Agriculture On How Zen Buddhism, Lou Reed’s Transformer, Bob Dylan, & More Influenced New Album The Spiritual Sound

Olivia Crumm

It can be so hard to succinctly pin down what goes into the “ecstatic black metal” of Los Angeles band Agriculture that sometimes that self-proclaimed label feels incomplete. At the very least, the band itself feels that way about their most recent work. “This record is not really a black metal record,” vocalist and guitarist Dan Meyer offers as a disclaimer about The Spiritual Sound, the group’s sophomore album. Sure, there are blast beats and thundering drop-tuned riffs aplenty, but there are just as many passages where the clouds suddenly part and the entire light of a song will shift. Touchpoints that call to mind black metal or thrash or doom take up just as much real estate as the stretches that feel right in line with shoegaze or post-rock. If The Spiritual Sound can be considered “a black metal record,” it plays pretty damn loose with what a black metal record can sound like.

Hearing the band agree with that at the top of this interview raises the question: What other contradictions are at play with Agriculture? The first single for this record is called “Bodhidharma,” named after the famous Chinese monk whose teachings have reverberated across millennia, and the album bio mentions that Zen Buddhism is a big factor for Meyer’s songwriting. Vocalist and bassist Leah B. Levinson even mentions that, though the band sought to engage with “bigger questions we’re asking about spirituality and struggle” on this record, she has seen people misinterpret that Agriculture is somehow an endorsement for Christianity, as if some listeners take the hymnal appropriations of the de facto coda to “Bodhidharma” — “Hallelujah” — as uncritical affirmations of that faith. So you’ve gotta figure that Zen Buddhism should be a solid foundation by which the band carries itself, right? “I think we will truly become a Christian band,” Meyer says with a grin toward the end of our Zoom chat. Well, shit.

The truth of the matter is that Agriculture have never been a band of clean classifications, and The Spiritual Sound pushes them even further into a carefully considered eclecticism. While last year’s EP Living Is Easy switched between elated charges of riffs and folk-like incantations from song to song, the tracks of The Spiritual Sound contain entire slippery, multifaceted worlds unto themselves. It’s not uncommon to hear the record’s most frenzied songs like “My Garden” or “Flea” build up the din to a breaking point, only to suddenly pull back and reveal a more melodic core nesting beneath the chaos all along.

A prime example of this is the record’s latest single, “The Weight,” which starts as a sludge-ridden march, only to continuously shift in intensity between a beatdown-like stomp and sparer passages featuring little more than clean guitars and bass — and that’s all before the solo that sounds like a Van Halen guitar part put through an insect whine of a noise pedal. “To some extent,” Meyer elaborates, “there’s a genre agnosticism there. In calling ourselves an ‘ecstatic black metal band,’ it sometimes gets a little lost that that’s a joke. It’s silly to call yourself that. But what we’re laughing at is that you can play with genre in metal in a way that you can’t in other fields. It feels a little more expected and infinite to play around from this large pool of influences.”

That comes through in discussing the massive sprawl of influences Agriculture found themselves engaging with during the course of working on The Spiritual Sound, only a fraction of which come from the world of metal. Instead, entire parallel realms of folk, classic rock, string composers, and literary subcultures make up the bulk of what the band found themselves turning to while writing and recording the album. As the group is quick to note, it’s emblematic of how unpredictable their writing process can be: Levinson and Meyer would often bring in song ideas they came up with on their own, only for the initial kernel to get fully torn apart and pieced back together when filtered through everyone else. In other words, no single island of influence would remain so once other voices entered. “You think you’re doing something,” Meyer says of the process, “and then you see it and you’re like, ‘Oh, no, I’m actually doing something totally different.'”

Below, listen to “The Weight” and learn more about how everything from Lou Reed to free jazz shaped The Spiritual Sound. And as for Meyer’s comment about Agriculture becoming a Christian band… well, you’ll just have to read on to learn the true contradiction at play there.

