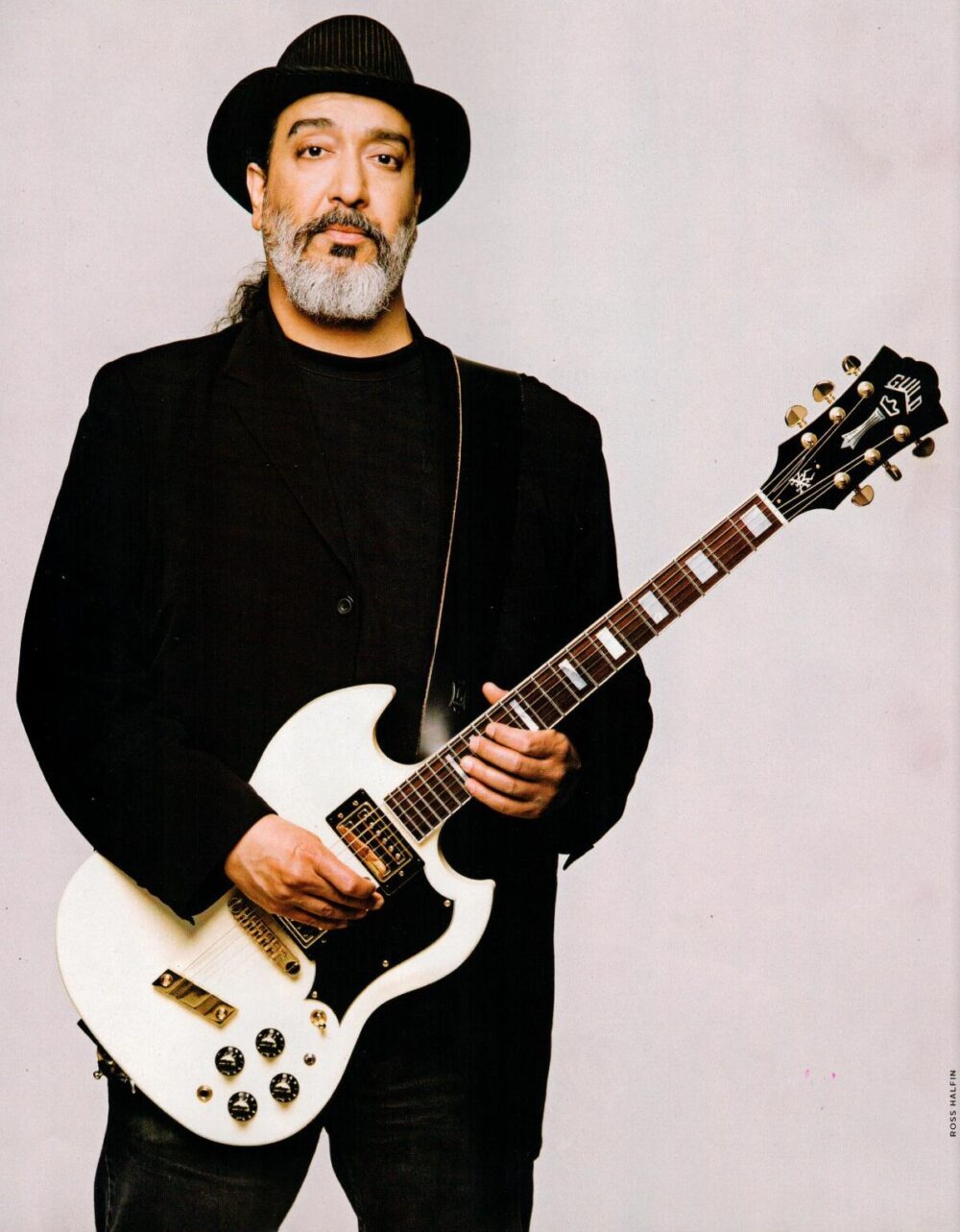

We’ve Got A File On You: Kim Thayil

We’ve Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

Kim Thayil rules. Not only is he one of history’s greatest rock guitarists, having spent decades writing mind-bending riffs and solos for Soundgarden that expertly complemented Chris Cornell’s preternatural roar. He’s also one of the best interviews in music.

