Last time he checked, he was the man on these streets. He used to hit the kitchen lights — cockroaches everywhere. He hits the kitchen lights now — marble floors everywhere. Once upon a time, he used to grind all night with that residue that was iPod white. He’s tryna get Boston George and Diego money and stack it all up like it’s Lego money. He’s emotional; he hugs the block. You ain’t never seen them pies; he’s talking so much white it’ll hurt your eyes. He really lived it, man, counting so much paper it’ll hurt your hands.

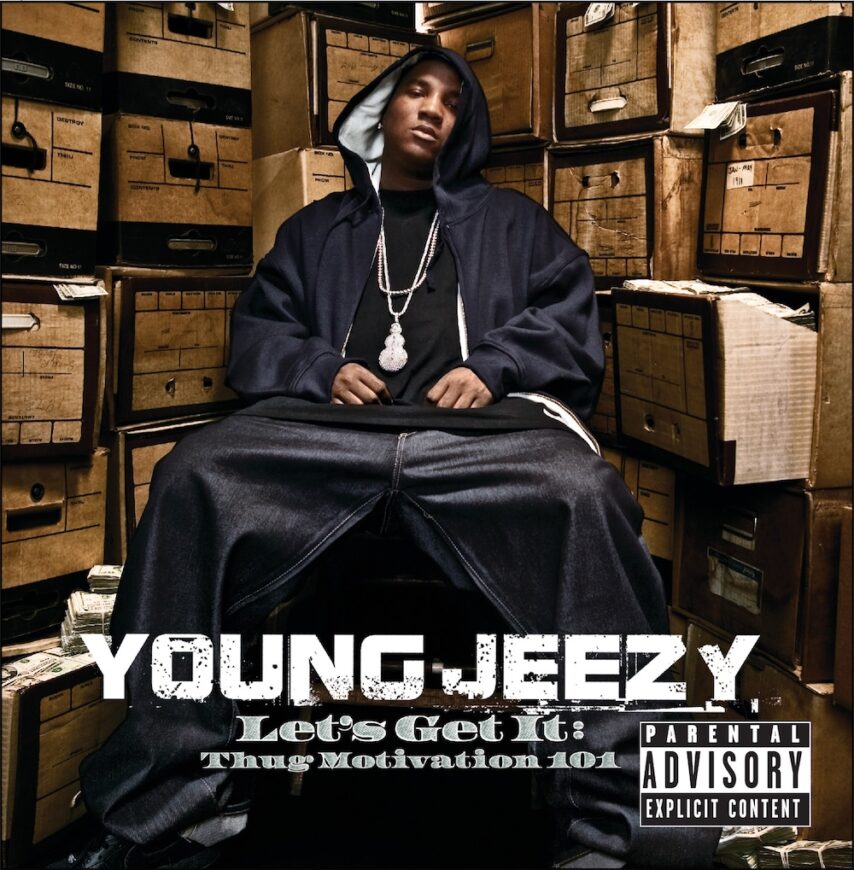

Young Jeezy claimed to be your favorite rapper’s favorite rapper and your favorite trapper’s favorite trapper. Early in his career, though, he persistently faced the charge that he couldn’t rap — that he played a shallow drug-dealer caricature and dispensed with the rich world-building, storytelling, and wordplay that his peers loved so much. But 20 years after the release of Let’s Get It: Thug Motivation 101, plenty of his lines continue to echo down through generations. If you can come up with a line that sticks with people for decades, then that’s iconography. That’s what great rapping is.

Speaking of iconography: The Snowman shirt. He looked angry, that Snowman. In the summer of 2005, Young Jeezy’s logo glared out from thousands upon thousands of T-shirts — most of them bootlegged, most of them long enough to dangle near the knees of the wearer. I had one. My brother got it for me, maybe for my birthday, I forget. On mine, the Snowman was orange glitter. Schools banned the snowman shirts because of their obvious drug-dealing connotations, and TV news shows put together disapproving video packages, which only made the logo more popular. You couldn’t ban the Snowman. The idea came from a line that Jeezy spit on Gucci Mane’s hit “Icy”: “In my hood, they call me Jeezy The Snowman/ You get it? Jeezy The Snowman/ I’m iced out, plus I got snow, man.” We got it. Def Jam started printing the Snowman shirts as a promotional stunt, something to wear in videos, but the logo quickly transcended its origins. It might’ve even transcended Young Jeezy himself, briefly becoming a cultural signifier for all things street-level disreputable.