Zen Buddhism

DAN MEYER: I grew up in San Francisco, and there’s a larger-than-normal footprint of Zen Buddhism there. There was kind of a Buddhist craze throughout the whole United States in the second half of the 20th century, but there was this one Japanese teacher named Shunryū Suzuki, or Suzuki Roshi, who founded a temple called the San Francisco Zen Center. It’s a really large and locally influential organization — they have three of the most beautiful properties in California, full stop. They have a monastery in the Los Padres wilderness called Tassajara that’s amazing. A lot of people would go on summer vacation there — the monks would open it up for a guest season in the summer. It becomes hospitality practice. And then there’s this beautiful center in the city, and there’s a farm in Marin that’s crazy beautiful. Everybody kind of knows about it a little bit — it had a presence. That, plus the remnants of the Beat Generation — Gary Snyder moved to the area, and The Dharma Bums and all that.

When I was thirteen, for my bar mitzvah, my mom’s girlfriend at the time gave me a copy of Suzuki Roshi’s book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, which is a really San Francisco thing to do. I read it and really liked it — it seemed really obviously true — but also I was 13, so I wasn’t that interested in it. But I always kept it. A few years later, I lived at the temple at the San Francisco Zen Center for a week, and it was really a profound experience for me. It was a lot of meditation and work practice. Zen is distinct from other forms of Buddhism, in the sense that the main practice “Zen” is just a translation of the Chinese word “Chan,” which means “meditation.” It’s a Buddhist practice that’s based almost entirely on sitting and working, so a lot of work practice goes into it. That week, I was just sitting and peeling garlic in the kitchen, and it was really profound. As I was leaving, I remember telling the teacher, “This is amazing and I think this is really important, but also, I’m 16 and I want to get drunk and have sex. I don’t want to be a monk.” And she was like, “That’s great. Go do that, go get beaten up, and then come back whenever you’re ready.”

I started practicing here at the Los Angeles Zen Center a few years ago, and I found that the teachings in the Buddha Dharma, and specifically in Zen, seem quite obvious and direct, but also really fun because they don’t make any sense. It provided a kind of vocabulary artistically, as well as spiritually, to express some of the concepts I was interested in looking at in Agriculture. There started to be a parallel in what I wanted to write and what I was practicing in my personal spiritual practice.

When you say it gave you a vocabulary artistically, what do you mean by that?

MEYER: I think a lot of it is lyrically. I think it’s pretty clear. If there’s a song about the Dharma, I wrote it. If there’s a song about the trans experience, I also wrote that. Just kidding, that one’s gonna be Leah.

KERN HAUG: From my own experience studying Buddhism in the past, it was related to learning about physics at the same time and how those things went together for drumming. My sense of interacting with the physical universe is related to the things I’ve learned about Buddhism over the years. I’ve never had an intentional practice the way Dan does, but it’s always been a casual part of my life for a long time.

Judeo-Christian Theology

It feels like the band pulls from this from time to time, like on something like “Hallelujah.” Is there something that compels you about this kind of spirituality as outsiders to it?

MEYER: The Old Testament, for sure. I’ve actually never read the New Testament. “The Well” from the first record is directly drawn from Genesis. To a certain extent, the Bible is almost like The Odyssey or Inferno. Almost everyone in the world, but certainly everybody in the West, is familiar with the Bible and the stories there. It’s kind of like a cultural ur-text, like “Twinkle Twinkle [Little Star].” [Sees Kern give a quizzical look] In the sense that no one remembers…

HAUG: [Imitating Meyer] “Like ‘Twinkle Twinkle.'”

MEYER: Like no one remembers when they heard that song for the first time, but everybody knows that tune.

HAUG: I know what you mean. I just like the example. [Laughs]

MEYER: I think it’s the same with Bible stories. I think they bang. They’re profound. I don’t know if there’s a lot of religious significance there for me, personally, but they’re quite profound and a source you can draw from that’s pretty deeply rooted. That also has to do with the fact that I went to Jewish school.

LEAH B. LEVINSON: Yeah, I’d agree with that too. I think one of the strengths of Christianity and Catholicism is the stories, and the images they provide. I think they’re incredibly powerful, especially in terms of symbols and mythology. You can retain them. This is how I relate to them in my personal life — you can retain the power of that without reinforcing or adopting the structures around it. It can be something that can be appropriated or inherited, and made personal through creative or spiritual practice.

