Any diehard Springsteen fan can tell you all about the counter-narratives.

Everyone knows the peak run, the streak of one iconic Bruce Springsteen release after another from mid-’70s to late ’80s. Those weren’t just classic albums but installments in a world Springsteen was building — chapters in a novel as much as individual records. During those years, he wrote and recorded a lot more than he released, but he narrowed things down to the absolute best work, the work that told the story he wanted to tell about himself and the American experience. Then, in 1998, he released a box set called Tracks that colored in all the parts of that story that had before taken place offscreen.

In the eyes of many fans, Tracks became as hallowed as the albums themselves. There was, somehow, a bounty of incredible B-sides and unreleased material, enough for whole other albums in between the ones we’d already known for decades. It was his first vault release, but not the last. Archival expansions of Darkness On The Edge Of Town and The River showed more paths not taken.

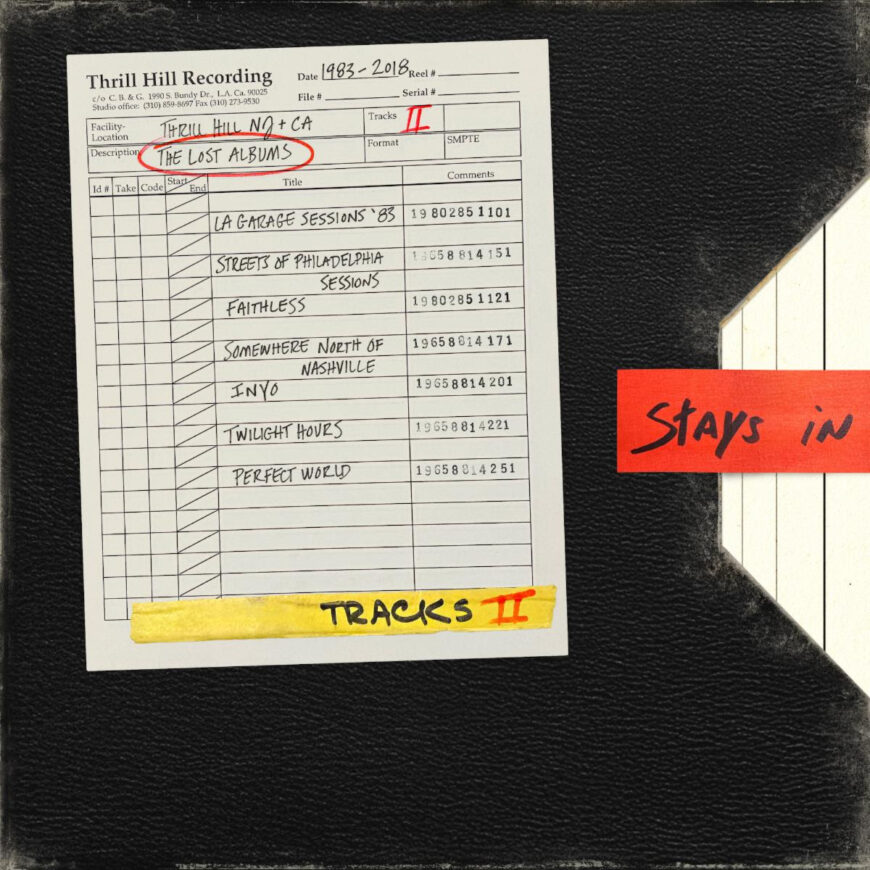

A few months ago, Springsteen finally announced the long-suspected, heavily anticipated second installment of Tracks. For some time, fans had clamored, knowing there was still plenty of unreleased material collecting dust. But Tracks II is different from its predecessor. These aren’t lost songs that could’ve comprised albums, but actual albums that had remained on the shelf, played only for Springsteen’s family and friends. Depending on how you look at it (we’ll get into this more in a bit), Tracks II features seven new Springsteen albums, totaling 83 tracks spanning 1983 to the ’10s. Some of these releases had been rumored or theorized; others were completely unknown. The whole premise is daunting: How does this guy still have so much music we haven’t heard?