Thirteen years into their eligibility, Soundgarden will finally, deservedly be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame next month, which occasioned my recent phone call with Thayil. He was thoughtful and expressive about what the honor means to him and how his perspective on the Rock Hall has changed over the years. Then, he proved willing to open up about all kinds of other subjects as we hopped around his career, from his pre-fame bands growing up in Chicago to the No WTO Combo with Krist Novoselic and Jello Biafra in Seattle to making his emotionally charged return to Detroit as part of the MC5’s 50th anniversary tour.

It was a fantastic chat, and you can read it below.

Soundgarden’s Induction Into Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame (2025)

Have there been any unexpected ripple effects from getting into the Rock Hall? Like people who contacted you that you didn’t expect to hear from, or anything crazy that’s happened?

KIM THAYIL: I think there are a few relatives who I’m regularly in contact with, but it’s been a while. But they almost immediately, the day of the announcement, said, “Hey, do you have a favorite cousin that you’d like to take with you?” Yeah, I did get a lot of congratulations, which started — the congratulations were tempered with an estimate of my sentiments. There are a few people who thought, “You know, Kim may not give a shit about this, so I’m gonna congratulate him, but I’m gonna be a little bit hesitant about how much I should congratulate him.”

There’s an aspect of [the Rock Hall] that’s very anti-indie, punk rock culture, and that’s anti-indie metal culture. In the ’80s it was not something that was on our radar at all. Even in the ’90s, it’s not where we come from. We didn’t follow who was being inducted into the Hall. It didn’t really represent us as fans. You hear about a band you really like getting inducted, and you think, “Alright, cool.” But then that was about the extent of it. So I think there might have been more cynicism and ridicule from the audience and scene that we would associate with.

So over the years, as you get older and you have new other experiences with the audience and your audience grows, you have other experiences with the music industry, you start tempering that sort of hostility — or maybe even an arrogance — you might have, that would help you to define yourself and your scene and your subculture. And you kind of loosen up on that over time. And I anticipated some of that happening. I mean, no one can ever fully understand how we’ll transform, but we all know that people do change as they get older. We started having associates and peers and colleagues getting inducted. You start learning what it means to them and what it means to their fans, and that changes your perspective.

It’s not as far away as learning that the Rolling Stones were inducted. It’s like, “Oh, I don’t think I’ve met those guys.” It’s some of my friends. Of course, many of my friends have different levels of experience within their careers, so there’s some that right away would text or email or call congratulations. There are others like, “I’m not sure how you feel about this, but congratulations,” and you just hear the shrug in their voice, in their tone, maybe because they punctuate with question marks.

And then did you come back to them with like, “Actually, I’m pretty excited about this”?

THAYIL: I would just say, “Yeah, you know, it’s cool.” And I said I think I learned from Chris’ participation inducting Heart. He learned how important it was to the fans, and that changed his understanding. He said, “The fans believe in you.” And just like, growing up, I might have a strong identity, maybe with the Beatles or KISS — or as a college-aged guy or late teens, it would have been the MC5 and the Ramones and the Stooges — and you kind of identify with that. You champion that. Because in championing a band that you’re a fan of, in a way you’re kind of affirming yourself and part of your identity and your choices, aesthetically and socially. And Chris confirmed that that’s exactly it. It’s important to the fans, as it would be to you to hear that the MC5 were inducted or something. And he said what kind of changed it for him was to see the enthusiasm and pride that someone that they believed in — and whose work was either moving or inspiring or a soundtrack to their various rites of passage — for them to achieve that kind of accolade, I think, reflected on the affection they had for that particular artist. And so that gave me a different perspective. I thought, “Yes, but these are reasons why I should perhaps respect that.” It is to recognize the fans’ allegiance.

Are you still planning to perform?

THAYIL: Yeah, I think so. We’ve been invited to do so, so that is a thing.

Do you have ideas about who’s gonna sing? I know you’ve had Brandi Carlile and Shana Shepherd at various points.

THAYIL: We have our ideas, and the familiarity and comfort we have as musicians obviously is paramount to the kind of people we would ask to play with. There are external participants who will give their input. One of them is the Hall. The Hall has some thoughts because it is their show. So we might brainstorm some people. We might think of someone from our roots in our underground, and then the Hall Of Fame might think, “Well, I don’t know if our audience will know who that person is,” so we kind of temper it, given that it’s their show. But mainly within the context of it being our performance, our musical partnerships.