For me, part of what made that make a bit of sense was reading more about Carl Jung and his understanding of spirituality and religion a year or two ago. Prior to that, I felt very attracted to especially Catholic imagery — the saints and all that. That, and understanding the way symbols can function in our lives, and knowing that, just because you’re drawn to something, [that] doesn’t mean you need to understand it in this wider context it comes from. It’s speaking to you as a powerful symbol of its own, and you can integrate that without taking the larger structure. Certainly, I don’t think we’re an endorsement for Christianity, like some people seem to interpret us. That’s not where we’re coming from at all.

There’s a Bible verse that’s Micah 5:15, but I wasn’t sure if that was something you were drawing from for “Micah (5:15 am)” or if that’s entirely unrelated.

LEVINSON: That actually was adapted from the poet Ted Berrigan, who I was reading when I was writing the songs. He has a poem [“Sonnet #2”] that starts, “Dear Margie, hello. It is 5:15 a.m.” I adapted that, moving it closer to the name of a friend of mine. That was really it. And then I looked it up after and found it was this Bible passage that was pretty intense.

MEYER: [Reading the passage] “And I will execute vengeance in anger and fury upon the heathen, such as they have not heard.”

LEVINSON: I read it and I was like, “Woah,” but I took that as an interesting coincidence and resonance that I would just embrace and not shy away from.

MEYER: I didn’t realize that. That connection was never made for me.

LEVINSON: I didn’t know there was a Book of Micah. [Laughs] I think I texted you guys that that was going to be the name for the track, and then I happened to Google it and was like, “Oh, what the fuck. This is heavy.” But then I read it and I was like, “That’s not not what this is about.”

Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets

LEVINSON: His book of sonnets put him on the map, and in that book, he did these collage poems where he talks about what’s going on with him and his friends, and it was on par with him clipping up newspapers and letters and putting them all next to each other. His whole thing was giving everything the proper weight — not making too much or too little of something, giving it its significance in the poem amidst every other aspect of what’s going on.

AIDS-Era Literature

LEVINSON: The reason I turned to a lot of that literature when I was in the writing process [was a desire to] see what queer people in the past were making in times of crisis that has sustained — how they produced work that speaks to the larger questions while being unambiguously queer and portraying queer lives. For myself, as an artist and performer, my presence as a queer and trans person is important. I’ve seen in my own life and in people who come to see us live that that’s important, so that’s something I want to be present in my work. At the same time, I sometimes struggle with work that stops at that, where the end goal is that sense of representation.

I was turning to certain authors and filmmakers and musicians from that era who were making work directly about huge struggles going on in their lives and communities. While we were on tour one time, I was reading Close To The Knives by David Wojnarowicz, which was one of the big influences. That’s sort of a memoir of that period. There are so many chapters that are just letters to politicians, directly calling out what they’ve done. There’s a chapter that’s just memorializing one of his lovers and creative partners who he watched die of AIDS. It’s about those things, but it’s also a book that’s unambiguously about what it means to write a memoir, and what it means to live a life with friends and lovers, and what sex means, and what artmaking means. There’s a really great essay in it that’s just about photography, and that’s it. It’s all part of the same fabric. That’s really what I was looking to in a lot of that literature: how do we talk about these things, and not just put ourselves in a box and speak to an echo chamber?

The Visual Art of David Wojnarowicz, Dennis Cooper, My Bloody Valentine, And Olivia Crumm

