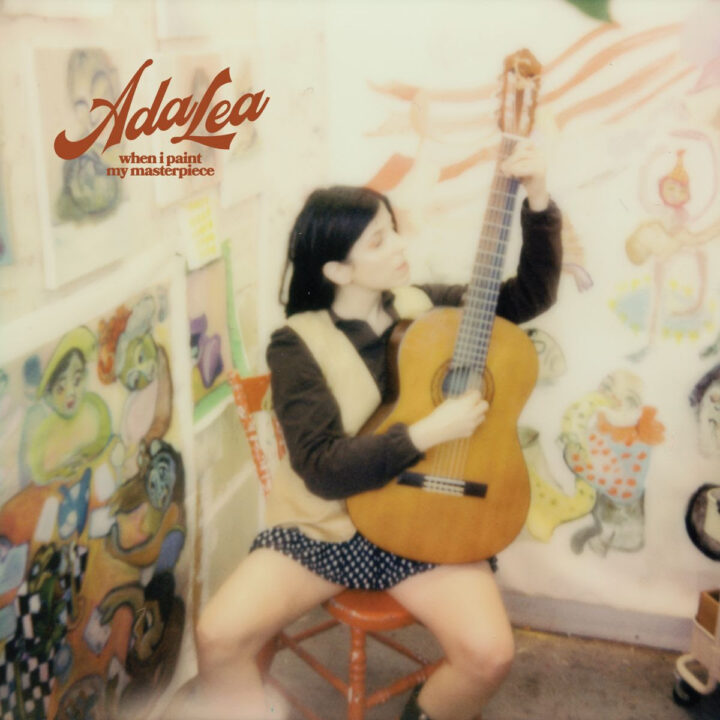

Ada Lea Is Living On Her Own Terms

Alexandra Levy

Montreal's Alexandra Levy on her fantastic new album, sharing a recent trauma with the world, her figure skating past, and more

You have to live some life to write like Alexandra Levy. Some musicians come out with a new album because it’s been a few years since the last one, but the songs on when i paint my masterpiece — the multi-disciplinary artist’s new album as Ada Lea, out today — seem to have emerged out of necessity. The album strikes a difficult balance in that it feels like an outpouring of Levy’s heart and soul but is also carefully considered at every turn. Not that it’s a perfectionist project; the music is pleasingly loose and shaggy, and Levy sings like a real human being rather than a cursive-voiced machine. But you can tell how much thought went into the lyrics, the arrangements, the sequencing.

The years since 2021’s one hand on the steering wheel the other sewing a garden have been full of trials both personal and professional. In the face of those challenges, Levy planted herself at home in Montreal: working a day job, writing and revising, finding peace through community and support groups. Perhaps as a result, when i paint my masterpiece is an album with a real sense of place, its songs full of items and locations and weather patterns amidst Levy’s keen observations.

On tracks like the spindly and propulsive “something in the wind,” she finds new ways to convey universal ideas, like the constant tension between the necessity and impossibility of love. Sometimes she makes me break out in joyous laughter, as on “moon blossom,” when she sings, with all her might, “I dropped my hat/ And you’d never guess how it’s lying, or where it’s at!” The humor is subtler when she seems to be toying with the classics, pump-faking a “Hallelujah” reference on “i want it all” or threading a very “Here Comes The Sun” guitar part into a song called “everything under the sun.” On that note, “bob dylan’s 115h haircut” begins with a bold, celebratory proclamation: “Bob Dylan couldn’t have written this song/ Not even if he wanted to, not even just for fun.” She’s so right.

Beyond the wise and winsome words, there’s a varied topography to the music itself. Levy and Here We Go Magic’s Luke Temple produced the album, jumbling full-band recordings together with solo performances. From track to track, it toggles from guitar to piano, from stripped down to fleshed out, from folksy to rocking to vintage swooning pop. It seems to be in conversation with everyone from the Band, Margo Guryan, and Joni Mitchell to modern-day peers like Big Thief and Natalie Prass. The more I listen to it, the more I love it.

I recently jumped on a call with Levy to discuss when i paint my masterpiece and some of the life events that informed it. Below, stream the full album and read excerpts from our conversation.

