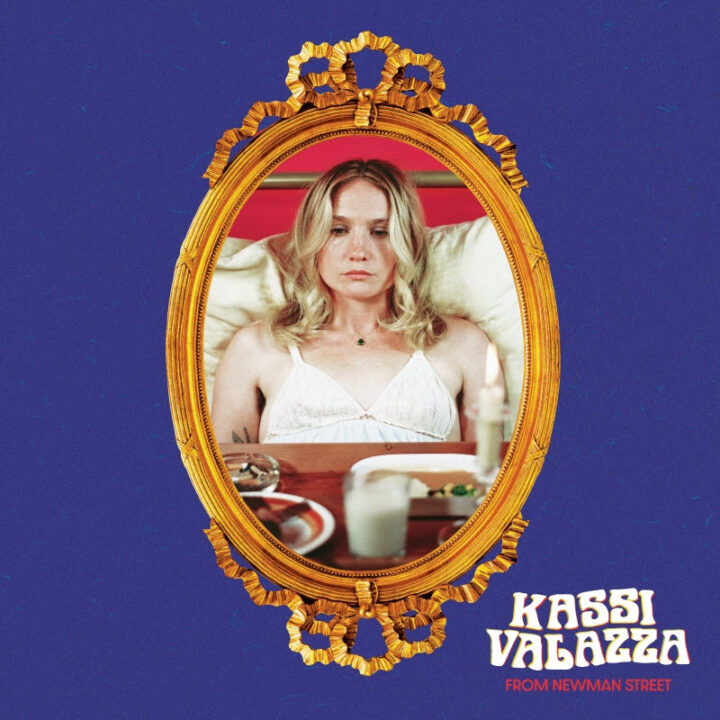

The Story Behind Every Song On Kassi Valazza’s New Album From Newman Street

When I get a hold of Kassi Valazza at her New Orleans apartment, she’s only been home for about 12 hours. She just flew in from Portland, where she lived for most of the past decade, to play a homecoming gig at the famed Laurelthirst Pub. Before that, she was in Australia for three weeks, opening for the folksinger John Craigie. (Valazza didn’t get to meet a koala, like every other band on your Instagram feed seems to when they tour Australia, but she did meet a quokka: “They come right up to you, and you can pet them, and they’re very cute.”) She’s exhausted. That’s the gig.

“When I first put out the Knows Nothing record [in 2023], I was like, ‘I’m just gonna tour. That’s all I want to do,'” Valazza says. “I still love it. I think I’m reaching a point, though, where I feel like my creativity is coming to a halt from all the touring and the traveling. I’m also sick all the time. I’m sick now. I just feel like my body’s giving up on me a little bit, and so I would like to take a little bit more time to focus on writing.”

Valazza is a songwriter’s songwriter, the kind of lyricist who makes it embarrassing to describe her with such a cliché. Across three albums of thoughtful, increasingly ambitious folk music, she’s carved out a reputation for her sharp pen and even sharper ear. Equally indebted to Laurel Canyon-era Joni Mitchell, Sandy Denny-era Fairport Convention, and the humanistic freak-folk of the late Michael Hurley, whom she collaborated and toured with toward the end of his life, her sound straddles just about every folk subgenre without truly belonging to one. When she pulls up to the honky-tonk with a pedal steel player in tow, don’t expect a night of strictly country music. Genre fetishism isn’t Valazza’s thing. The writing’s the thing.

From Newman Street, Valazza’s third album, contains her most incisive writing yet. Penned between Portland and New Orleans in the midst of her protracted move south, it gets at the anxiety and confusion of a life in flux, when self-destructive cycles are still only partway through being dismantled. Valazza sorts through that unsettled feeling with clear-eyed perspicacity. Still, “it’s easier to say than to practice what I know,” as she points out on the lushly arranged “Weight of the Wheel.” She’s good enough to pull one over on us, but too smart to let herself get away with it: “Disguised as poetry, it lands/ But you’re feeling loathsome, you’re feeling bad.”