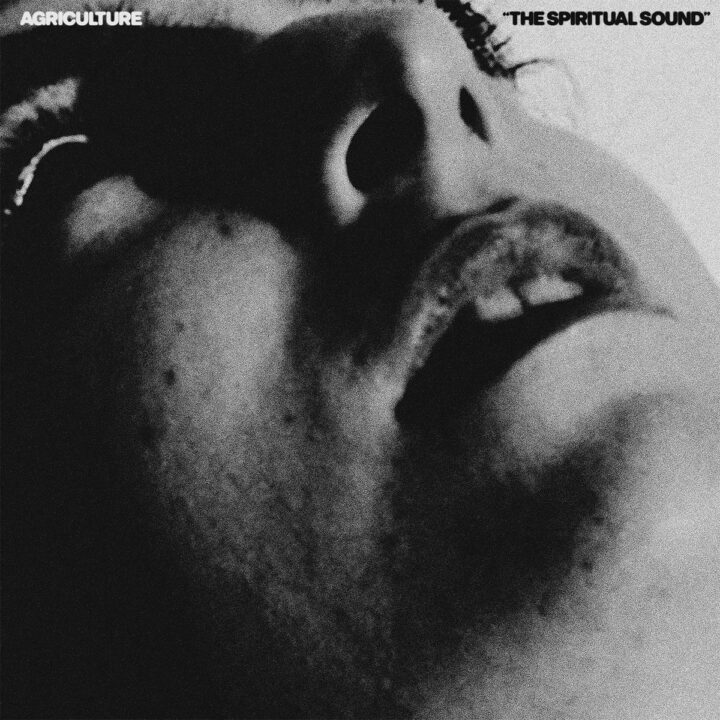

LEVINSON: David Wojnarowicz has some portrait photos — there’s the one famous one with a face poking out of the sand. That was rattling around in my brain. Another author I had been reading was Dennis Cooper, and we did some full-body portraits [with Olivia Crumm] that reminded me of the covers for the George Miles Cycle. What we ended up with for the album cover was this really tight crop of a much broader photo of me reclining on a couch. We went with the tighter close-up of the face because it abstracted a lot about the photo. When we were getting to the design and formatting of that, one of the references Dan and I pointed to was Loveless by My Bloody Valentine — this close-up to the point of abstraction. After the fact, I saw the resemblance to the cover of DJ Sprinkles’ [Midtown 120 Blues]. And I had someone mention [The Passion Of] Joan Of Arc — this face that looks like agony or pleasure, but you can’t quite tell. I think that’s something Olivia is really good at: these weird abstracted subjects.

DJ Sprinkles

I noticed you have the artwork for Midtown 120 Blues framed on the wall behind you, and I feel like that album speaks to similar themes in terms of the larger contexts of queer art and the culture it emerged from.

LEVINSON: She’s amazing for helping me think about this stuff. Her queerness or however she defines herself is so unambiguously a part of the practice, but at the same time, sometimes the records are just essays on Marxism. [Laughs] There’s something really inspiring about the command of that in Terre Thaemlitz’s work.

Eddie Van Halen, Alexi Laiho, György Ligeti, And George Crumb As Guitar Influences

RICHARD CHOWENHILL: When Dan was talking about how we’re pulling things apart and put things back together when we’re in the room together and working on something, there’s a certain organicism to it, in terms of what feels right for this part — adding a guitar melody, or putting a solo here or there. For me, a lot of it is about truth — what intuitively feels right and helps deliver what Dan and Leah say the song is about, what the music feels like to me.

If we want to talk specific guitar things, of course my playing is heavily influenced by Eddie Van Halen. He’s just so inventive, making the guitar speak in a way that can be really powerful, and gave us a lot of tools. If we’re talking about extreme metal, Alexi Laiho from Children Of Bodom is a really great player. So those are the teenage idols for me who were just so good at playing, but on the other side of it are these people I got into in my later teenage years.

The 20th century composers like George Crumb and [György] Ligeti are really important because of their string quartet writing. There’s so many interesting things with Ligeti in his second string quartet — these really crazy and interesting chromatic gestures that push toward a sort of goal at the end of the tunnel, but the gesture in and of itself becomes this musical treat you can chew on. That’s happening in the left hand, and then in the right hand, there’s the bow placement that’s either on right up on the bridge, or on the other side of the bridge, or closer to the neck. For me, that transposes very easily to the pick. These were influences that I was intuitively calling on as we were working through things.

