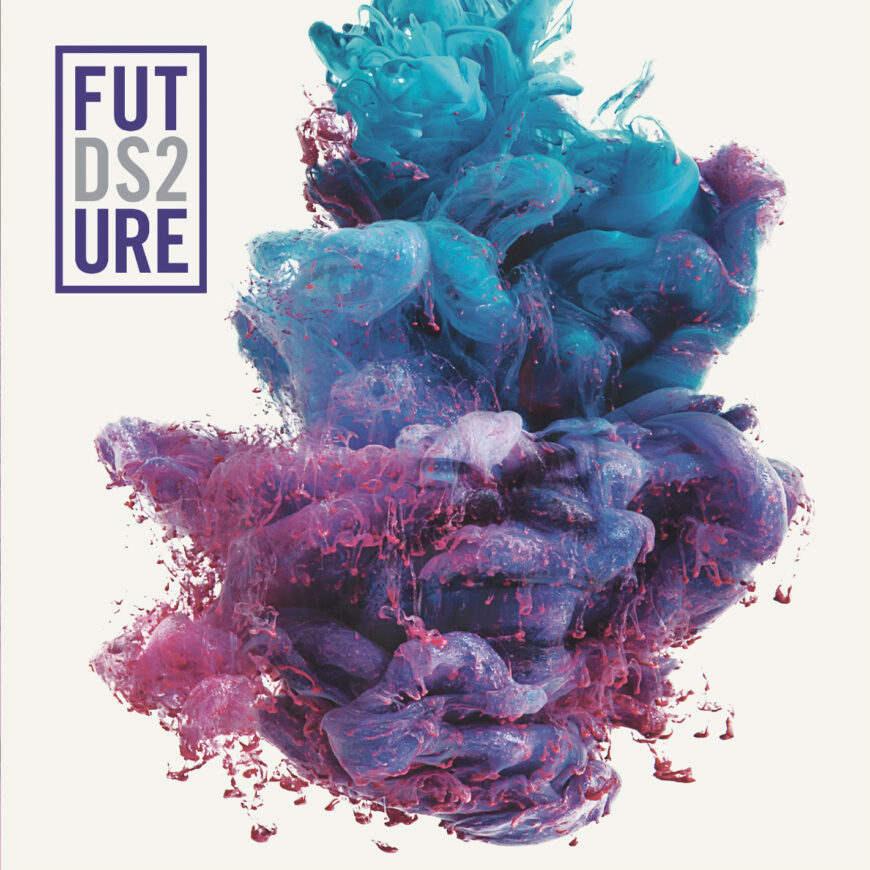

“Best thing I ever did was fall out of love,” Future says near the end of DS2. It’s a quintessential Future line, plainspoken but subliminal, steely but wounded, a flex that’s obviously spin — especially in the context of the bitter and addled music that precedes it. Falling out of love isn’t a choice; like an actual fall, it happens to you, the decision-making taking place after the plummet is underway. But in the topsy-turvy world of DS2, which turns 10 today, everything gets screwy: cause and effect, joy and pain.

The hypnotic 2015 album, Future’s best, capstoned a mixtape run rivaled by those of Lil Wayne and Gucci Mane in the aughts. But at the top of 2014, the Atlanta rapper hadn’t “decided” to fall out of love just yet. He was engaged to Ciara and on the verge of releasing his eclectic sophomore album Honest. The months ahead seemed promising: the couple was expecting, singles were charting, and Future was landing features with A-listers like Miley Cyrus and Justin Bieber.

But then the dream collapsed. Ciara and Future broke up, reportedly due to his infidelity. Then Honest didn’t do well commercially, and Future felt increasingly out of place in Los Angeles. “It’s a dream to come from where I come from and say you have a house in Beverly Hills, but I’m not happy,” he told MTV News. “This not who I am. I don’t like walking outside and walking my dog.”

He decamped home to Atlanta to get his bearings and escape the spotlight, holing up in the studio for marathon recording sessions. “I never seen anybody make music like him,” producer Southside once said. “Like, if I send him 20 beats, Future would make 20 songs then ask me to send him 20 more.” The breakup and the accompanying notoriety gave him lots to process, and back in his element, he found a groove. He’d pull up to the studio and rap for hours and hours as trusted beatmakers like Southside, Metro Boomin, and Zaytoven fed him instrumentals.

The work paid off. Over five months beginning in late October 2014, he dropped Monster, Beast Mode, and 56 Nights, each tape distinct in sound and narrative. The quality and growth were astonishing. Future was evolving in real time, his vocals and flows growing slinkier and more emotive, his narratives sharpening. He was brokenhearted and vindictive and outraged, constantly finding new ways to express that flux. Growls, snarls, murmurs, and croaks entered his already expansive vocal repertoire. He was becoming a monster.

Future pitched the pivot back to mixtape experimentation as a homecoming, saying he felt compelled to please his core audience after literally going Hollywood. But it would be a stretch to call any of these mixtapes fan service. The songs bore little resemblance to the cheery swag rap and bouncy dopeboy anthems of 2011’s Dirty Sprite, Future’s breakout mixtape. And they deviated from the fun-forward party cuts being made by peers like iLovemakonnen, Rae Sremmurd, and Young Thug. While the drums and melodies on these tapes hit like club music, the mood was gothic and brooding, the constant debauchery more deadened than cathartic. It feels appropriate that Future recorded a lot of these songs at a studio nicknamed the Batcave. Even the looser cuts, like “Peacoat” from Beast Mode, feel cold and solitary, Future alone in darkness, the trap Bruce Wayne.