If this album was at least partly informed by the chaos of feeling stuck in a perpetual in-between, Valazza knows the next one has to be different — hence her desire to spend a little less time on the road. Already, she has plans to leave New Orleans, making From Newman Street a time capsule of a period that’s almost over.

“Typically, I don’t write well moving,” she says. “I need a lot of groundedness, and I need quiet and space. Honestly, since these songs, I haven’t written anything new, because it’s just been constantly going, and touring, and adjusting to a new city.”

Valazza recorded From Newman Street in Portland with her full six-piece touring band, who are also credited as her co-producers and co-arrangers. Below, you can listen to the album and read our track-by-track interview.

1. “Better Highways”

You covered “Wildegeeses” by Michael Hurley at the end of the last album, and at the beginning of this album, you’ve got the lyric about “the wild honking of the sulking winter geese.” Was that an intentional echo?

KASSI VALAZZA: Yeah, that was definitely my Michael Hurley line. That was me putting a little Hurley in there. But there’s not a whole lot of meaning to it. I just wanted to sprinkle a little Hurley in there.

It’s nice to have it there, obviously, in light of his passing. You got to know him pretty well in his final years. What will you remember most about having a creative collaboration with him, but also just a friendship with him?

VALAZZA: I think just how playful he was. He was just so playful in the studio, and when we were playing music together, and just in life. I think I have like a bad habit of taking things so seriously. After spending so much time with him, it’s a good lesson to know it’s okay to be goofy and to just play.

“Better Highways” is about the impact that even our most fleeting relationships have on us. Is he on your mind at all when you think back about that song now?

VALAZZA: Yeah, totally. But you know, I think it changes. Some songs aren’t even about one specific person. And that’s what makes art so special, is it can be reflective of whoever you’re around, or whatever you’re going through in that moment. And I think “Better Highways” is an example of that.

2. “Birds Fly”

Are there field recordings of birdsong on here? Or is that all being created with instruments?

VALAZZA: It’s all pedal steel.

That’s a really cool effect. Was that something you figured out on the day? Or did you have a plan to do that?

VALAZZA: I think what happened was I was going on tour to the UK for the first time, and I have a trio of Tobias [Berblinger] and Erik [Clampitt], who is playing pedal steel, and we were practicing before we took off, and I just remember I was playing it, and he just started adding these little sounds. And I was like, “That sounds like a bird!” And he just kept doing it, and then it grew. So yeah, that was Erik’s idea.

That’s cool. Thematically, this feels like a heavy one. What exactly was going on around you in Portland that inspired you to write it?

VALAZZA: I don’t know if it was just, like, post-COVID, or if the world was really heavy. It still is, but at that time it felt like it was as heavy as it could be. And a lot of people in our community were drinking a lot, and dying from fentanyl overdoses, and I was hiding in my basement while all these people I loved and knew were out, just raging it. It felt like a really dark, intense time. I felt like I was watching the world move really fast from a window or something, and it was really intense. A lot of it was just drugs and alcohol, that kind of stuff.

When you’re dealing with a subject that inherently blunt and raw, is it challenging to transform that into a song? Or is that just how it processes for you?

VALAZZA: Maybe. I don’t know. I think I don’t know how to answer that. I think sometimes songs just come out, and that’s just how they are.

3. “Shadow Of Lately”

This song references your friend, the visual artist Boramie Sao. You did a beautiful shoot with one of her paintings in the desert for the single release. Let’s start there: What role did she play in inspiring “Shadow Of Lately”?

VALAZZA: Creatively, she’s just, like, my soul sister. We do a lot of stuff together creatively. And she moved from Portland when I was still living there, and that was really a hard transformation for me, because I was like, “Oh, I have to face the city, and making art, by myself.” It just seemed like a big thing at the time. And also, realizing that I wasn’t quite happy where I was. I was like, “Do I go to Taos? She’s in Taos. Do I go to Nashville?” There was just a long period where I was like, “I don’t know where I’m supposed to go.” But I’m really happy that Bo has found her space, and she’s thriving.