It sounds like the past few years have been hard in some ways. Do you feel like you’ve moved past some of that, or do you feel like you’re still right in the middle of it?

ADA LEA: No, I’m feeling pretty good these days. It’s been discouraging trying to find how my music can fit into the music landscape at this moment. Since I started releasing music, I’ve just found touring to be really difficult. It just feels like a system that’s maybe not set up for me. But over the years, learning about my needs, now I feel more comfortable asking for help when I need it or just feeling like I’m more in control of my surroundings. So I’m feeling good about that and feeling excited about having finished the album, and for the album to come out, and for everyone to hear it.

It’s a beautiful album.

ADA LEA: But I’m feeling good. I’m feeling excited. I mean, after a while of not touring, you start to want to tour again.

I’ve read that you made a choice to break away from the rhythms of the music industry and plant yourself in community for a while. What informed that decision, and are you happy with that choice?

ADA LEA: After so much touring in 2021 and 2022, I kind of took a step back and recentered. It came from canceling some shows at the end of 2022 and not wanting to reschedule them, and I guess also conversations with my manager at the time. I don’t want to paint him in a in a bad light or anything, but I think it does speak to the industry at large — we’re all kind of scrambling, and it is a really difficult place for people to invest their their time and energy or to justify the amount of time and energy that others are spending. So he dropped me after I canceled the shows, and after I had told him that I wanted to stay put for a while, and then my agent also did that. And it kind of forced me to reset in a way.

What made you decide that you didn’t want to reschedule the shows? Was it just that you felt like you needed a break? You felt like the tour touring thing was too grueling?

ADA LEA: Yeah, I had a medical emergency, and I wasn’t able to physically do the shows. And then, after so much touring and also asking, “Well, what are these shows for?” Like, “I just went to these cities. What’s the plan here?” They put it — it makes sense in quote-unquote business terms, but I don’t think it was considering my needs at the time. It was just like, “We want to see how many tickets you can sell in this city, and that’ll help determine for the next cycle.” I was like, I don’t feel good right now, and I actually like I’m too tired to do these shows and if it’s just, If we’re just kind of gauging how many tickets I’m worth like that, I don’t want to participate.

I don’t know how much of this album you had started writing before you made that decision, but it feels like an album that is situated in a place. You’ve done some surreal videos and whatnot, and I want to talk about those. But the songs themselves, for the most part, they’re very situated in the real world. There’s weather and seasons, and you talk about specific items and locations. And so even though you’re wrestling with these very deep universal questions about love and breakups and what it means to fail or succeed as a person, they’re playing out in these very realistic scenes. I feel like I’m hearing a person like living their life in a place. Do you make it a point to put those kinds of grounding details into the songs? I’m thinking of the mini-fridge being traded for box springs and sunglasses on “baby blue frigidaire mini fridge.” You’re building a whole place within the song.

ADA LEA: Well, when you’re working with surrealist imagery, you are taking images from the everyday and you’re creating a new function for them. So I do think that it’s good. I think it feels well-placed in the everyday. Because I also love reading magic realism, and then I don’t really like to hear it that much in songs. A song for me needs to feel more grounded. And there can be aspects of it that are brought in — and I like to see it visually too, the magic realism and the occult and stuff. So I’m glad that it does feel grounded in a place, because for me personally, I can’t connect to songs that don’t feel grounded in that way. But then also taking the images and creating new meanings with them, like with the combinations being more associative and coming from a place of instinct over rational.

One thing I appreciate about your new album is how many different textures and styles you cover from song to song. It’s not one of those albums where everything blurs together. I appreciate how you are fleshing the songs out in all these different ways, or not fleshing them out at all. Were you aiming to have an eclectic album, or was this something where the song sort of tells you what it needs, arrangement wise, style wise?

ADA LEA: The way I approached it was I had the songs that I had recorded at Port William Sound in Ontario with the band, live in the room. And altogether, I would just kind of place the songs in an order, and then I was just going by feel of what my ear was wanting and craving. And I often felt my ears becoming tired and needing a change. So that’s when I scheduled one more day in January of this year and recorded some new songs. And I knew that I just wanted them to sound different. And we got someone else to mix them and stuff too, Al Carlson. I loved what he did with Jessica Pratt, and he also mixed my friend Brigitte’s album [Common Holly’s Anything glass]. That was the sound that I was wanting. And then there were two extra songs that I just recorded myself. And that’s when it started to feel good, where I had the blend of sound that I needed for my ears to feel good while listening.

