“There were days when I had no sense of time or reality, and I wasn’t functioning on a practical level, a day-to-day, matter-of-fact level. I was functioning on a supernatural level, in my mind, in my imagination. That was sustained for days and weeks, and sometimes months. It was really exciting. To be in that space that is so personal yet so epic, as well, and so supernatural, I don’t think it’s really healthy for people for long periods of time. It’s very self-consumed. And also self-consuming. But it’s very enjoyable.”

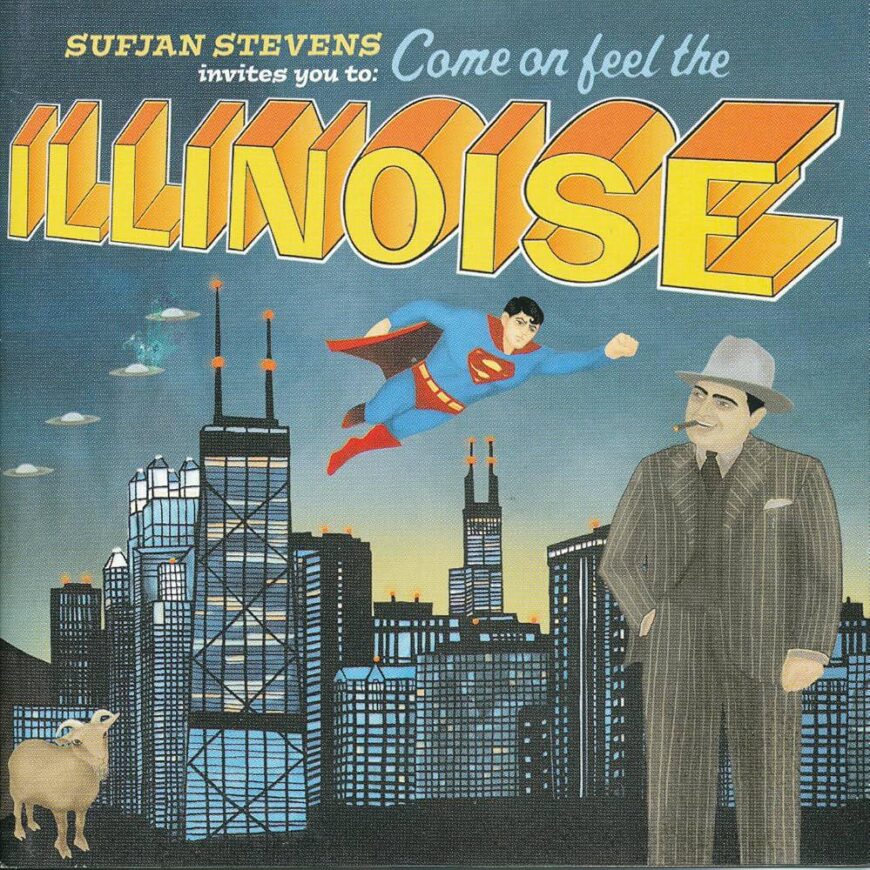

This was Sufjan Stevens talking to Under The Radar in 2005. In a flourish of language that mirrored his voluminous musical output at the time, the singer-songwriter, arranger, producer, and all-around font of creative activity was describing the experience of writing and recording his landmark album Illinois, which turns 20 years old this Friday. Yes, the LP otherwise known as Sufjan Stevens Invites You To: Come On Feel The Illinoise came out on the Fourth of July — a release date befitting a work as sprawling, complex, and pointedly American as this one.

Arriving two years after Michigan, the album that made him a mononymous celebrity among Pitchfork readers, Illinois was the one that helped him reach beyond ultra-online blog denizens and into the realm of MTV News features and Austin City Limits performances, firming up the kind of cult stardom that transcends hype cycles. In the interim, he’d unveiled Seven Swans, a hushed and solemn song cycle centered on his Christian faith. Seven Swans marked an immediate detour from the 50 States Project, an impossibly ambitious endeavor in which Stevens would supposedly release an album for each state in America. But when he came back around with this dense and precocious imaginary travelogue, it suggested that maybe he would really go through with this crazy idea after all.

Nowadays — at a time when Stevens has long since transcended his reputation as the 50 States guy, when mentions of the project are mainly confined to some of the most annoying jokes on your social media timeline — it has become commonplace to suggest that obviously he never intended to actually make an album for every state in the union, that it was never more than a publicity stunt. “I have no qualms about admitting it was a promotional gimmick,” he told The Guardian in 2009. In a 2019 Ringer feature, publicist Daniel Gill recalled concocting the 50 States Project with Stevens as a way to drum up attention at a time when he had no public profile. But the existence of Illinois, in all its high-concept, deep-dive splendor, complicates that picture. Upon impact, the natural reaction was, oh shit, he’s really doing it.

On Illinois, he was doing the most. With Michigan, Stevens had mapped out a vivid landscape brimming with joy and sorrow, portraying his homeland with the lived-in perspective of a local. The album’s stunning depth and scope was matched by a unique musical language pulling from folk, modern classical, indie pop, post-rock, musical theater, and other traditions. He set his trembling tenor loose within a diverse terrain in which the sparse banjo balladry made sense alongside the choral-orchestral maximalism, spinning vignettes about struggling people in pursuit of the divine. It was a rich outpouring of personal expression, its sound bespoke and unmistakable, its procession of names, images, and stories summoned from memory. Whereas Illinois was more like an honor student’s fantastical research project, refracting the culture and history of a place he’d barely visited through layers of sonic and conceptual imagination.