So we’re going to work with people that we’re familiar with, and whose work we like and who enjoy our work. So that’ll include people we’ve recorded with before and people whose bands we’ve toured with before. And that entirely has been our focus because we think that’s the right thing to do, to share with our colleagues that we have a history with. And of course, if you know anything to the contrary, then I might be suspicious. I feel that way about any band I was a fan of that’s playing. It’s like, “Why are they playing with that person?” you know? “What’s the connection there?”

Pre-Fame Bands Bozo And The Pinheads & Identity Crisis

You were talking about when you’re growing up and define yourself by the bands that you support and align yourself with. I actually wanted to ask you about your earliest band experiences. I know as a teen you had a punk band called Bozo And The Pinheads. Was that your first band?

THAYIL: Yes, it was. I had written some songs when I was 16. And I was just kind of playing my guitar, playing for friends by myself. And then when I was 17, as a senior, I was in a progressive alternative program at school. My classmates included Bruce Pavitt, the founder of Sub Pop, and Hiro Yamamoto. Hiro actually came in the year after I graduated, but of course Hiro, co-founder of Soundgarden — a number of other people that still figure in our lives today in one way or another, They put together an end of year performance for people who are involved in performing arts, and that would be everything from the girl who sings musicals while accompanied on piano and then the people who play their folk songs on a ukulele or mandolin.

This would have been in 1978. I had the material in ’77, which is pretty much when punk rock came out. The Ramones had an album, I think, in ’76. Of course there was the Stooges and the MC5 before that. I just immediately took to punk rock. It was everything about — certainly my alienation that you might feel as a teenager, certainly my anger expressed to the outside world. And it matched my musical acumen at the time. I only knew a handful of chords, and the punk rock I only wrote songs to a handful. So it was a perfect match that I happened to be 16 and then 17, and punk rock comes out right when I’m learning guitar. The timing, what was happening in the culture, what was happening in terms of my coming of age, both socially and musically and artistically — it was pretty amazing that I would have the opportunity to hear this kind of music right when I’m learning guitar. So it was a no-brainer to go around and ask friends, “Hey man, I want to do a punk rock band. You guys wanna play in my punk rock band?”

And my friends, guys who played drums and guys who played guitar better than I did, they weren’t interested in playing any Sex Pistol songs or Ramones songs because they’re into Utopia or the Grateful Dead or the Allman Brothers, or maybe or they’re into Zeppelin. They’re into things that perhaps were a little bit more challenging or of their ability. And I was like, “Yeah, it’d be really great. I got a bunch of songs we can just throw this together quick, and we can practice.” No one had really been in a band before. Everyone had jammed with friends but not really had the standard rock lineup of guitar, bass, drums, and vocals. And so we tried it out.

The guy we got to sing, Dan Snyder, who went by Dangerous Dan, was this guy, long hair, really popular. He was a smart guy, but he’s also kind of a rebel and kind of a longhair sort of hippie. Very knowledgeable about politics and current events and couldn’t sing worth a lick, but he had that confidence and swagger. Like, for some reason girls like this guy a lot. And he was respected because of his coolness and his attitude. So he said he would do it. He could not sing, but he could stand there in front for an audience.

Do you think the music you did for that band still holds up?

THAYIL: I’ve got some old demos and tapes of our rehearsals, and I’m pretty surprised. I wrote half the lyrics and thought I was a pretty smart little 16 year old, and then Dan wrote the other half of the lyrics. It’s just surprising when I think about how we’re like 16, 17. It’s like, we were kind of smart kids, but I like these lyrics still. Every once in a while there’s a little glimmer of immaturity, but not too much. It’s kind of funny, we modeled as references the lyrics of Devo and Ramones more so than the Sex Pistols because there’s a little bit more with Devo and Ramones. The use of cultural metaphors. And it was almost hyperbolic, you know, with Devo and even Ramones. So that just kind of played naturally to our sensibilities and the kind of language we would use, how we saw the rest of the world.

It was fun. It was great. I wrote all the music, half the lyrics, and the guys all agreed to play. They did not like punk rock going into it. Like I said, they more likely listen to King Crimson or Utopia, but by the end of that talent show, we played a couple of parties. They were sloppy performances, but everyone came away from that with a new regard for it. I, of course, was getting into the Saints and the Dead Boys. Those guys, they moved from the prog rock and the hippie rock of the ’70s toward, like, Elvis Costello and the Talking Heads and Devo. I’m still in touch with some of these guys, and their musical tastes include everything from Metallica to the Dead Kennedys. Not where you thought they would end up being. We all love Bowie. That’s one thing we have in common.