So did you know, as you were putting those kinds of feelings into this song, that your time in Portland was just about up? Did it feel over?

VALAZZA: Yeah, I think so.

Was it difficult to be creative, knowing that? Did that demotivate you at all?

VALAZZA: No, I think that’s when I was most creative, because I think I knew that a change needed to happen. And sometimes, when that happens, you’ll just get up and be like, “OK, I’m gonna make the change.” But for the first time in my life, I really sat with it. I was like, “I’m not gonna make any moves. I’m just gonna think about what I really want.” And while I was doing that, I was at home. I was sitting around. I was writing songs. I was coming up with melodies, and I think it really helped in that process.

I love the use of Mellotron and pedal steel together here. I think those two things should be together way more often. What do you remember about figuring out the arrangement for the song?

VALAZZA: Tobias is so good. He plays the Mellotron. I feel like he’s just so good at the padding, and creating the overall vibe, which is what the Mellotron is for. And then Erik just came in with that lick on the pedal steel, and it’s just so beautiful. I don’t know. It just felt like everything kind of fell into place with this song when we were working on it.

4. “Time Is Round”

I’m a big Fairport Convention guy, so I couldn’t help but hear a little bit of “Who Knows Where The Time Goes?” in the lyric to this one. I don’t know if that was subconscious, or if that was on your mind at all.

VALAZZA: Yeah, you know, it’s funny. I was worried about that when I wrote it, because I love that song. I obviously love Fairport Convention. But that wasn’t my intention. That’s just what came out. A lot of times when I write it’s just, you know, whatever comes out. I’m not thinking about it. And [“Where does the time go?] just came out, and I kept trying to change it. It’s always hard when it’s the first line of the song, because for some reason, that always feels so cemented. It’s really hard to change, for me, the first line of a song. And so I was just like, “Fuck it.” It’s just, that is what is happening. And it is how I felt. But it’s not the worst comparison. I love Sandy Denny and Fairport. But yeah, I really wanted to avoid that, and sometimes, that’s just what happens.

And then a journalist calls you out on it.

VALAZZA: [Laughs] You’re not the first person to say that.

I think it’s a cool, if unintentional, nod. You repeat the last line, “I feel like an old woman these days,” four times, and that feels like a kind of an anchor line for the song. Where does that feeling come from for you? What was making you feel that way at the time?

VALAZZA: Well, I just moved to New Orleans, and I felt like maybe I wasn’t quite fitting in. I’m not an outwardly outgoing person. I’m pretty insular, and I keep to myself. I think it was hard adjusting to New Orleans, because it is a very loud and exciting place. It’s so many people, so much celebrating, and I felt like I was kind of like this grumpy old woman. Which, I’ve I felt that way before, because there were periods of my life where I wasn’t drinking, and everybody I knew was drinking. And it’s just that feeling of, “I can’t keep up with everybody, and I don’t want to keep up with everybody.” And trying to be accepting of that and holding space for yourself while you’re going through that.

So it’s not even a negative thing, the way that you’re saying it. It’s just an observation.

VALAZZA: Yeah, totally.

Because I brought up Fairport, and since you said you love Sandy Denny, I was thinking about your voice. You both have that sort of high, clarion, minimal-vibrato thing. You tend to play in these country, honky-tonk-type settings, at least in America, but your voice doesn’t necessarily lock you into that world. Do you worry much about genre, or where the music you make falls?

VALAZZA: I think I try not to. I think I get paired with a lot of honky-tonk stuff at a lot of venues and a lot of shows, which never goes well. I feel like it’s a funny thing, just because country is so big in the States right now. Maybe in general I feel like people don’t really know where to put me. So because I wore a cowboy hat on my first album, they’re like, “Just put it over there with all the other honky-tonk people.” Which is fine, because I love those people. I’m friends with a lot of those people. But it doesn’t always feel like I have a home, or like I fit anywhere. I think that’s also a positive, and a cool thing. And it’s funny, because when I go over to the UK, I don’t feel that way. I feel like people in the UK kind of get it a little bit more. In Europe, in general, they tend to get a little bit more. It’s definitely an American thing.