“I did a lot of reading,” he told Dusted. “I read Saul Bellow, a famous Chicago writer. Carl Sandburg, a now kind of outdated poet who wrote the ‘Chicago’ poem, and he wrote a very famous biography of Abraham Lincoln; it’s really long and rambling, and pretty inaccurate as well. I read that, I read some of his children’s books. I read some strange history books; there’s a historian from Illinois who wrote Frontier Illinois, which is about early immigration patterns, surveying Native Americans moving out and Europeans moving in. A lot of picture books from different towns. A lot of these towns will do small runs of memorabilia, artifacts, photos, and things like that about their history.”

It’s not for nothing that on “Come On! Feel The Illinoise!” Stevens assigned backing vocalists Katrina Kerns and Shara Worden to wonder out loud, “Are you writing from the heart?” But if Illinois can often be nerdy and twee, there’s little doubt that he poured his whole self into these songs along with Mary Todd Lincoln, John Wayne Gacy, the wasps, the zombies, and Superman. His religious interests are woven throughout; the chorus of “Chicago” is practically evangelistic. “Come On! Feel The Illinoise!” — a high-concept multi-part anthem about the World’s Columbian Exposition, a visitation from the ghost of Carl Sandburg, and the cost of so-called progress — includes the line, “I cried myself to sleep last night.” Even humble short stories like “Casimir Pulaski Day” are startlingly personal, and reflecting on Gacy’s twisted crimes inevitably leads back to Sufjan grappling with his own sin. At the top of the tracklist, he invites the rest of us to reckon with our own complicity with references to the displacement of the indigenous population and the rampant capitalism that followed — though not until after the UFO touches down.

“Because America is a nation of immigrants, it seemed appropriate to begin with a supernatural visitation,” Stevens told Gapers Block. “My parents were certain, in the mid-’80s, that they were Star People. This would make me an alien offspring, so of course I’ve always been obsessed with outer space. Who isn’t? In general, the Illinois record gives an overarching survey of the history of civilization in that particular region, from the Cahokia Mounds to Native Americans to European immigration to the Industrial Revolution. I needed to step back and get a view from the moon, so to speak. I figured that an inquiry into the civilization of mankind requires the most objective vantage point, namely that of an alien. We are all aliens here.”

Stevens had given himself a staggering assignment, and he responded with an overwhelming amount of music — enough to fill 74 minutes on the main album and another 75 minutes on companion release The Avalanche. Holed up in a studio in Astoria, Queens with his 8-track recorder for four months, he wrote and revised as he went, locking into a flow state, indulging his wildest flights of fancy with chipper assistance from his friends. Despite Stevens’ relatively spartan recording setup, Illinois felt like a hi-fi, big-budget operation compared to what came before it. As he told UTR, the evolution was driven by an enormous amount of self-imposed pressure: “I think what motivated me the most is that with Michigan, I didn’t feel like I’d achieved what I wanted to achieve. I felt like musically there were personal goals that I wanted to meet.”

On Illinois, all the elements from Michigan were back — the soaring strings, the childlike chorales, the banjo, the brass, the woodwinds, the vibraphone, the glockenspiel — but now with traces of rock, country, even funk. The lively parts were livelier, the colorful parts more colorful. We can argue about whether this constituted an improvement; for me, Michigan is perfect and Illinois can be A Little Much at times. But what’s not debatable is that an aesthetic that had previously seemed so downcast now came across as triumphant. Large-scale events like the Great Chicago Fire became launchpads for songs so theatrical they were literally repackaged into a Broadway musical, a framing that had been on Stevens’ mind from the beginning.

“For this one, I was going for kind of a dramatic, Broadway musical style, which was pretty broad; I could do pretty much whatever I wanted to,” he told Dusted. “I wanted it to be a real survey, kind of a historical survey, but I didn’t want it to be heavy with information; I didn’t want it to be too political, and I didn’t want it to be too didactic. So I had to somehow monitor everything with kind of a sense of self-discovery and conviction, and an emotional landscape within me, personally. That was the overall goal of the record. It was kind of ambitious from the start, because I knew I wanted it to be really big and on a grand scale. I wanted it to be almost like a movie soundtrack, but without the movie.”

It sounds like an exhausting undertaking. Inevitably, the thought of making 48 more of these became too daunting to bear, and by the time he spoke to Pitchfork in 2006 upon the release of The Avalanche, he sounded ready to retreat into a time of rest and recalculation. “I’m getting tired of my voice,” he lamented. “I’m getting tired of…the banjo. I’m getting tired of…the trumpet.” It probably didn’t help that, along with peers like the Decemberists and Arcade Fire, he was helping to cultivate an oppressively cutesy, hyper-literate wave of indie bands with an affinity for large rosters and unwieldy proper nouns. Like so many influential artists, he would soon react against what he had wrought.

For the next several years, Stevens disappeared into side projects away from his official canon of albums. When he returned with All Delighted People and The Age Of Adz in 2010, he seemed like an entirely different artist: at the end of his rope, cracked and sobered by the world. The 50 States conceit had been a framework for understanding America and, by extension, himself, but now he’d moved on to new prisms, ones that would eventually be cast aside too once they’d run their course. “I feel like my whole music career has been an exercise in calling my own bluff,” he told Vulture in 2022. “I go on all these excursions and I feel they’re indulgent and slightly megalomaniacal in their approach. At some point, I realize how absurd and unhealthy and unsustainable it is, so I am fine moving on. I think it’s the original impulse that generates the work and allows me to bear down in isolation and create as lavishly as I can, but at some point, you have to go.”