DS2, released just four months after 56 Nights, pushed further into this monkish new mode. There’s just one feature compared to the dozen-plus on the original Dirty Sprite, and no skits, not even a Big Rube interlude. The record kicks off with the sound of a double cup being poured, and then we’re deep in Future’s narcotized mind. It’s a numb and melancholy space, a far cry from the jolly bounce of the Dirty Sprite title track. “I just took a piss and I seen codeine coming out/ We got purple Actavis, I thought it was a drought,” Future raps with groggy vacancy. The couplet is eerie. Future doesn’t feel the drug leaving his body; he sees it, like he’s watching his life rather than living it. The flex that follows that detached perspective makes it even more unnerving. “This could be you but you’re broke,” he taunts, as if excreting purple liquid into a toilet is the pinnacle of the American dream.

Maybe it is. Future spends the record downing weed, lean, and pills in copious amounts while narrating miserable flings with the same enthusiasm he had for that time he saw codeine coming out his dick. He brags a lot, blowing a bag a day, putting famous chicks in “rotation,” and fucking up commas — activities generally not enjoyed by the wider public. But you have to squint to find much pleasure or any other kind of feeling. “I appreciate the way you fuck me!” Future yells, on “Groupies,” a thunderous track that makes bachelor life sound like CrossFit. It’s one of the album’s few humorous moments, but the exception proves the rule. There’s little distinction to parties and highs and hookups he cycles through. Even strippers, a plank of Atlanta rap, lose their charm as Future spins in place: “I just did a dose of Percocets with some strippers,” he says matter-of-factly.

The tormented rich man is a familiar story, but Future makes it deliciously weird. The intensity of his numbness wavers, producing jarring tonal shifts and loud ironies. He’s arch and defiant on “Slave Master,” chanting “Long live A$AP Yams, I’m on that codeine right now.” But even for a no-fucks-given trapper, likening yourself to a slaver is a low. He ups the nihilistic bravado further on “I Serve The Base,” sneering, “Tried to make me a pop star and they made a monster.” The line is superb mythmaking, turning his fall from grace into a villainous reinvention, but there’s some underlying bluster there. Future wanted to be a pop star, and he was quite good at it. “Turn On The Lights,” “I Be U,” and “Body Party,” which he co-wrote, are as essential to his discography as “Same Damn Time” or “Sh!t.” As thrilling as it is to hear Future the Monster thrash about, it’s hard to overlook the tacit death in his rebirth.

The more revealing line from “I Serve The Base,” which sounds like a goat being ritually sacrificed inside a subwoofer, is “I gave up on my conscience, gotta live with it.” That resignation lies at the heart of his transformation from man to monster and is the crux of DS2. Life without a conscience is strange and hallucinogenic. The shooters are kids who play with choppers instead of toys. God blesses all the trap niggas, but they’re still in the trap. There’s blood on the money, but Future can’t stop counting it. Future’s no moralist, so there’s no shame or abjection in this music like what you might find on a Kendrick or Danny Brown record. But there is a melancholy, maybe even a grief, in the clear disconnect between what Future knows he should feel and what he actually feels. Highs and lows all smear into a dizzy nullity, ice and codeine melting together.

The production, spearheaded by Metro and Southside, leans into that disorientation. Future’s willingness and ability to rap over anything enables them to get kooky. The TRU-inspired “Freak Hoe” headfakes as a twerk anthem but is a synth laser show. The basslines on “Stick Talk” and “Real Sisters” drop out in odd places, then thunder back in like the Lex Luger beats on Flockavelli. And multiple tracks feature the Kill Bill sirens that 808 Mafia popularized around that time, which add odd kicks to Future’s tumbling flows. At a time when trap was deeply associated with turning up, DS2 emphasizes atmosphere and color.

One of the subtlest aspects of the production is that it’s propulsive. Rap inspired by lean tends to sway, slur, and stretch to channel the way the drug slows time and perception, but these songs palpitate. The hi-hats flutter and tick. The synths and pianos surge and bop. The wooziness mostly comes from Future’s shifting flows, which seep into the beat on “Blood On The Money” and sputter into the pocket on “Colossal.” For Future, lean is more dulling than sedative: The parties may suck, but they still feel adrenal, sweaty.

DS2 ended up being an inflection point for Future. He’d go on to become a full-fledged star soon afterward, collaborating with Taylor Swift, Burna Boy, and FKA twigs outside of rap and just about anybody with any chart presence inside the genre, most notably Drake. He’d become especially important to younger rappers like Lil Uzi Vert, Lucki, and Playboi Carti, who’d take cues from his constant manipulation of his voice (and also his misogyny, to keep it a buck). It’s hard to imagine any of that happening without DS2. The album doesn’t fully capture Future’s talent — namely, it forgoes his deep-rooted love of R&B — but it distills his restless style to its pained essence.

“I come from pain, so you gonna hear it in my music. No matter how far I go, I still can never forget when I used to sleep on the floor at my grandma’s house,” he once said. A lot of rappers would dramatize those memories, flipping them into narratives about the temperature of the floor, the layout of the house, the dreams they had. There’s nothing wrong with that, but Future’s more intent to sublimate these experiences into his tones and cadences rather than his words. DS2 is the sound of all his self-loathing, all his rage, all his contempt, being poured up — and pissed out.