And then, you had another pre-Soundgarden band, Identity Crisis, right? My understanding is that you only released one 7″ which now goes for $200 on Discogs.

THAYIL: Yeah, that was more of a real band because we would regularly practice two or three times a week in my dad’s basement or in a John Pavitt’s bedroom. And it transformed out of a previous band called the Decibels. One of the guitarists was kicked out, so they asked if I would play. I started writing, and then the lineup changed, so we changed the name, and it became Identity Crisis. We played a few interesting gigs. We’re in the suburbs, you know, so we played maybe eight or nine shows and a couple of parties, and we never really got in to play any of the city venues.

That was frustrating because we’re underage, and you need to have, like, a work permit, and you also need to be a member of a union. This is Chicago. Chicago is quite a union town. They did have indie, all ages halls, which kind of skirted around that. They might promote a band like Bauhaus or some local art-rock bands. But most of the local Chicago punk bands, they themselves are playing venues where — it was our understanding that you had to be a member of the musicians union and you need to get work permits if you’re underage and things like that. So it’s just kind of frustrating. It’s a lot easier for us to play parties and events that we would either set up ourselves or our friends would invite us to.

The No WTO Combo With Jello Biafra, Krist Novoselic, & Gina Mainwal (1999)

That was your return to the stage after Soundgarden’s breakup. What made that seem like it was the right moment, the right context for getting back out there?

THAYIL: Well, for one, I was really excited about the opportunity to play with Jello Biafra. And there was a pretty big political protest going on in the city at the time. The World Trade Organization was having its meetings and conventions here in Seattle, so it drew people from many walks of life from around the world to come here, either participating in the convention or protesting. So you had your steelworkers union, you had political groups from all over the spectrum around, organizing marches and protests.

And of course there are always some agent provocateurs. I don’t know if they represent the state or they’re just troublemakers and see it as an opportunity to smash windows. But those fringe behaviors would occur, and that would give the police the excuse to shut everything down and make the traffic more manageable. And that of course branched out into riots. It has since been appraised and ruled a police riot, years later, after all the evidence was collected, and the events and the arrests and the injuries and the property destruction, they determined that it was a riot started by the police. But some of their aggressive tactics of beating people up, violating the constitution and limiting people’s mobility and right to assemble, and various things like that. So the opportunity to play that was kind of exciting to me.

I mean, I was eight years old during the ’68 Democratic convention in Chicago, and I would see that on the news, and I’d read about it in the newspaper, and I’d ask my dad what’s going on. You know, who are Yippies, who are the Black Panthers? And then you find out that this band that becomes your favorite band in the ’70s, the MC5, they’re the one band that apparently played the ’68 Democratic convention and the riots in Chicago when I was living in Chicago. And that, by the way, was also deemed a police riot, a cop riot, with the assaults they made on the protesters and the convergence of all these different groups from the Students for Democratic Society and and the Yippies and the Black Panthers. So there was also something exciting and romantic about that. It was scary when I was eight years old, but as I got older, I started understanding that, oh man, something was definitely happening there, and there was a happening band playing it. And I eventually got to hear some of those stories from Wayne Kramer when I played with him.

But so Krist and Jello had some connection, and Jello had contacted Krist Novoselic about getting something together for this gig, and Krist said, “Yeah, we should get Kim involved.” And then Jello said, “Right on.” So I’d met Jello a few times before. I think when I first met him, he wasn’t a big Soundgarden fan, but it didn’t matter. We were Dead Kennedys fans, and I think he eventually took to liking what we did.

But yeah, that was fun. So we had a bunch of rehearsals. And the day that we were scheduled to play initially, there was some problem. Because we were rehearsing downtown, and there’s access that was cut off. So residents could access the place, people who were working could access it, but other people couldn’t. And if there was some head-thumping going on from the cops. So the whole thing was kind of difficult logistically. And there’s something that was shut down, and Krist and Jello went to the Pioneer Square neighborhood of Seattle, and there was more of an open mic spoken word thing and Jello performed there, and I think Krist did something. But the drummer Gina Mainwal and myself, we lived outside of the downtown. Like, Krist had a condo downtown, so he could access it, and Jello was staying with them. But I lived north of the city, and Gina lived east of the city, so it was much more problematic for us to access it, and we didn’t go.

But then the next day or the day after, the show that we scheduled at the Showbox happened. We were able to get down there, and a few of my friends were able to come down. It was not well attended for a lot of reasons. People were still avoiding the traffic, and the police barricades. We were able to get in there and play, and it was recorded, and that was a lot of fun.