When you released the “midnight magic” video, you mentioned having a miscarriage. I’m very sorry about that. How difficult was that to express publicly? Or is that the kind of thing where it’s so intrinsic to your personal experience that it would have been harder to keep it to yourself?

ADA LEA: Yeah, I felt like it would have been harder to keep it to myself. And I do think that my next album will be about it completely. Because it was a termination for medical reasons, which is kind of not spoken about but affects so many families. And especially now what’s going on in the States, it’s so difficult for women to get the care that they need when something turns up. I had an amnio and stuff, but there are findings in a later stage of the pregnancy that shows the baby either probably won’t make it to term, or there will be physical — yeah, there’s a lot. There’s sometimes a gray diagnosis too, and you’re not really sure exactly what the baby has, but it’s showing signs that the systems are not forming the way that they should be. And some people are willing to take that risk and to follow the pregnancy all the way through, and some people are not, and it’s the choice of every woman to decide that for herself and not like the state deciding when’s a good time to terminate it.

So I think, yeah, my next album will be about that specifically. Because it also happened after the termination that I had nothing to engage with in art. I couldn’t find anything to read, anything to listen to, anything to watch that was describing this experience that so many people go through. There’s so much shame wrapped into it. It really intersects with so many things. There’s disability rights. It intersects with women’s reproductive rights. And also around labor — like, you can’t really get the time off that you need because it’s not really talked about. Then people don’t know how to handle it in a work environment too, and so then you don’t get the time off that you actually need.

But luckily there were lots of support groups, and I feel like I’ve made it through to the other side. I’m grateful to be in Quebec. I can’t imagine having to go through something so physically overwhelming and emotionally overwhelming and also have to travel, to take a plane to another state to get the procedure. This is why the tests are there — the early tests, the NIPTs or the amnios and stuff — is to give the family all the information that they need, and for them to be able to make the decision that would suit them best. And yeah, sometimes it’s a very difficult decision.

You mentioned that you couldn’t find things to watch and listen to and read that dealt with that situation. Was that music video your attempt to create some art that did engage with it?

ADA LEA: Yeah, I would say so. And it also seemed like a fun activity more than anything. It was fun to make and fun to create with my friend. I can’t say that I was trying to access that pain and such that I experienced, but it was just a fun project to think of. And I didn’t even think we would be able to pull it off. But I’d like to do more stuff like that.

On a far different subject, I wanted to ask about your other music video for “something in the wind.” You wanted to do this ice skating routine. I believe you mentioned being inspired by Nathan Fielder to do that?

ADA LEA: Yeah, I love Nathan. And I just finished watching The Curse, which was so uncomfortable. But yeah, I’m a really big fan of Nathan’s. So, I have to come clean about this, because I did figure skate as a child, and it was a big part of my life. And I just stopped skating completely 20 years ago and didn’t put on my skates — I think I put them on once. My friend Britt [Brittney Canda], we’ve been talking about this video for so long. And she kind of pushed me to — like, she found free ice time for me. She’s like, “OK, meet me at this arena,” like, “We’re gonna start to train for this video.” And I was really dragging my feet and didn’t want to do the training, and it felt like I couldn’t do it. I was not strong enough, and I didn’t feel like training, and I didn’t wanna move my body at all. And then I watched The Rehearsal, and I realized that that’s kind of what I also did. Even though I had skated as a kid, it felt like I was re-learning the sport. And he really inspired me. I mean, he is a comedian, but I find him so inspiring that he can do the bit until the very end, and he can acquire all of these skills, And I don’t think it’s that different than what anyone else is doing artistically. That’s kind of what being an artist is. You’re learning, you’re curious about something, you’re passionate about one thing. I mean, the people that I find most inspiring are the ones that take it quite far. And yeah, it was so hard to do that video that I felt like I had started from the beginning.