Noise, Free Jazz, And AFI

HAUG: There’s a new Wreck And Reference single, and Ignat [Frere] is an old friend of mine. He and I had a band back in college called Knice, and that was when I went from being a finesse drummer with a lighter touch to first playing heavy music. I would bike over to his house and use his drumset, which had bigger drums that hit a lot harder. I used my drumset at my first show with that band after practicing on Ignat’s drumset, and I was like, “Oh, I need a new snare drum. This isn’t loud enough.” So I got a new snare drum, and I’ve been using that same one since 2010.

I was getting into heavy music back then and going into noise [influences] like Zach Hill and Brian Chippendale. But Tony Williams’ sense of relating to the melody in jazz was also a big thing. With Agriculture, [those influences synthesized into] this other way of playing heavy music, while following the melody a lot. I love playing blast beats — they’re almost a kind of non-beat. I always think of it as a hummingbird thing, where you’re keeping this motion going throughout.

But with [The Spiritual Sound], I kept finding myself thinking about AFI, because there were all these turnarounds. They were my first favorite band when I was 13 or 14. Leah doesn’t listen to them or really think about them at all, but the songs she brought in kept making me think of them, and she and I both share more of a punk background. I kept noticing the songs had parts that would turn around really fast — I kept needing to change the drum part really fast — versus this more continuous black metal feel. So I found myself going back and listening to AFI more, which was fun, because I hadn’t done that in a long time. It was kind of a trip. It gave me a lot of feelings, tripping out on where my mind was at as a 14-year-old.

Emma Ruth Rundle

MEYER: Emma is a homie and we love her as a person, and she’s also one of the most powerful voices that I’m aware of right now, both as a songwriter and a vocalist. When I sing clean vocals, especially in distorted textures, it’s very helpful to have someone singing with me. My voice works better with another voice, whether that’s a doubled version of my own voice or in harmony with another’s. It was a dream to be like, “I wonder if Emma would lend her unbelievably powerful voice to [‘The Reply’],” and she was super down, which was great.

Lou Reed’s Transformer

LEVINSON: It kind of snuck up on me as an influence on this album. That’s an album that really shaped me. I was maybe 13 when I first heard it, but before then, I’d listened to a lot of classic rock and heavy metal stuff, and then I got into punk and got into Transformer, probably through Iggy & The Stooges. I don’t even know if I’d really listened to the Velvet Underground before I heard Transformer, but it was an album that was pretty formative for me. It’s always been a part of my musical DNA, but I hadn’t really thought about it a lot until the past couple years, when I started revisiting it. I remember having a month or two where I was hooked on it again and hearing it in new ways. It just became an album where all these different things about its lyrics had seeped their way into my songwriting for years.

I started thinking about how Lou Reed’s songwriting — on Transformer, but also on the Velvet Underground self-titled — is almost like these nursery rhymes for gay urban adults. I would be walking my dog and have one of the songs stuck in my head, and they can almost be these little prayers or totems. They’re so simple. Like, “I’m So Free” — the whole verse is “Yes, I am mother nature’s son/ And I’m the only one/ I do what I want and I want what I see/ Huh, could only happen to me/ I’m so free.” It’s this very simple rhyme, this very simple idea about this big concept.

He also does this thing of naming characters, but not like how a lot of songs use the names of people to represent a whole idea or moment or feeling. Instead, the way Lou Reed writes about people is like they’re just these little toys or something. They aren’t fleshed out, and they only exist for a couple lines. “Walk On The Wild Side” or “Hangin’ ‘Round” are really good examples of that, where each verse is like, “Jeanie was a spoiled young brat, she thought she knew it all/ She smoked mentholated cigarettes and she had sex in the hall.” Just listing traits.

I found that really helpful with writing this album. I tried to write a lot about connection and friendship and relationships, but with that style of songwriting, I could almost take this mode that was more journalistic — naming people and things that happen. I knew I’d be screaming these lyrics, and it feels like there’s sometimes a lot of drama when you’re screaming. You’re like, “This is going to be something I’m screaming, so it has to mean a lot.” But when I took this more journalistic songwriting approach, it was like there were no feelings being suggested. It was almost more neutral and objective.