That’s interesting. I don’t think it’s a bad thing, like you said. Maybe it’s better to stand out than it is to fit in.

VALAZZA: I don’t know. There’s been a few disappointed people, for sure.

“Where’s your fucking cowboy hat?!”

VALAZZA: [Laughs] Actually, in Australia I had somebody come up and be like, “You’re not wearing your cowboy hat.”

Oh, my God!

VALAZZA: Yeah. I’m like, “I haven’t worn a cowboy hat in 15 years.”

5. “Roll On”

You said that this took 13 tries to get right? What was so tough to crack about this song?

VALAZZA: I think person that I said that to in an interview misunderstood what I was saying.

Oh, okay! Set the record straight.

VALAZZA: I think what I meant was about the subject matter. It took me 13 times to get this relationship right. Like, I was like trying so hard to make a relationship work that wasn’t working. And then I finally realized, “Oh, you gotta just let go of it. It’s not working.” And I think she took that literally as like, “Oh, the song.” But no, I just meant the experience of what I was going through at the time. I just kept trying and trying, and it just was for nothing.

So was the song easy?

VALAZZA: Yeah, the song came so easy. It was, like, in a day. It was one of those songs that you just write in a day, and you’re done.

6. “Your Heart’s A Tin Box”

The drums, and the strumming, and the little lilting guitar figures on this make it jump out right away. Did you know that this was going to be a more uptempo song right when you thought of it?

VALAZZA: Yeah, definitely.

Where did that come from? What made that feel right?

VALAZZA: I was listening to a lot of Paul Simon, Rhythm Of The Saints, and he has all of that amazing, incredible percussion on that album, and a lot of the songs are really upbeat. And I don’t write a lot of upbeat songs, so I really wanted to try something different, and create a different feeling than I usually do.

The lyrics have this anxious energy to them, and the groove of the song feels like it mirrors that energy. Was that the feeling you were trying to convey?

VALAZZA: Yeah, I guess? I don’t know!

It’s okay if not!

VALAZZA: I don’t know. I guess I wasn’t thinking about it as a whole. I was like, “I want it to sound like this.”

Do you feel like it is a song that has an anxious or nervous core to it, at least lyrically?

VALAZZA: Definitely.

You wrote you wrote it in New Orleans, right?

VALAZZA: Yeah.

What emotions were going through your mind as this one was coming to you?

VALAZZA: I’ve never written a song that sounds so much like me. I feel like that song really does represent how I sound on a day-to-day basis. I’m a pretty anxious person. I’m pretty nervous all the time, and I think moving somewhere new, and feeling like I didn’t fit in, and then being worried about not having money, because you don’t make any money as a musician these days…So many things just felt like they were piling up. And I just found a way to write it all down, almost like a diary or something.

Are you at a different place with the emotions of the song when you hear it now? You’ve been in New Orleans for a while.

VALAZZA: I don’t know. It’s funny, I’m not here very often. I’m gone all the time. And I think that’s what makes adjusting so hard, is I’m just gone all the time. But it’s a cool city, and I’m glad to be here. Listening back to that song, I’m actually really proud of those lyrics, because I feel like, they really do represent how I feel, which is reassuring and validating.

Do you feel locked into sticking it out in New Orleans, even though you’re not there very much?

VALAZZA: [Laughs] No, actually, me and my boyfriend are gonna move to Nashville in November.

So this will be the New Orleans record. The next one will be the Nashville record.

VALAZZA: Yeah, exactly.

7. “Small Things”

You said that this one started as a poem and became a song. Does that happen often to you?

VALAZZA: Yeah, definitely. Most of them are poems.

Do feelings just sort of subconsciously manifest as poetry for you, and you have to run to the notebook and get it down? Or do you have to make a conscious point of sitting down to write?

VALAZZA: Usually I have to make a conscious point. There’s been a few times where a line will happen, and I’ll run and go write it down. Very rarely, but that has happened before.

