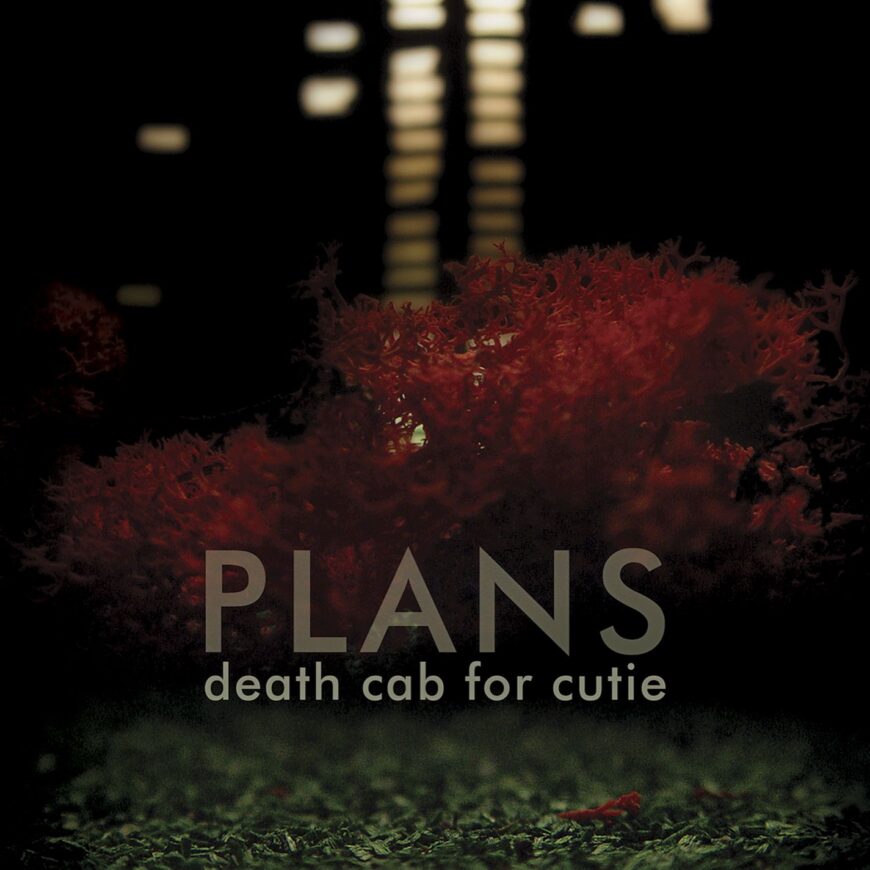

Someone asked me if I was going to discuss Plans positively or negatively for this retrospective — the album, Death Cab For Cutie’s first for a major label, turns 20 this Saturday — but the discussion of whether Plans has aged poorly or not is trite at this point in its life. I answered, “Both, probably.”

Death Cab were likely my first favorite band and one I don’t think I’ll ever get away from, but Plans suffers more than most of their pre-2010 albums when it first crosses my mind. I’m a staunch Narrow Stairs truther, listen to The Photo Album more than any other Death Cab For Cutie album, and went to the Transatlanticism 20th anniversary tour. Plans is harder. Maybe that’s the memory of middle school I put onto it, or maybe it’s osmosis from the cultural analysis that has deemed it Not That Good. Or maybe it’s because the first album review I ever read was for Plans, not glowing and already several years old by the time I decided I had to find out how to process music that felt so much bigger than the pop punk I’d spent so much of my early life listening to thanks to my older sisters.

Plans came after 2003’s one-two punch of Death Cab’s Transatlanticism and Give Up by Gibbard’s other band, the Postal Service – both albums that seem to be only further galvanized by nostalgia and remain in good standing among even those who find themselves more as ex-fans. For Plans, though, the memories of more vulnerable, emotional younger years seem to act as more of a sopping wet blanket fostering mold over even the more undeniable tracks. Memory can be fickle like that. I’ve been guilty of throwing only the more embarrassing of my associations with Plans over the whole album – “I Will Follow You Into The Dark” middle school Facebook statuses on a good day, melodramatic “So Who’s Gonna Watch You Die?” middle school Facebook statuses on the bad ones.

The difference in Death Cab’s cultural relevance between their 2003 and 2005 albums – and the jump from the independent label Barsuk to the major Atlantic – was mostly irrelevant to me when I was listening to the albums as a middle school kid in 2008. The O.C. wasn’t a cultural touchstone for me – Adam Brody was merely Dave Rygalski, who I wasn’t aware disappeared from Gilmore Girls to take on his role as Seth Cohen, but his character’s presence was felt by the child version of me watching the show with my mom and sisters. Death Cab For Cutie came to me first, as many songs did, through a YouTube video that featured “Title and Registration” off Transatlanticism, then the songs my dad already had downloaded in iTunes on his white iMac desktop. That meant mainly Plans – it’s still the Death Cab album he prefers, so those are the songs that lived on my mp3 players and iPods. To this day, a misspelled version of “Brothers On A Hotel Bed” is on my phone – “Bed” swapped for “Bus” thanks to, I imagine, a YouTube rip that came from someone trying to avoid the video getting taken down.

