We’ve Got A File On You: Dean Wareham

Laura Moreau

We’ve Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

“There’s no difference between the blue and the red/ The cloud is coming for us all,” Dean Wareham sings at the very end of That’s The Price Of Loving Me. There’s a touch of political commentary felt with the line, though the power of it comes from its finality. The specter of death is faced straight on as Gabe Noel’s cello rises and swirls, and Wareham’s bandmate and wife Britta Phillips joins in singing the same words in unison, sonically right by his side.

That energy hangs over all of Wareham’s freshly released solo album, a gorgeous collection of the types of songs he’s built a reputation for knocking out seemingly effortlessly over the past 35+ years. Yet beneath all that beauty, and there is plenty to spare, is a record shaped by loss and frustration with the current moment. “Mystery Guest” is a scattershot tribute to a now departed friend. “Yesterday’s Hero” and “New World Julie” touch on the rise of student protests and breaking laws in order to change the world, respectively. Even the choice of cover, Nico’s “Reich der Träume (Land Of Dreams)” speaks to the all too relatable desire to escape into everlasting sleep.

This new album also reunites Wareham for the first time in 34 years with producer Kramer, who worked on every Galaxie 500 album and was instrumental in establishing their signature reverb-soaked sound. And while his touch can be felt throughout (the warmth of the guitars, the lack of anything showy or distracting), That’s The Price Of Loving Me is in many ways like a commutation of everything Wareham has done over his career rather than any sort of grasp towards nostalgia: the quiet melancholy of Galaxie 500, the wry lyricism of Luna, the less-is-more mentality of Dean & Britta is all there.

A few weeks ago over a Zoom call and an occasionally flakey internet connection, we talked about the making of his new album, Noah Baumbach’s production team yelling at him, unintentionally upsetting people with his memoir, how Sonic Boom is a modern musical genius, Lou Reed losing his ability to sing in the ’90s, his methodology of how he approaches the songs he covers, and more. Below, stream the new album and read our conversation.

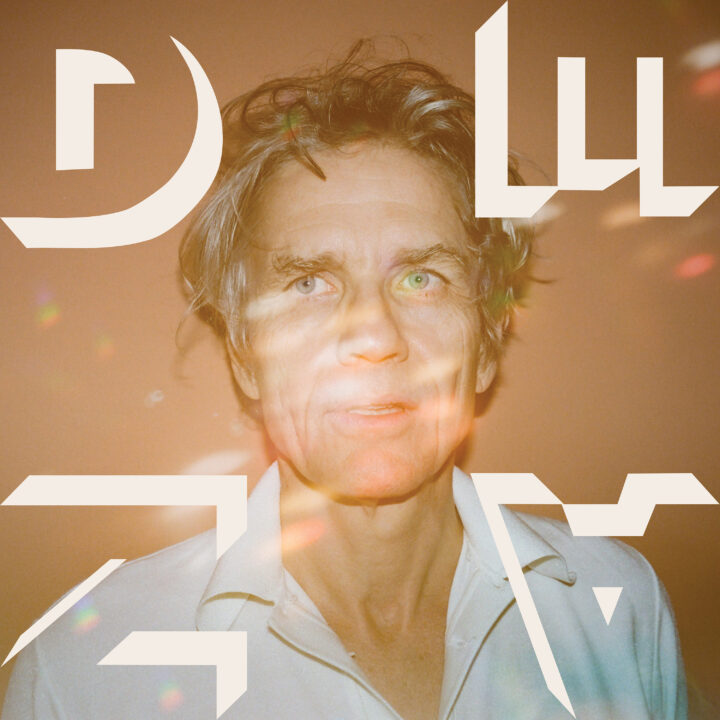

That’s The Price Of Loving Me (2025)

Do you remember the exact moment you wanted to work with Kramer again?

DEAN WAREHAM: I wanted to somewhere in the back of my head. He kept reminding me, “It’s crazy we haven’t made a record together.” I was out here in LA, and I’ve made my last few records with Jason Quever of Papercuts and was happy working with him. But then Kramer came out and visited LA, and we played a few songs together. A friend of mine passed away a couple of years ago, and it kinda hit me that we’re not here forever. Talk is cheap, and it’s easy to keep saying, “Yeah, we’ll make that record. We’ll make it one day.” At a certain point I just said, “Let’s do this, I should do it now.” I don’t remember what the day was, no. Maybe when I put a deposit down on the recording studio. I’m not one of those people who gets up and writes songs every morning. If I boOK studio time then I’ll be like “OK, I’ve got studio time, I’ve got to finish these songs. I’ve got 20 half-baked ideas, I better get to work or it’ll be embarrassing.”