Why did you stop skating? Was it just that you get to be a certain age and it’s just like “I’ve had enough of this, I need to find something else to do with my life?” Or, like, “I’m not gonna be in the Olympics”?

ADA LEA: A lot of the people that I was around, that was their goal, to be in the Olympics. And my goal was always just to make the Quebec team. And the year that I qualified for the Quebec team, it ended up being the year that you would also qualify for the Canada Games. So they took, I think, the person who came first in each province, and then there was a competition. And it happens every four years, so it just was a random series of events that made it so that I would go to the Canada Games after provincials. And there was no downtime. I think that maybe I would have continued skating if I could have had more time to rest, but there wasn’t any rest period, so it was like constant training for almost a year just because of how the competitions fell in a timeline. And I just, I couldn’t. I didn’t want to do it anymore. I would get to the rink and start crying. It just really felt like I was not aligned with what my purpose in life would be, and also missing out on my youth and my childhood.

How old were you when you stopped?

ADA LEA: I was 14. So everyone was having sleepovers and doing the girl stuff, and I was, like, lifting weights and running and standing on a ball and practicing my balance. But it’s interesting ‘cause I didn’t place very well at the Canada Games, but there was this really young girl that I hadn’t ever seen before, and she placed so much higher than everyone else. And I think she ended up going to the Olympics to represent Canada.

It’s interesting, I feel like this whole experience is echoing the one that we talked about earlier with pulling the plug on touring. You seem like you are a person who has learned to have boundaries and to draw a line and say, “I’m not willing to continue this pursuit if it’s going to destroy me as a person.”

ADA LEA: Yeah, I think there are parallels between the two, definitely. It’s the same thing of feeling like, “Oh, this has become a really competitive environment.” I feel like there’s a lot of pressure. I’ve kind of lost the thread here, and I need to reevaluate. Who knows what things will end up looking like, but I do love to play music, and I love to perform, and I love to write songs, and I love to be creative. And I don’t need much in return. But there are things that I need, which are, like, I need to feel safe, and I need to not be in financial ruin after a tour, and I need maybe more financial support. And then the rest I love, so if I had those things then I think it would just be such a more enjoyable experience.

And I do think a lot of musicians are talking about this more. And now with the streaming crisis, we are trying to figure out ways that it can work. Because it’s not working as it is right now, and we’re all hoping for change. I have some solutions in mind, but I need, like, a billionaire to fund the project, but yeah, we’ll see.

Do you want to lay out your solutions now?

ADA LEA: Yeah, I can lay out my solutions. In Canada, we do already have the granting system, which has sustained me for the past like eight years. It really depends on the the year, but I would say they’ve allowed me to continue creating music and to have subsistence to live. And it’s subsidized by other work that I do, freelance work and teaching and whatever. The solution would be that there is — I think this would be a private program because it would be too risky for it to be public and to risk losing the funding, because it would need to be at least like a 10-year program to try it out.

There would be a committee, and the musician would make a proposal to the committee, and that’s already what happens with the grant system now, but it wouldn’t be project-based. It would be that you’re just given subsistence for one year, and then at the end of the year, you, there’s a review period. And they would see If you’ve managed to make anything with the funding that you received, and if you pass the review period and they deem you like a quote-unquote artist worthy of funding, that you’re like using the money well, then they would fund you for two more years. And I think it would just be like $2,000 a month Canadian. I don’t know what that is, maybe $1,500 American or something? But it would be enough to pay your bills and to continue working on your projects.

And then, after two years, it would be, I think, three years. So then in total it would be six years that you would be funded. And the goal would be that at the end of those six years, you would be able to generate enough income by yourself that you wouldn’t need the support of this group. And then you would start to pay it back to the younger generation. So it creates this cycle where you’re being supported and you’re giving into a system.

That’s interesting. You gotta get that in a PowerPoint and get in front of — I don’t know who are the most artist friendly billionaires.

ADA LEA: My friend said that’s kind of what the French system is like. Like in France, I think you just have to play a certain amount of shows, and then you get funding for the year. And it helps people record music. It helps them live a better life. They’re able to keep writing music and going on tour. You do kind of need that boost in the system.

when i paint my masterpiece is out 8/8 via Saddle Creek.