Joining Wayne Kramer’s All-Star Band For The MC5’s 50th Anniversary MC50 Tour (2018)

You mentioned your love for MC5 and alluded to your involvement with the whole MC50 thing. Based on what you’ve said so far, it sounds like that must have been pretty meaningful for you.

THAYIL: It’s very meaningful, in so many ways that I don’t think I can get into all of them. They had always been one of my favorite bands. And probably about 20 years ago I saw the MC5 documentary, and I came out of that thinking, “Well, they’ve probably always been in my top three, but I think they’re #1 now.” I think we can say it’s my favorite band.

And then, after 2017, the year after Chris passed, Wayne called me up. Actually, it was a few months after Chris passed. I was still very, very distraught. And I was kind of not inclined to socialize and kind of being a bit of a hermit, I suppose. Just not really dealing with phone calls or people and just — oh, goddamn it, I don’t wanna obviously give any clickbait. But I mean, I was still dealing in the wake of this devastation, and that profound sense of loss and sadness continued for years. It continued through my experience in the MC5. But it was a very bittersweet, melancholic, and healing experience.

One of the things that was present on my mind was the fact that my favorite band was out of Detroit. And they were born in Detroit. And Detroit is obviously where Soundgarden met its end. And one of the things about this tour, they called it MC50 because it was the 50th anniversary of the recording of their first album. And the goal was to tour for a couple of months in the US, culminating in a series of shows in the Detroit area on the anniversary of the recording of their first album. So I’m not sure if the other guys in the band were aware of that or picked up on it, but over the course of the tour, they came to learn that, holy shit, the geographic destination of this tour is Detroit. And it would have been the first return to Detroit since the awful… the events prior. So that was always on my mind, and something about it was — it was odd. I was anxious. But there was something poetic about it. It was just very unusual, just for those things to kind of come together. It’s like, “I am heading to Detroit for the purposes of celebrating a band born in Detroit, and that’s where my band, you know… went away.

And the guys in the band were all such great people. They’re smart. Their interests were about politics and art and cultural movements, and they’re all curious. They all have great senses of humor. They’re funny, and they’re smart. They’re curious about everything. They’re people who get up in the morning before a show and they go for a walk and go check out a museum, you know, find some cafe or go to a bookstore. It was just cool. The atmosphere, both intellectually and artistically, was far different from being in a band that’s playing arenas.

It was just a different vibe. You know, Brendan [Canty] from Fugazi and Billy [Gould] from Faith No More. I mean, I’ve known Billy since the ’80s. Soundgarden and Faith No More played shows together in the mid ’80s, and he’s just always been such a great guy. And the same thing, kind of curious. And a lot of reading on that bus. A lot of people reading. I’m thinking, “This is great.” And Wayne too. Wayne was a great big brother/father figure, you know? He had a lot of experiences, from his years in prison to his years in the MC5, and he imparted this kind of wisdom. And he was a good guy — politically, socially. He was very much an advocate for the rights of minorities and women and gays and everything. He had a sense of fairness and a sense of justice and equality and the participation of all people in American society. And that was the vibe of that whole tour. And I got to go play “Kick Out The Jams, Motherfuckers” every night. It was, it was the coolest fucking thing. I think my favorite song to play, besides “Kick Out The Jams,” was probably “Call Me Animal.” It’s just, “This is a lot of fun.”

The Deep Six Compilation, An Early Grunge Landmark (1986)

Nowadays people think of Deep Six as this historic document — the birth of grunge, or whatever. When that was being put together, did anybody think of it as a significant development, or was it just kind of like another record, another comp?

THAYIL: No, we knew that as a document it was significant. We didn’t know what would happen. We knew that all of our bands were ascending, that we were some more popular bands in the Seattle indie and punk rock music scene, and we were getting bigger at that time. The U-Men were the biggest draw, but Green River started to draw up quite a bit, and then Soundgarden ended up being bigger than all of them, playing local clubs and venues and just drawing 5-600 people. That was a big deal for a local band. We would outdraw national acts.

National acts would would come, college kind of bands you might see in the college airplay or rotation, they’d come and play some theater. And Soundgarden or Green River or Mother Love Bone or someone would open up, and then once they were done, people would go outside and get a beer and go somewhere else. We were out-drawing the national band. So you knew something’s happening when people were coming to see the local band that hasn’t played in a month or two, and the opportunity to see them is a $15 ticket for some band that’s coming up from California.