Was it like you remembered? You’ve talked about in the past how Kramer works kinda fast, sort of “first thought, best thought.” Was it like that 34 years later, or has his style changed? Have you just gotten more comfortable in the studio?

WAREHAM: Well obviously I’ve made a lot more records, I feel more comfortable singing in front of a microphone than I did in Galaxie 500 where it was like, “Whoa, we’re in a recording studio and what’s this?” But as for his basic methodology, he likes working quickly. If he’s working in the studio, he’s working. Not sitting there telling boring stories, avoiding work. It can happen to bands certainly the longer you’ve been making records, you can go into a studio and just waste time. Yes, he believes in first thought, best thought. I offered to send him demos and he didn’t want to hear them even. He was like, “No, I’d rather hear them in the studio and whatever arrangement ideas pop into my head they tend to be better if they’re like a new idea, rather than if I’ve had a song running in my head for a while.”

When we did the live tracks I guess it was like two takes of each song, and then you quickly make a decision. But when it came to me overdubbing my guitar solos again, I was allowed two takes maybe. He was like, “OK do this, now this. Now play it up here on the neck. OK we’ve got it.” And I was like, “Eh, I could probably work on that longer.” [Laughs.] Then when I heard the mixes I was like, “Well, he kinda knew what he was doing all along. He’s got this song building in his head from the get go. So yeah, it was pretty much the same methodology: basic tracks, do your vocals, do your guitars, and then whatever other elements he thinks it needs.

Was it more collaborative this time around?

WAREHAM: Well, we’re all playing, and he’s playing more on this album than he did on the Galaxie 500 albums. But when you work with him, he’s in charge. But it’s nice in the studio for someone to be decisive. There’s this joke, “How many producers does it take to screw in a lightbulb? I don’t know, what do you think?” [Laughs.] It was six days, which is pretty damn quick. Then he went out to mix, but it was already in pretty good shape for mixing. He had it all really dialed in. And we both know more than we did back then. I think he knows a lot more about engineering and software. Well, there wasn’t software back then. Back in the olden times you couldn’t see the music, you could only hear the music and you had to use your ears.

Galaxie 500’s Archival Compilation Uncollected Noise New York ’88-’90 (2024)

You also released Uncollected Noise by Galaxie 500 last year. Was it weird being in the studio with Kramer and relistening to your first recordings with Kramer?

WAREHAM: Listening to those recordings, even the ones that aren’t our best songs — and they’re not our best songs, that’s why they stayed in the vault all this time — it just sounds cool. It’s just the three of us in that room, and the guitar sound I had then, it’s like there on every song. So it was exciting. Was it weird? Yeah it’s a little odd. I don’t know if it’s a record, to work with someone 34 years later, I don’t know how often that happens in the music business.

There’s actually a Nancy & Lee album they did with arranger Billy Strange called Nancy & Lee 3 that come out in 2004 I was pretty excited about, and it wasn’t very good. [Laughs.] The production wasn’t good. I think that’s something people can lose sight of as they get older is just what’s good production and what’s bad. What’s nice sounds and what’s horrible sounds. I think we got good sounds and sort of natural sounds. I think part of why the Galaxie 500 stuff sounds good is because it sounds a little odd. It doesn’t sound like the 1980s because it’s the late ’80s, trying to get out of the sounds of the ’80s in a way. But it doesn’t sound like the ’90s either.

You were trying to find something different, and even if you didn’t find something different because you were trying to find something different it sounds special in it’s own way?

WAREHAM: On those early recordings? We were just doing our own thing. We weren’t listening to what was on the radio, so I guess we were listening to Paisley Underground bands maybe. Whatever we were listening to, we were also self-taught musicians, so whenever there is a gap between what you’re aspiring to and what you can achieve, in that gap is maybe what is unique about us and interesting about us.

“Anesthesia” 7″ With Mercury Rev Members Grasshopper And Jimy Chambers (1991)

Jumping ahead a little bit, when you released the Anesthesia 7″ right after Galaxie 500 broke up, did you think you were going to go solo, or did you always know in the back of your head you wanted to form a new band?

WAREHAM: I wanted to form a band. It was different times. I feel there were less singer-songwriters around. There’s a lot more of that now. I also just felt like I was interested in the textures that bands create together instead of one singer-songwriter hiring different people every time. So I knew I wanted a band, but I wanted it to be a four-piece band not a three-piece band.