Almost overnight, that Snowman logo seemed to be everywhere. It was an easy visual representation for a style, a sound, that had been building underground for years. With his 2003 hit Trap Muzik, T.I. codified and named Atlanta trap, the grandiose slow-crawl form of street-rap that grew out of crunk and eventually worked its way into the fabric of popular music. But even more than Trap Muzik, Jeezy’s Let’s Get It: Thug Motivation 101, which celebrates its 20th anniversary Saturday, made this criminal culture feel like the stuff of blockbuster entertainment. Jeezy wasn’t the only rap star to come out of the Atlanta mixtape scene at that time, but he figured out how to take something local and homegrown and make it resonate everywhere. In Jeezy’s hands, traditional rap virtues — sophistication, dexterity, perspective — became all but obsolete. He said shit that you could feel deep in your chest, even if you’d never seen them pies.

Young Jeezy sounded like a superhero, and he had his origin story. Jay Jenkins was born in Columbia, North Carolina, and he spent his childhood moving through the towns all around Atlanta. He never wanted to be a rapper. Instead, Jeezy fashioned himself as a street figure, a corner kingpin. Details on Jeezy’s early life are sketchy, but he had some vaguely defined connection to BMF, the Detroit drug crew who set up shop in Atlanta and flooded the city with money. They were the guys who would throw parties where they’d have lions and tigers in cages inside the club. BMF had their own rap label, led by a guy named Bleu Davinci, but he never crossed over. In his own time in the street, Jeezy watched former criminal figures like Master P clean their money up and become rap moguls, and he wanted to do something like that himself — to become a behind-the-scenes rap figure, not a rapper himself. He started his label Corporate Thugz Entertainment as a young man, but he had more presence and charisma than any of the rappers under his wing.

In his book Rap Capital, Joe Coscarelli tells the story of how future Atlanta rap kingmaker Coach K, who was just starting out his management career, convinced the 21-year-old Jeezy that he had the juice to become a real artist. That process took time. In the early ’00s, Jeezy released a couple of independent records under the name Lil J. These were strictly regional records, but Jeezy was able to get Lil Jon on a track as early as 2001. Bit by bit, Jeezy figured out his sound. Working with untested young producers Shawty Redd and Drumma Boy, Jeezy leaned hard into his raspy drawl, doubling up his voice and charging his basic, deliberate slow-flow delivery with larger-than-life ad-libs — “yyyyyeeeeah,” “ha-haaaaa!” Building on the example that 50 Cent set in New York, Jeezy put out a couple of street-level mixtapes that landed harder than the actual albums he’d already released. In 2004, Jeezy became the first rapper ever to pay DJ Drama to host a mixtape; Drama got $1,000 for yelling triumphantly all over Jeezy’s Tha Streets Iz Watchin. Six months later came that Trap Or Die, the realest shit he ever wrote.

You will still find people who will tell you that Trap Or Die, the mixtape that Young Jeezy and DJ Drama released at the top of 2005, is better than any of his actual albums. They have a point. A bunch of the best songs from Let’s Get It were on Trap Or Die first, and the tape represents the simplest, most direct form of Jeezy — the one without even the slightest hint of commercial compromise. Jeezy’s voice booms over the swollen, dramatic production with gravelly authority, and he describes his street exploits with real gravitas. Without a label behind him, Jeezy already sounded like a titan. The Jeezy of Trap Or Die doesn’t sound like a rapper on the rise. He sounds like one who’s already arrived.

In lots of ways, he already had. While Trap Or Die was still reverberating, Jeezy rapped on Atlanta mixtape peer Gucci Mane’s “Icy,” a full-blown Atlanta anthem that launched a bitter rivalry. When Jeezy landed his Def Jam deal, he wanted “Icy” for himself, and Gucci wouldn’t license it. A bitter feud erupted, and it led to Gucci killing the Jeezy affiliate Pookie Loc and evading prosecution by claiming self-defense. In the darkest way possible, that story became instant legend. It didn’t end until many years later, when Jeezy and Gucci finally did a tense pandemic-era Verzuz battle together. During the beef, Jeezy signed a one-album deal with Diddy’s nascent Bad Boy South imprint and temporarily joined his Atlanta street-rap supergroup Boyz N Da Hood. That group’s self-titled album came out just a month before Let’s Get It, and the world already understood that Jeezy was their resident superstar who wouldn’t be around for long. That LP felt like a coming-attractions trailer.