In some introductory writing accompanying the box set, a direct line is drawn back to 1982’s Nebraska, the album of haunting 4-Track demos Springsteen decided to release as-is after abandoning an attempt at recreating it with the full E Street Band. Nebraska’s indie cred and lo-fi influence are long since established, but it also functions as a pivotal turning point in how Springsteen thought of writing and recording. As Tracks II presents it, the holed-up, solo creation kicked something open in Springsteen’s head. Over the years, he’d develop more sophisticated methods at home studios, but the practice was the same: Now he could experiment and iterate at home, constantly and on his own rhythm, and he ended up with vast amounts of music that didn’t make it out into the world.

As Springsteen readily acknowledges, the big counter-narrative of Tracks II is a more complicated ’90s than the conventional understanding of his career suggests. From the outside, these have often seemed less productive, wandering years: Springsteen out West in LA, starting a family. In 1992 he released two symbiotic rock albums, Human Touch and Lucky Town, neither of them his strongest. To some tuneless and to some a masterpiece, the sparse The Ghost Of Tom Joad followed in 1995 before, finally, Springsteen reconvened the E Street Band at the end of the decade and mounted a mainstream comeback that would cement his status in the 21st century.

Tracks II features several albums that could’ve come out in those days and would’ve significantly complicated the story, instead depicting Springsteen’s ’90s as a restless, experimental one — trying out new genres on the other side of the mega-stardom bestowed upon him with Born In The U.S.A. in the mid-’80s. From there, the collection also features complete surprises and albums Springsteen has discussed for some time.

Even for the devout, Tracks II is overwhelming. There is a a lot of information revealed that was previously only hinted at. These albums cast a new light on certain eras and are often intertwined with other releases, their gestation and shelving and release spanning decades. It’s far more arcane than the first Tracks. How do you contextualize and review a 40-odd year data dump of mostly finished projects that would equate a different artists’ entire discography? Here is an (Extremely) Premature Evaluation, broken down by album, trying to make sense of the newly fleshed-out story of Bruce Springsteen’s latter-day career.

LA Garage Sessions ’83 (1983)

RIYL: Born In The U.S.A., Nebraska

Canon Contenders: “The Klansman,” “Unsatisfied Heart,” “One Love”

To kick things off, this isn’t exactly a “lost album,” but another glimpse of what Born In The U.S.A. could’ve been. The LA Garage Sessions is a long grab-bag of recordings — some of which we’ve heard other versions of, some of which we haven’t — in no real album arc sequencing. At the same time, it’s some of the most exciting material included on Tracks II.

Following Nebraska, Springsteen set up a home recording station during a temporary early ’80s stint in Los Angeles. Amidst the Darkness and River expansions, fans have long awaited a similar treatment for Born In The U.S.A. — one that would presumably include the legendary full-band Nebraska recordings as well as these demos, which often circulated as a bootleg (sometimes called Unsatisfied Heart) online. Because of those leaks, some of us have known about these songs for ages, and already know they are vital additions to the Born In The U.S.A.-era outtakes already featured on the first Tracks.

To everyone else, this is essential listening. Just as on the original Tracks, the LA Garage Sessions showcase the insanely prolific and inspired stretch between Nebraska and Born In The U.S.A.. In this instance, these are less finished tracks suggesting the completely different albums BITUSA could’ve been, and more documents of a transitional time. Many songs, like “Richfield Whistle” and “John Deer,” pick up where Nebraska left off. But the most interesting stuff is when the scrappy home recording approach starts to gesture toward the big, synth-laden sound Springsteen would eventually adopt for Born In The U.S.A.. Many years ago on this very site, I once wrote that Adam Granduciel’s Springsteen fandom was as if he’d nicked the sound of these sessions — bleary, ghostly, synthy heartland rock. Just as material like contemporaries “Frankie” and “My Love Will Not Let You Down” became spoken of amidst some of Springsteen’s more famous material, there are songs here — “The Klansman,” “Unsatisfied Heart” — that tussle with the best things he’s ever released.

Streets Of Philadelphia Sessions (1994)

RIYL: “Streets Of Philadelphia,” Tunnel Of Love

Canon Contenders: “Blind Spot,” “Something In The Well,” “Waiting On The End Of The World,” “We Fell Down”

Next to Electric Nebraska, this is what everyone’s been waiting for through all the years of a rumored lost albums box set. We’ve long known about this album, though details were often scrambled. It’d be referenced as the “hip hop album,” “the relationship album,” Waiting On The End Of The World. It was the whole album of material in the vein of “Streets Of Philadelphia” and “Secret Garden,” for some reason buried despite the massive success of those tracks.