Did it instantly feel different playing with the Mercury Rev guys instead of Damon & Naomi?

WAREHAM: Well, the only one…oh right, because Jimy Chambers plays on that one song “Anesthesia.” I didn’t know a lot of drummers, and here was one who would be down to play. And Grasshopper wound up being in Luna just for a brief time. Well, it’s always different playing with different people, and you learn from everyone you play with. I had been in the studio with Mercury Rev to sing and play on “Carwash Hair.” Sleeping on the floor of the studio. It was interesting watching them work as well. In Luna we all sit in a room and play things live. They just build things on top of each other. I’ve always preferred it [our way]. To me it’s easier. You just immediately get a sense of how a song works.

Scoring Noah Baumbach Movies Including The Squid & The Whale (2005)

How did you meet Noah Baumbach, and how did that lead into doing soundtrack and acting work for him?

WAREHAM: I met Noah I want to say ’94, ’95 when he made his movie Mr. Jealousy. We were introduced by his music supervisor on that film. That’s Noah’s second movie. And then maybe I mentioned I used to act in high school and he was like, “Oh, why don’t you come down and do a scene in Mr. Jealousy?” So I came down and had to do a scene with Annabella Sciorra the actress. I was just some douche guy, music video director at a party. Anyway, I just had to stand next to her, and I was so nervous my hand started shaking like this. [Gives his hand a small, noticeable tremor, then laughs.] Also the DP kept coming up to me, “You’re blocking her shadow! You’re blocking her shadow!” It turned out fine.

But I stayed in touch with Noah, and it took him like six years to make The Squid And The Whale. And by that time I was living with Britta, and we started doing the score together in GarageBand in our apartment. Because there was no money, it was a low-budget movie. That was fun. We’ve scored a number of films, and it’s more fun to score a good one than a bad one. Sometimes when scoring a movie, someone gives you a scene and you’re like, “This scene is horrible. Do you want me to fix it?” [Laughs.]

Dean & Britta’s 13 Most Beautiful…Songs For Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests (2010)

Do you think doing the soundtrack work prepared you for when you did your Andy Warhol material, or do you think you would have done that regardless?

WAREHAM: Well, I guess doing a film teaches you you’re there in service of the film to make it better, and even if you’ve written a good piece of music it might not work for that scene. The Warhol thing, that was kind of a challenge cuz each of them was like a four-minute music video where the video is made for us and you have to put some music to it. And also we had to perform them live, so we had to think about that. That was nerve-wracking. But again, pretty incredible to work on those incredible films. His films are challenging. Everyone loves Warhol the painter, the flowers and Elvis paintings and all of that stuff, but the films remain quite challenging to this day.

As a live performer, do you find performing on stage different than performing on a camera? Do you like it more because you can make mistakes and fix them, or is it a different sort of pressure?

WAREHAM: Well, having been photographed plenty and played on stage plenty, that does calm me down. I’ve acted for him since, and I calmed down a little. I’ve gotten better, or I don’t get so terrified anymore. But I think my approach is the same, just to be myself. Even if my character is different each time, just try to bring that character close to myself. Do something that’s believable. Some things are within my range as a singer, the same thing as an actor, and some things are not. That’s what you learn to do. In some ways acting is easier. They write all the words for you, all you have to do is stand there and say them.

Is it like covering a song?

WAREHAM: [Laughs.] Yeah, in some ways you’ve got to figure out if you can convincingly deliver that “song,” if you can find the right attitude in it. Some songs are harder than others. For me, instead of trying to sound like Robert Plant, I’ve got to find a way to bring that closer to me, to myself. And then there are some songs — Led Zeppelin songs are good examples of a song Luna should not have covered because it didn’t really work out because I couldn’t really convincingly do that.

Luna Covering Paula Abdul’s “Straight Up” For The Compilation Guilt By Association Vol. 1 (2007)

I’m curious about that because you’ve covered “Straight Up” by Paula Abdul and your “Sweet Child O’ Mine” cover, you’ve talked about how that’s not really a band you love. But you have covered songs you do really love. How do you thread between the two?

WAREHAM: I mean, usually I cover a song I love. Usually that’s the decision, to cover something you like or no one has heard of. The Paula Abdul song was for an album. The concept was guilty pleasures, and the music supervisor Randy Poster suggested that song, and I was like, “Well, this is not a guilty pleasure, I just don’t like it.” [Laughs.] Hopefully I found a way to make that song sound more intelligent than it actually is. and I sorta just talked my way through it. That’s a trick an actor told me once. If you don’t like the dialogue, if you don’t think it’s well written, just say it as quickly as you can.