What’s the transformation look like for you, when you have some lines on a page, and then you want to turn it into a song?

VALAZZA: I think that’s always different. I think as I get older, there’s more revision that happens, and there’s more time that gets put into it. I think when I first started writing, it was like, whatever came out is what it was. And I think now I do that a lot less, and I really focus in on a song, and I take my time with it. Sometimes I’ll have a skeleton of a song, and I’ll go for a walk, and I’ll listen to it on my voice notes over and over again, and I’ll try to find different words or different ways to say what I’m trying to say. It’s usually a much longer process these days.

Does a melody ever appear alongside the words, or are those pretty much separate?

VALAZZA: Yeah, sometimes it does. “Time Is Round” was one of those where it just kind of all came out. And those are the magical ones. A lot of times, especially lately, I get the melody before I get the lyrics, and then I’ll add the lyrics to it.

8. “Market Street Savior”

What is the Market Street that you’re talking about on the song? Is it in Portland?

VALAZZA: I think I was talking about San Francisco, because I had just played in San Francisco, and I think that was just running through my head. But I don’t know if it’s necessarily about San Francisco. I think it’s just a song about being in a place that used to feel comfortable, and now you feel very far away from it.

A familiar feeling for you?

VALAZZA: Yeah, definitely.

This one has really sunny melodies, and really bright vocal harmonies — the ooh-ooh parts. What made this song feel like it warranted that kind of treatment?

VALAZZA: I really liked the melody where the oohs were in, and I didn’t want to add lyrics to it. And I was like, “Well, the only way that’s gonna work is if I really do something with those oohs.” So I had Camille [Weatherford] and CJ [Reece-Kaigler] from the Lostines sing on them. And yeah, they got that kind of mermaid-y, siren-y sound.

9. “Weight Of The Wheel”

I’m curious how this song ended up being track 9. I’m kind of a sequencing nerd, and this is the lead single. You’ve been playing it live for a while. You’d think it would at least be on side A. What was the process that led to it being way down here?

VALAZZA: I had a couple of band members that were like, “It needs to be on side A!” But I think you need to space it out. I love “Weight Of The Wheel,” and I do think it’s one of the better songs. But I think you can’t put all the good ones on side A. You gotta spread it out, so people listen to the whole record. And if they don’t listen to the whole record, then they miss out. I also think just placement-wise, it just sounds good right there. I still listen to records like records, so it really is just a matter of what sounds best where and what makes sense. It’s not about, “Put it on side A because more people will hear it.”

It also feels like a thesis statement for the album. Lyrically, it feels like you’re capturing a lot of the feelings that are at the core of this record. Did it feel that way to you?

VALAZZA: Definitely. This might be the first song that I wrote for this record, and I think everything just kind of came after that. Something about that song, it made all the other songs make sense.

This image of the wheel, and the cycles that we struggle to break—how did that come to you?

VALAZZA: I think just being unhappy, doing the same things over and over again, trying to make something work that’s not gonna work. I went through a few different relationships in Portland, where I was trying to make things work, and they weren’t working, and I was getting mad at myself without realizing that sometimes you just have to break it and walk away.

10. “From Newman Street”

For the most part, this is a full-band record. And then we get this one very stark song, that’s just voice and guitar. What went into the decision to do it that way?

VALAZZA: I think it’s good to have dynamics on records, just to give your ears a little break. But also, I wrote the song like that, and I just think it sounded best like that. It was a very solitary moment when I wrote it. I was missing a friend of mine that wasn’t there, and I think it just felt like a very private, intimate, sweet moment, so I wanted to keep it that way.

Why did it end up being the title track? Why did this feel like the right name for this collection of songs?

VALAZZA: I think I was feeling a lot of heavy, sad feelings while I was in this house, writing these songs. But overall, I think I was kind of finding my voice, and figuring out how to do things. And there was this positivity, and also this playfulness, that came from learning how to do all these things, how to make all these changes. And so that song, to me, ends it on a positive note, which is how I look at that whole experience. In a very positive way.

From Newman Street is out now via Fluff and Gravy Records.