When I actually turn the record on, though, I’m taken back to being 11 years old laying in the dark in my twin bed letting “Marching Bands Of Manhattan” take over my body, starting from my chest, until it just about chokes me. I’m 13 standing behind the baseline on a volleyball court, mumbling lines from “What Sarah Said,” waiting for the referee to blow the whistle so I could serve – a ritual I’d repeat until I quit playing late in high school. I’m 14 getting a text from my dad during school asking if Death Cab and the Postal Service have the same singer. I’m 15 on my way to a dentist appointment finding out Ben Gibbard got divorced from Zooey Deschanel. I’m 16 sitting in my dad’s car, driving past the Kohl’s and Target in the town I grew up in, looking at the album art on his XM radio while he turns up “Crooked Teeth.”

Debate half-empty…

Looking at the album with 20 years of music after it, it’s easy to see how the cracks made by Ben Gibbard’s worst lyrical tendencies would become ravines on later albums.The low moments on Plans are mostly down to the starts of those cracks. “Summer Skin” reads a little bit too saccharine and indulgent with one of his most awkward lyrics in “And I knew your heart, I couldn’t win.” The extended house metaphor laced through “Your Heart Is An Empty Room” doesn’t feel all that successful, and the subject matter – an inability to feel satisfied where you’re at with the person you’re with – is better tackled by Gibbard himself over no fewer than a half dozen other songs, including nearly all of the entire Open Door EP.

“Someday You Will Be Loved,” with a near satisfying build in its final minute, eventually claws itself toward the part of my brain that can find no faults with anything Chris Walla has ever produced, but it’s one of few songs where the vocal performance fails the band by suffocating the music. An even more repetitive track, “Different Names For The Same Thing,” succeeds where “Someday You Will Be Loved” falls apart. There is energy and urgency that is allowed to build in the higher contrast of the front and back halves of “Different Names.” It’s not just a swell, it’s a rush delivered alongside the best bass line of the album – a consistent highlight of the album, even on songs that fail in other ways. “Someday You Will Be Loved” can never quite escape lackluster lyricism and lethargic plodding, but even that one achieves a great bass performance.

…or half-full.

The opener is almost always the best song on a Death Cab album. It’s a thesis. Even when the albums have disappointed me, the opener never does. The tension of “Marching Bands Of Manhattan” is the tension of the record – it’s a build of anxiety and optimism and sorrow and comfort and inevitability. Chris Walla is making music to fill a big room, but you can’t get away from Ben Gibbard’s voice, always front and center, no matter how much sound is pouring in around him. The magic of Death Cab, for me, has always come down to the play between Walla’s huge scope and Gibbard’s intimacy.

There is endless building and collapsing over the course of the album, but I think it ultimately finds balance. “Crooked Teeth” yields a moment of brightness (and a more successful house-building metaphor) in its true guitar solo and big harmonies. “Soul Meets Body” sees Ben Gibbard doing more of a talk-sing than usual. It’s the furthest away he sounds on the whole album, almost hazy behind jangly guitars and percussion, and the song is better for it.

I can’t help but feel positively about “What Sarah Said” despite it dipping into the melodrama that I so associate with being a depressive 12 years old. Sometimes 12-year-old me was right. The song is a hospital at night – stark and full of the hum of anxiety. The piano, a repeating riff for much of the runtime, quietly drives along underneath until fizzling out after everything else falls away, is in direct contrast with the piano of “Brothers On A Hotel Bed.” The former is never quite peaceful. It’s omnipresent and creeping like the machines that beeped through the night when I slept on the tiny couch next to my sister’s bed after she had open heart surgery. The latter is warm – more a glow around Ben’s voice as he comes to terms with a different sort of end rather than something stalking behind him.

“I Will Follow You Into The Dark” suffers under the weight of similarly over-playlisted love songs of the era – Bright Eyes’ “First Day Of My Life” comes to mind – but I struggle to find fault in its straightforward acoustic approach. I’m charmed by the clarity and simplicity at the center of the record. It remains, for me, one of the best love songs of this century, and I think there’s a great deal of practical truth in it – men typically don’t live long after their wives die. That can be a romantic notion instead of a reflection of something wrong with heterosexuality, if you want it to be.

Death permeates much of the album. It’s a collection of songs about planning for endings, somewhat fitting and predictable for a work released a few weeks after its lyricist’s 29th birthday — a birthday the same day as mine, making Plans an album created while Ben Gibbard was the same age I am now. The perspective of the album, the tug of war of never being satisfied with not wanting to end up alone, settled itself in my bones when I was a preteen, but I feel its anxiety nagging now more than ever. Even if Plans feels like the start of issues I’d eventually have with the band, it’s balanced by the feeling of the uncertainty lodging itself further into my chest. The more I try to take it on its own terms instead of as a record I loved when I was first learning to love music at all, the more I find the comfort in the sound.

I’m 23 driving across the country in a moving van finding out my dad and I have the same favorite Death Cab song. I’m 24 dealing with a breakup by letting side 3 of the double LP sit on my turntable. I’m 25, I’m 26, I’m 27 arguing with my friends on a podcast about what there is to find in Ben Gibbard’s writing as an adult. I’m 28 laying in the dark in my one bedroom apartment with my eyes closed letting “Marching Bands Of Manhattan” choke me.