring “I’ll make time for you” — not in a way that suggests holding out hope that this person’s feelings will change, but in a way that recognizes that the importance of the friendship outweighs the pain of rejection.

The listener is offered little in the way of characterization of Jepsen or the object of her affection in favor of zeroing in on the tension between them. Its emotional palette is familiar — predictable, even — and I’ll admit that rhyming “together” with “forever” (as Jepsen does on multiple songs) isn’t the most original or inspired move. This lack of specificity was Corban Goble’s main criticism in his Pitchfork review of E•MO•TION. He wrote that Jepsen came across too anonymous, and that one of E•MO•TION’s greatest strengths — its universality — was also a weakness.

I’ve long believed that in most cases, your crushes reveal more about you than the person you’re crushing on, and that the way you act when you have a crush is — intentionally or not — a means of making a part of yourself known. This is especially true when you’re crushing on someone from afar, or when the crush is unrequited, or there’s no easy, satisfying ending in sight. With a barrier between the crusher and the crush object comes an opportunity to create a sort of composite character pieced together from what you know about this person and what you’ve projected onto them.

I’m not saying this is sustainable. If and when your feelings are reciprocated, a real person enters and disrupts the fantasy, and the truth of that person makes the fiction that held their place no longer necessary. That’s wonderful in its own way, and in the case of an actual relationship, that’s how it should be, but it requires a degree of proximity and reciprocity that isn’t always available. You fall in love with the idea of someone and then — if you’re lucky — you get to fall in love with the person themself. Most crushes only make it to the first fall: they fade out; they go unrequited; the real person ruins the fantasy. But a crush doesn’t always have to be a means to an end. A crush can be its own universe. A crush is a way of introducing yourself to yourself. Carly Rae Jepsen understands all of this, and that’s what she’s doing on E•MO•TION. On this record it is the crush — the feeling — more so than the crush object, that is the living, breathing human animal. It’s the wanting, not the getting, that makes you real.