Records With Two Distinct Sides

CHOWENHILL: I’m always approaching things from a compositional perspective. I studied composition, I love music composition, and this is obviously where a lot of these contemporary classical and 20th century influences come from. I think about production in that way as well. When we’re producing the record in my studio, there comes the time when it becomes, “How does this all work together?” For me, personally, I think about how it lands in a way that works musically, if you were to think of the first note of the record to the last note. How do we connect these in a way that makes sense? What does this arc sound like? We don’t want anything to distract from the message. It’s something we all nudge together into place like this dough.

MEYER: A couple of records that come to mind for me are the Deerhunter record Halcyon Digest, which has a very complicated arc to it. I think that’s a perfect record. I love it so much. Kid A is another one that comes to mind, maybe even more so, because that really is divided into two halves, with “Treefingers” dividing it up. That’s definitely the record I’ve listened to more than anything else. When I heard that as a teenager, it was one of those “Oh shit, music can do this?” moments. I know, for some really good reasons, no one’s super high on Radiohead right now, but that’s a really unbelievable record.

It’s interesting that the record has survived as a format that we’re still really into, even through so many different physical mediums. The record comes out of vinyl, but then it sticks with us all the way through DSPs, I think because it’s almost like a show for an artist. It’s a really nice way of packaging a certain moment of creative time. There’s a few ways of approaching records. One is the Slayer model — Reign In Blood, 28 minutes long, perfect fucking record, couldn’t be better. But it’s kind of just one thing. A lot of metal records work that way — Cannibal Corpse too. If you threw on a track from Eaten Back To Life in the middle of Tomb Of The Mutilated, you might not know you were in a different record, because they were just perfecting this one thing. The other approach is to just create a long and winding road that leads to your door in a confusing way. I think that’s what we were going for here. Part of how we were approaching making this record was making something that’s complicated formally. One of the things that’s exciting for me as a listener is when I don’t understand what an artist is doing.

I don’t think this is going to be a super compelling listen for passive listening, so we’re shooting ourselves in the foot. We’re trying to create a record that really rewards active listening. The connections between the two halves and song-to-song really make sense if you’re listening to the record with a little bit of focus and breathing space to make connections as a listener. What the record is not doing is creating a vibe for you to listen to for 40 minutes. The Spotify vibe thing obviously sucks, but Slayer makes a vibe, in the sense that those songs bang, but there’s a vibe that you have for the 28 minutes that record goes on. That’s just not what we’re doing. We’re not just trying to throw shade at music that creates a certain vibe. It’s more about whether you’re doing something that feels uniform across the duration, or something that jumps up and down.

Alex G

MEYER: I think he’s a real, actual genius. In that earlier work, there’s some consistency to it. But there’s some real confusion on Rocket and House Of Sugar that’s really exciting to me as a listener, where I go, “Wow, that’s a really weird choice,” but you trust him as an artist. He released “Brick” and “Sportstar” as the last singles from Rocket, and that came after “Bobby” and “Witch,” the latter of which is one of the weirdest singles I’ve ever heard. I hope people trust us in the same way, and roll with the weird choices and give it a couple listens and see how it all fits together.

Bob Dylan

MEYER: There was this one tweet someone made about Bob recently that was so good: “it’s so crazy that Bob Dylan is a real guy. a vagabond jester beloved by millions for songs he refuses to sing, who travels the world telling lies.” Bob is most of what I listen to, by a pretty wide margin.

it’s so crazy that Bob Dylan is a real guy. a vagabond jester beloved by millions for songs he refuses to sing, who travels the world telling lies

— jon repetti (@pourfairelevide) July 15, 2025

HAUG: Not exaggerating.

MEYER: 50-60% of my listening diet is just Bob. The rest is everything else. It just feels like an ocean to jump into. There’s just an infinite amount of material there, because there’s 33 studio records, and all of them are at least interesting, even the ones that are clearly bad. There’s definitely some stinkers in there, but they’re bad in a way that’s pretty fascinating. I think the thing with Bob is that it’s never clear what he’s doing, even on the protest music stuff from the early ‘60s where it’s almost didactic music. He’s like, “This is something that happened and it’s bad,” and it’ll be on a record alongside some really silly stuff that seems to throw some confusion into it. And then there’s the famous example of someone asking him what “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” is about, and he’s like, “It’s about a vacation I took.” What I take out of it that’s interesting to me is this sense that it’s more exciting to offer a listener breadcrumbs than it is to leave them a trail.