Each of the albums in Tracks II comes with an essay explaining their origins, themes, and maybe why they didn’t see the light of day way back when. As he got into the mid-’90s, Springsteen had this album ready to go. But he considered that it was a dark relationship album — exploring “matters of doubt and betrayal” — after Tunnel Of Love, Human Touch, and Lucky Town had been three relationship-oriented albums in a row. He worried that maybe this isn’t what his fans wanted, and he put it on the shelf while he temporarily reunited E Street for the recordings that ended up on 1995’s greatest hits compilation.

The Streets Of Philadelphia Sessions are both exactly what you’d expect them to sound like, and also one of the strangest prospects on Tracks II. Today, it sounds like a lost classic, but you could imagine how it may have further muddled a confusing ’90s for Springsteen. How would listeners have made sense of this then? Calling it Springsteen’s easy-listening album?

Of course, it is not that. “Secret Garden” is featured here, and you can see how all of this material spilled forward directly from the loops-and-synths experiment of “Streets Of Philadelphia.” The Philadelphia album has me thinking things I never thought I’d think about a Springsteen album. Like how the greyscale synth textures and reedy vocal melodies almost make it like a missing link between works as disparate as Tunnel Of Love and The Ghost Of Tom Joad. Or that the grain of Springsteen’s voice against atmospheric smears and gently thrumming drum programming recalls the Blue Nile’s tension between late-night lived-in humanity and alien soundscapes.

More than anything else on Tracks II, the Streets Of Philadelphia Sessions is the sort of erstwhile missing chapter that explains part of the main story. The seeming lack of productivity in the ’90s wasn’t that Springsteen wasn’t working, or that he didn’t have the muse, but that he was unsure of various genre experiments. Now, this album feels like the end of an arc begun with Tunnel Of Love, with a handful of striking ballads and songs like “Something In The Well,” where you can hear strains of a straight-up acoustic Springsteen song rendered against a hissing, festering backdrop. The synths throughout are ambient — far from the glimmering leads of his ’80s recordings. If this had come out in 1994, it may have confounded Springsteen fans. But it would’ve lived on as a touchstone for all of his artier-minded acolytes and progeny, just like Nebraska.

Somewhere North Of Nashville (1995)

RIYL: Devils & Dust, about half of Western Stars, Born In The U.S.A. outtakes from the first Tracks, We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions

Canon Contenders: “Poor Side Of Town,” “Silver Mountain,” the alternate version of “Janey Don’t You Lose Heart”

When Tracks II was first announced, the easy assumption was Somewhere North Of Nashville emerged from the same era as Western Stars, considering it shares a title with one of the latter’s best songs. Instead, Nashville is another genre experiment — a mid-’90s venture into shoot-from-the-hip country music as a sort of antidote to recording the more harrowing material for The Ghost Of Tom Joad.

In the Tracks II essays and elsewhere, Springsteen often talks about the idea that sometimes he thought he was working on one album, and two (or more) took form. Nebraska and Born In The U.S.A. are closely linked, while other Tracks II albums mingle with previously released albums: Inyo and Devils & Dust are from the same stretch of post-Joad Western writing in the back half of the ’90s, while Twilight Hours and Western Stars are sister albums. Nashville sessions took place in the afternoon and then Springsteen would go cut Joad songs at night, but aside from the idea that they kick off his Western writing, you wouldn’t necessarily guess these two albums were happening at the same time.

Rather than the desolate tales of Joad, Nashville is almost more reminiscent of 2006’s We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions. Meaning: This is a loose, often more-competent-than-it-should-be genre exercise that occasionally teeters on cosplay. Most of the uptempo jams, like “Repo Man” or “Detail Man,” could’ve made a lot of sense in the hands of ’90s country stars if Springsteen had sold them off. Here, they are a sort of throwaway hootenanny — fun, but more curios than crucial additions to the Springsteen catalogue. The “country” label is also sometimes a stretch. Aside from gorgeous pedal steel courtesy of Marty Rifkin (then fresh off Tom Petty’s Wildflowers), some tracks sound like standard Springsteen solo songwriting, or the rockabilly-tinged B-sides from the Born In The U.S.A. era — evidenced by the re-recording of “Stand On It.” (There’s also a wistful reimagining of the same era’s “Janey Don’t You Lose Heart” here.) The best, and likely most durable material, arrives in the ballads and laments: “Poor Side Of Town,” “Silver Mountain,” “You’re Gonna Miss Me When I’m Gone.” It’s a bit easier to understand why this one remained hidden, but even with mixed results it’s another interesting counterpoint to the pre-established story of Springsteen’s ’90s.