So we knew that was happening at the time of Deep Six. We knew that it was documenting a scene that we saw as ours, and we knew that there was something unique about it. We knew that a lot of these bands came out of more of a punk, indie, sort of post-punk milieu and ethos, and that we were embracing elements of classic rock and metal and goth and psychedelia — just basically, the things that we thought were cool about various genres. Like, “Yeah, we’re punk rock, but why can’t we play this metal song?” Cause this is what’s cool about Black Sabbath. This is what’s cool about that new young band Metallica that’s coming out. Or this is what’s cool about Bauhaus, or this is what’s great about Pylon or the B-52s.

There were so many different kinds of genres and subgenres, and there’s something very tribal about the indie underground, where people define themselves in terms of what they’re not. And that tends to happen all the time. Young people do that as part of their identity. “I am not mom and dad. I am not the other assholes at school. I’m not the jerks at my something club. I’m this guy, and I’m about this music and this culture and this politic and not that.” Well, we all came with that kind of attitude to say, “But why not like this? I like that part of my record collection. I like this record that the guy in Green River loaned me. I like this song that the Melvins are doing.” So that’s what we all started doing. And it was kind of trippy because we knew that these particular six bands were probably the bigger bands that were representative of what was going on amongst us. And so that’s the significance of that. We didn’t know that it’d be a cornerstone or a launching pad, perhaps, for these bands’ careers. What we saw it as was a document that described what we thought was going on. Do you remember a magazine called Maximumrocknroll?

Yeah.

THAYIL: So there’s primarily hardcore, and there were a couple of writers and editors there that would advance vegan culture and stuff like that. But they would have scene reports from various states and cities. One issue might have a scene report from Davenport, and then Sacramento or whatever. And periodically there’d be a scene report from Seattle, and at least on one or maybe two or three occasions, the scene report was submitted by Mark Arm.

So, say Mark in his scene report, he referred to the Melvins. He referred to Soundgarden. And what Deep Six was, was an audio scene report, basically. It’s like, “This is what’s going on, this is our thing.” And we knew that if you went to New York, you’d hear Sonic Youth and Live Skull and the Swans, this kind of more dissonant sort of mid-tempo stuff. And if you went to Chicago, you’d get this kind of arty post-punk stuff with Scratch Acid, Big Black. And in LA you’d get this progressive post-hardcore that would have some really cool guitar noodling from the Meat Puppets or Minutemen or Black Flag. And then here in Seattle, we had this punk attitude that kind of slowed down, it was trying to be a little bit more of a — something that was maybe more inclined to make your head spin and mind trip out. That’s I think where we were coming from is, like, heavy but kind of psychedelic, kind of dark and but also kind of fun.

Soundgarden Wins Two Grammys (1995)

Were you there for the ceremony?

THAYIL: Yeah, we were. You can probably find it online, but we actually went up to accept the award. They had asked us to perform “Black Hole Sun,” and the record label really wanted us to do it. And we weren’t sure that we were gonna win. I didn’t want to do it. I said, “There’s gonna be a billion people around the world who are gonna see this. Do we want the first thing for them to see is this sort of more mellow power ballad-y type song like ‘Black Hole Sun,’ or do we want to have them see us play ‘Outshined’ or ‘Jesus Christ Pose’ or ‘Spoonman’ or something?” I really wanted to do a rock song.

I like “Spoonman.” You won for that too. “Spoonman” won Best Metal Performance, and “Black Hole Sun” won Best Hard Rock Performance.

THAYIL: Yep yep. So I kind of want to do “Spoonman,” and the push was for us to do “Black Hole Sun.” It’s like, for our fan base, they’ll like it, but there’ll be a billion people who’ll say, “Oh, this band Soundgarden, which sounds like they might have synthesizers in their band…” If you’re over on the other end of the world, it’s like, “Oh, Soundgarden, so pretty.” You do “Black Hole Sun,” like, “This is really pretty.” And then the guitar solo comes up. It’s like, “What are they doing to that pretty song?” Our name, Soundgarden, got us booked with some hippie band that did have synthesizers in Maine, like the first time we played Maine. I believe it was Portland. It was like, “What? Where are we?”