Let’s Get It leaked months before its release, and Jeezy and his associates went on the warpath, beating up bootleggers and taking their wares. In a Complex story about the making of Let’s Get It, Jeezy talks about how he was embarrassed about the leak, since its experiments didn’t present him the way that he wanted to be heard. The Don Cannon-produced “Go Crazy” beat, with its regal horns and timpani rolls, was more of an East Coast record than Jeezy wanted to make. The sleek Akon collab “Soul Survivor” was something that Jeezy didn’t understand: “I thought ‘Soul Survivor’ was going to end my career… I always associated that with being commercial.” He didn’t even like Mannie Fresh’s “boom boom clap” chant on lead single “And Then What.” He thought it sounded corny. Naturally, all three of those songs blew the fuck up.

Two decades later, the amazing thing about Let’s Get It is how true the album stays to Jeezy’s vision, compromises and all. That wasn’t how major-label rap records sounded in 2005. For the most part, big albums felt like A&R-driven patchworks, every track an attempt to appeal to a different hypothetical audience. The same guests and producers appeared on every record, a landscape crammed with sleek and expensive Scott Storch club beats. But Jeezy worked with his guys and with the Southern street-rappers — T.I., Young Buck, Trick Daddy, Bun B — who shared his sensibility. This wasn’t party music, and it wasn’t for the radio. It was epic, dangerous street music. When Let’s Get It came out, I knew jeezy from Boyz N Da Hood, his verse on Trick Daddy’s “Fuckin’ Around,” and a few stray tracks from Southern Smoke mixtapes. I wasn’t ready for the gothic sweep of the production. Just by giving Jeezy a major-label mastering job, taking away the DJ drops and the corroded fidelity of second-generation CD-burner mixtapes, it made Jeezy sound like he was stepping off an IMAX screen.

Jeezy made the world come to him. A little while after the release of Let’s Get It, the decision to include an East Coast-sounding track paid off in a huge way. Jay-Z, who’d supposedly retired from rap and who’d just accepted a new post as Def Jam president, rapped on a “Go Crazy” remix. At that point, it felt like a huge event whenever Jay did anything, and Jeezy was suddenly all over New York radio. (Fat Joe was on that remix, too. Nobody remembers that part now. His verse was good, too. Today, Jay-Z is on the streaming version of “Go Crazy,” as if he’d always been part of the song.) “Soul Survivor,” the Akon collab that Jeezy thought would ruin his career, became a full-on crossover hit. Now, it’s a track that my kids know, a soundtrack to a TikTok trend that they have unsuccessfully tried to explain to me.

About a month after Let’s Get It came out, I moved to New York and got a job blogging for the Village Voice — my first gig writing about music full-time. On my first day in the office, I got an email offer to interview Young Jeezy, and I thought it must be a mistake. I still think it was a mistake, but I took advantage. My second day on the job, I walked into a Def Jam conference room and got an audience with the Snowman. He played the character. My interview has been lost to internet history, but the thing I remember the most was the way Jeezy talked about rap as a vocation: “I ain’t a rapper; I’m a motivational speaker. I don’t do shows; I do seminars. I really talk to people.” It was a line, an angle, but there was something to it. When I listened to Let’s Get It, I felt bulletproof, impervious. My life experience was nothing like what Jeezy described in his music. The monumental force of it still spoke to me anyway.

Ever since Let’s Get It, Jeezy has mostly made variations on that sound over and over, to diminishing returns. Plenty of his other records have been great, but none of them have been as great as that. He never moved on from that sound, and he’s still the same guy, with or without the “Young” in his name. Jeezy immediately spawned a million imitators. When Rick Ross first ascended to stardom, it felt like Def Jam’s attempt to manufacture another Jeezy. Since that time,. Jeezy’s sound has become more and more widespread, to the point that trap drum patterns are inescapable across virtually every genre of global popular music today. But I can’t think of many trap records that have hit with that record’s thunderous impact. It’s a rare, beautiful thing when a rap album comes out and immediately reshapes the entire landscape. Let’s Get It is one of those records. The Snowman remains unbanned.