Inyo (Second half of the ’90s, 2010)

RIYL: Devils & Dust, The Ghost Of Tom Joad

Canon Contenders: “Adelita,” “One False Move,” “When I Build My Beautiful House”

Like The Ghost Of Tom Joad, Devils & Dust, and Western Stars before it, Inyo is one of Springsteen’s Western albums — either directly inspired by his time living in California and traveling the Southwest, or reflecting back on it. In this instance, Inyo took influence from long drives Springsteen took through Inyo Country on his way to Yosemite or Death Valley. Since much of it was written and recorded at the same time as Devils & Dust — most of which was done in the ’90s despite being released in 2005 — you can easily look at this as Devils & Dust: Part Two. If you are, like me, one of the fans who considers Devils & Dust one of the great underrated/unfairly memory-holed Springsteen albums, this is a good thing. It also means Inyo is less immediate or revelatory than the rest of Tracks II. On initial listens, the Mariachi swoons of “Adelina” and “The Lost Charro” jump out. Yet just as his other albums of border story songs, it seems like reflective, spare material like “One False Move” or closer “When I Build My Beautiful House” will become the most enduring.

Faithless (2005-2006)

RIYL: Devils & Dust, stray atmospheric Springsteen tracks like “Paradise,” gospel-tinged ’00s tracks like “My City Of Ruins”

Canon Contenders: “Where You Going Where You From,” “All Gods Children,” “Goin’ To California,” “My Master’s Hand”

Faithless is an outlier in the collection, originally conceived as music for a film that was never made. Springsteen has referenced it as a “spiritual Western,” and, fittingly enough, Faithless exists in the Western strain of his writing but is just a touch stranger — incantatory and celestial rather than featuring the gritty of-the-earth stories often populating these albums. There isn’t anything else quite like it in Springsteen’s catalogue, but it isn’t jarring either. Primarily completed in a window between touring for Devils & Dust and recording for the Seeger Sessions, it feels like the final word on this sort of material for Tracks II. A major thread in the collection is that this roots/Americana/Western material could often feel like occasional subplots in the mainline albums, but with the addition of Nashville, Inyo, and Faithless, it’s clear how profound this other voice and viewpoint became for Springsteen.

And in the instance of Faithless, this results in a small, powerful album. “All God’s Children” is a guttural Tom Waits blues-gospel howl. “Goin’ To California” and “Where You Going Where You From” are both earworm ruminations tinged with gospel and aided by backing choirs. Though faith and salvation are obviously themes elsewhere in Springsteen’s work, there feels as if there’s something different, more metaphysical, afoot here. It’s not the lost album that’s going to deliver instant endorphins, but it feels like it will have the reputation of being something very special and personal in Springsteen’s work the longer it’s around.

Twilight Hours (Early ’10s)

RIYL: Western Stars, Working On A Dream

Canon Contenders: “Sunday Love,” “Late In The Evening,” “High Sierra”

In the late ’10s, Springsteen began talking about a solo album he had been working on before Wrecking Ball, a collection of “Southern California pop” influenced by Glen Campbell, Jimmy Webb, and Burt Bacharach. Part of this ended up being Western Stars, and Twilight Hours is the other half. There are times when I’ve wondered if this should’ve been the one that got released first.

“Sunday Love,” holy shit. Springsteen’s remarked that part of the experiment here was more complex chordal structures than he’d usually include, and the flow of the music and melody in “Sunday Love” alone are jaw-dropping on first listen. It almost feels like a backhanded compliment to compare this to Working On A Dream, but there was some precedent there. Springsteen had already, at times, flirted with abandoning the seaside bar songs of the Jersey boardwalk for the lens-flare Pacific and Beach Boys music boxes. Here, he delved fully into that syrup-y croon only occasionally utilized before. He’s belting over sweeping strings, pristine pianos, and cinematic arrangements.

Though it was inspired by California pop, Twilight Hours is more abstract and placeless than many of the other lost albums. Appropriately for an album called Twilight Hours, it is occasionally noir-ish, built for lovelorn solo meanders through cityscapes anywhere in the country. The essay about Twilight Hours describes songs full of longing, romantic loss, brokenness. It’s all rendered with a beauty and precision that is, frankly, shocking for an album deemed unfit for release.