We were playing, it was kind of a restaurant, and they had a loft area — like the stairs, and you could go up in the loft, like people sat there. It was kind of a restaurant. The band we were opening up for had keyboards. And I said, “I know what happened.” They saw that Soundgarden was on tour, and they’re on some college playlist. The promoter here thought, “Soundgarden, they’re probably going to play something kind of psychedelic, and there’s probably a keyboardist in the band or something.” And we go out there, we play our heavy shit, and no one liked it. People just kind of went outside, milled around, and, and they sat at the table kind of looking at us and then we got done and the other band played and everyone came in and enjoyed their dinner and danced or whatever, but I realized that’s the kind of thing that’s going to happen.

We were booked for a college dance in Seattle, with a band called the Beat Pagodas, and they’re a fine band, but they played sort of dance new wave and I know that we got that book, probably the name Soundgarden. The college students probably thought, “Oh, let’s have them open up.” And we come out and do “Incessant Mace” and “Beyond The Wheel.”

So that’s the thing, doing the Grammys. Here’s this band that’s nominated, Soundgarden, and we come out and do “Black Hole Sun.” I thought, this is not an accurate depiction of the kind of band we are. What if we do “Spoonman” or “Outshined” or something like that? And the pressure came from the Academy and from the record label to do “Black Hole Sun.” Like, I don’t think the first time people in China hear us that it should be something more representative.

So we didn’t do it, but they got the Rollins Band to play. And Rollins Band came out and played the song “Liar,” which was also nominated. And they played live, and then they had our category, and we won the category. So I think in my acceptance speech, I said, “Wow man, Rollins Band just came out here and kicked your ass, and then you guys lied to them.” But that was — yeah, it was also a weird experience. I think part of my acceptance speech, I said, “This will make my mom and dad really happy.”

You know, my parents were probably more enthused about it than I was. Because, again, we didn’t come out of that scene, and it was the early ’90s. But my mom watches the Grammy Awards and the Tony Awards. So this is something that would put us on their radar and the radar of our family and of their friends. So their friends would call and say, “Hey, your son just won this award, congratulations.” And yeah, that makes sense to them. My friends would say, “How do you feel about your Grammy? Don’t expect me to buy you any beers now.”

The Many “Black Hole Sun” Covers

Well, “Black Hole Sun” might not be totally representative, but certainly it has made the rounds. When I was 11, seeing the video, that was my first exposure to Soundgarden.

THAYIL: It’s amazing that Chris wrote that thing from top to bottom. The only other contribution, really, was some of Ben’s bass lines, and I guess the guitar solo was the only other thing added. But it was pretty amazing. Chris wrote a lot of good songs, and certainly some that were radio friendly, but “Black Hole Sun,” it was cool for a lot of reasons. Not just because of the pretty chords, but because of the dynamic of the song and how it grows. Again, at that time being a hard rock band with punk rock and metal roots, you just thought, “Well why can’t we do something punk rock and metal, let everyone know who we are?” Otherwise the takeaway is gonna be, “Soundgarden, how pretty.”

It’s been covered by a lot of people, a very diverse range of artists. Kelly Clarkson, Paul Anka, Norah Jones, D’Angelo, Brandi Carlile, King Princess…

THAYIL: And we played with her live. At a Brandi Carlile concert, Matt and Ben and I came out and did two songs with her, two Soundgarden songs. And she released that EP, A Rooster Says, where she sang “Searching With My Good Eye Closed” and “Black Hole Sun,” and we were the backing band.

Do you have a favorite “Black Hole Sun” cover? Or is there one that really stood out to you or shocked you?

THAYIL: I didn’t know that Kelly Clarkson did it.

I think that was one of the ones on her talk show where she’ll like perform a song every day on the show.

THAYIL: I saw Norah Jones’ version, which is also beautiful because it’s on piano. I saw Coldplay perform it. Coldplay invited us down to a show in Seattle. We went to check it out, and He did a shout out to some local bands like Nirvana and Mud Honey and Soundgarden, and they played “Black Hole Sun” on piano. And again, both Coldplay and Norah Jones’ versions with piano accompaniment, it’s that kind of perspective that I always imagined to have. When Chris played it, showed us that song, it was like, those chords at the beginning are piano chords. Those chords come from the right side of the keyboard. And what impressed me at the time was, “You did that on a guitar, and this totally is a — these are total piano chords.” So it’s great to hear that. And of course, Brandi’s version is a little bit more rock, with the guitars and the drums. Coldplay and Norah’s versions are more piano-oriented, so that’s kind of cool too.