I think that’s a thing that people who love him enjoy — there’s this constant perplexing thing to the decisions he makes. They never make obvious sense, and it’s confusing to figure out why he’s doing them. I think that’s a compelling position to be in as a listener. Part of what excites me about that, in terms of bringing it into our music and practice, is thinking, “How do we create a situation that is dynamic and confusing as a listener in a way that’s also stimulating?” That’s my favorite position to be in when experiencing any form of art, and I think Bob is the master of it.

That brings to mind the kind of genre-specific ways Dylan obfuscates. Like, obviously, with metal, there can be a kind of lyrical obfuscation just by means of vocal performance. But with Bob, it’s this often crystal clear hyper-verbose vocal performances, but he leaves so much to the listener to piece together what the meaning is behind the words you’re hearing.

MEYER: 100%. I think the other thing people sleep on with Bob sometimes is that the live stuff from the ’60s and ’70s is un-fucking-believable. Speaking to your earlier point of records with two halves, there’s the famous live recording from 1966 at the Royal Albert Hall where the first half of it is him with his acoustic guitar with this unbelievably beautiful and tormented version of “Visions Of Johanna” and the second half has the band come out. That’s the one where, right before “Like A Rolling Stone,” he’s like, “We’d like to dedicate this song to the Taj Mahal.” He’s sneering in a way that’s kind of embarrassing, but then they just play, and it’s some of my favorite live music ever recorded. That’s a huge influence on what we do. At the end of the day, we really are a live band. That’s something I take from him. He never multitracked anything — it’s always about the live performance. We obviously don’t do that… or, actually, we do do that. Maybe write that. Let’s start lying a little more.

Get some of that famous Bob Dylan interview trickery in there.

MEYER: I always want to lie to press, but then I always like everyone we talk to and it feels rude to do it. That aspect of being the best live band is something really motivating for us.

I’d love to hear from the rest of you about what you observe tends to be the Bob record that gets played the most when you’re on tour.

HAUG: Leah pointed this out, but Dan will be like, “This will be the worst Bob Dylan record. Check it out.” I feel like that’s how it started. Now it’s just everything. Tempest has been our house music when we play shows.

MEYER: It’s the best.

CHOWENHILL: It’s been interesting, getting all this later Dylan in the van. I was not familiar with those records. My dad was a bit of a Bobhead, so I was familiar with the work through the early ’70s. It’s just a different kind of music and presentation, but it’s so cool. It’s really interesting to be like, “This year, this is my idea. This is what I’m doing.” Sometimes, we’ll be in the van and I’ll be waking up from a nap, and there will just be a new thing on, and I’ll be like, “Oh, this is another Dylan record from another period, and he’s just doing another thing.” Half the time, Dan will be giving a lecture on it, and the other half of the time, we’ll just be listening to it. It’s been a really fascinating musicological journey for me through the entire discography of Bob. It’s definitely one of the more interesting elements of van life.

MEYER: The thing about Bob that I like to bring up is that there are really, really bad Bob records, but they’re fascinating.

I love telling people that I’m a big Self Portrait defender. I find that record so deeply fascinating.

MEYER: Oh, amazing. I also think that’s, to be honest, a good one. I think of maybe Knocked Out Loaded or Saved as ones that are bad. Down In The Groove is probably the worst one. We’ve listened to “Ugliest Girl In The World” a lot, with the backup vocals by his wife at the time. That one’s so insane. Being a Bob fan feels like being in on an inside joke that you’re actually not in on, but you can pretend to be in on. That’s the kind of band I’d like to be.

So what you’re saying is that the next radical reinvention for Agriculture is all that you’re going to do new live reinterpretations of all your songs.

MEYER: Yeah, you won’t know which song it is. I’m actually just going to start playing piano, which I don’t play. [Laughs] I think we will truly become a Christian band. Please print that. Make that the headline.

The Spiritual Sound is out 10/3 via the Flenser.