Given, Springsteen said he held this one back because he felt the aesthetic would be a bit too much, would “throw people off.” Now Western Stars exists as some kind of preparation, but only partially. That album still made sense in the lineage established by the Western albums. Twilight Hours feels like a different beast. And, look, maybe you’re reading this now and are incredibly skeptical regarding me gushing about Springsteen’s mid-century fantasia. I was skeptical, too. But along with Streets Of Philadelphia, Twilight Hours is an experiment that immediately announces itself as a transfixing missing piece in Springsteen’s story.

Perfect World (Mid-’90s, Early ’00s, Early ’10s)

RIYL: The Rising, Wrecking Ball, High Hopes

Canon Contenders: “Blind Man,” “Rain In The River,” “If I Could Be Your Lover,” “Perfect World”

Perfect World was not a pre-existing album, but one Springsteen concocted for Tracks II, pulling together songs that span the ’90s and ’00s. While it’s a valiant and moderately effective attempt at compiling an album-esque experience, it inevitably feels akin to High Hopes’ hodgepodge of eras and styles crashed together. Mostly, that’s because it opens with three ’90s tracks Springsteen wrote with Joe Grushecky; the first of them, “I’m Not Sleeping,” is a convincing revival of prime E Street anthemics. Another rocker, “Rain In The River,” was the lead single for Tracks II and remains an oddity even with the context of the lost albums. It’s a visceral, haggard standalone from the mid-’90s, not quite like anything he’d done before, and only hinting at some of the directions to come.

That’s what becomes interesting about Perfect World. Because of the time it traverses, it almost becomes an album-as-document of Springsteen making his way back to a full-throated rock sound, developing his late-era iteration that would carry him through the 21st century. That being said, the album also has plenty of ballads and moodier material, a handful of which are instant classics — the elliptical amble of “Blind Man” is mesmerizing, and the title track is a weathered bit of optimism to close out a collection that has its fair share of darker, heavier work from Springsteen. Along with “Rain In The River,” “If I Could Be Your Lover” is both unusual and a highlight. It’s a smoldering, sinuous piece of music that was considered for Wrecking Ball.

Compared to some of the other lost albums, Perfect World is inevitably minor — rather than expose a previously secret left turn, it collects some strays you could easily imagine on any of Springsteen’s ’00s and ’10s rock albums. Those strays, though less exploratory than their peers on the other lost albums, are often excellent.

That’s one takeaway from parsing all the new music on Tracks II. These are all solo albums, often pushing the limits of Springsteen’s sound and songwriting mechanics, often showing us zigs and zags we never knew he took. In the 21st century, Springsteen rocketed back to popularity and a near-bulletproof level of reverence. He partially did it by making music that, for an aging rockstar, was uniquely relevant and strong. What you see across Tracks II is that even in his self-editing, he wasn’t hiding music that was inferior. His ear and eye are often as incisive in these weird mutations as they are in the sounds we more readily associate with him. We knew he was malleable, but not quite this malleable.

We also knew that, between Tracks and further archival releases, the peak era was mostly mined. There can’t be much more music waiting from the ’70s and ’80s. While a collection of B-sides and lost songs might inherently seem like something for obsessive fans, the first Tracks offered a whole lot more of the things most Springsteen fans already loved — more Darkness On The Edge Of Town, more The River, more Born In The U.S.A.. The kind of thing you always wish for from a cherished album but rarely exists to the extent that Tracks did.

So this time around, Tracks really is for the diehards. Do most Springsteen listeners really care about having their minds changed on the ’90s, or the other music he had cooking during the already-busy stretch between The Rising and High Hopes? Maybe not. But if you have followed him through the decades, and come to appreciate the strengths of his later work, Tracks II offers material that clarifies and occasionally betters it all. There are things here that may become crucial Springsteen reference points, and many that won’t. There are at least a few dozen songs where I can’t believe they haven’t been in my life all along. Once more, if you follow Springsteen down the rabbit hole of his counter-narratives, there are songs that feel like old friends but that you can claim as you own, without all the history of Born To Run or Born In The U.S.A.. It’s hard to believe he still had this much material of this quality waiting in the wings. It feels like a gift to finally hear it all.

Tracks II: The Lost Albums is out 6/27 via Columbia.