Do you like being loyal to the songs or do you like reinterpreting them? Because I’m thinking of Galaxie 500’s version of the Modern Lovers’ “Don’t Let Your Youth Go To Waste” where you had to basically build a second half to it?

WAREHAM: Yeah, we basically cowrote that song. We should have taken half the publishing on it, but we didn’t understand how things worked back then, that [Jonathan Richman’s version] was just kinda reading an a cappella poem. Yeah, I like to go somewhere different with it. Usually that’s just slowing it down or making it more atmospheric. I really hate a lot of lame like punk covers of songs; that doesn’t do anything for me. It’s just a way of finding your way into the vocal. One of the hardest songs I had to cover was Bob Dylan’s “Most Of The Time.” I listened to all different versions of him doing it and just trying to figure out what the melody was, and it occurred to me maybe Dylan didn’t even know what the melody was. It sort of seems like that. In a way, what he did in his vocal on that song is like a brilliant acting performance. Made me appreciate him as a singer. With him it’s all about the phrasing and the attitude of being Bob Dylan. I think Lou Reed is the same. Anyway, I got there eventually.

Touring With Lou Reed And The Velvet Underground

When you wound up touring with Lou Reed did you get a better understanding of him as a songwriter as a fan of his, or did his mystique continue on?

WAREHAM: When I was touring with him it was in the ’90s, and it was kind of in a period where I feel like he forgot how to sing. I don’t know. Maybe because he had just gotten sober. Because when he’s on, he’s one of the great singers. I did that Velvet Underground tour, and he sort of sang like someone had just handed him the words to a song he had never heard before. I think you can get bored, you’ve done the same song 500 times so you want to do something that’s more interesting to you but not necessarily more interesting to the audience.

The solo tour Lou Reed we did, the Hooky Wooky tour for that album Set The Twilight Reeling, and again I didn’t love his singing on that tour. But then once in a while he would slip into it and do something great. I think I found more of an appreciation for his songwriting when I sat down to do a podcast for Jokermen about the Loaded album, and I just went through all the chords for all those songs and realized these are a lot more chord-ly a lot more complicated than people think of when they think of the Velvet Underground. “Oh, well this is a band that just played three chords,” and it’s like no, not true at all.

Luna Covering Television’s “Marquee Moon” (2020), Working With Tom Verlaine On Penthouse (1995)

Luna covered “Marquee Moon” by Television. How does it feel playing that song? Because I know Television was a very big influence on you, and you worked with Tom Verlaine a little while recording Penthouse.

WAREHAM: We did that cover in the pandemic, so before Tom passed away. I sent it to him and he didn’t comment on it. [Laughs.] That’s another person who people think of, rightfully, as a genius guitar player, which he is, but really it’s his singing in Television that makes those songs, those albums sound very different and unusual. That was actually an idea by former Luna bass player Justin Harwood. He was like, “Let’s do ‘Marquee Moon,'” and I was like, “You’re crazy, it’s not possible.” [Laughs.] But we did it, and for me the challenge in that was doing the vocal.

Dean & Britta’s Patreon (2021-2024) And The Indie Rock Business Now And Then

As someone who has been a part of the indie rock world, major label world too, for so long, how does it feel being an indie rock lifer? Do you feel comfortable in your position or do you feel you still have to hustle in some capacity?

WAREHAM: I have to hustle. The Patreon me and Britta did during the pandemic when nothing was going on, and actually put it on hold a year ago. It was fun but it was time consuming with three songs every month. I need to write an album, not thinking about this full time. Yes, obviously the industry has changed so much. The music business is a bunch of smaller businesses and as an indie artist you kinda have to adapt and perhaps I’m fortunate to have come of age musically where people were still buying things so my fans will still buy things. You just have to be doing more: make records, tour. People bitch and moan about the internet and how it has destroyed the music industry, but it has also provided opportunities and ways to connect with your fans like you’ve never done before. You can get your music heard all over the world much easier than you used to. Just good luck getting paid for it.

Do you like the new system, despite how time-consuming it is?

WAREHAM: I guess life was simpler when I just had to make a record and managers and publicists doing all the other work. There is a lot of social media work. Everyone says this and you have to do it. It’s a necessary part of the job. I guess we all wish we didn’t spend so much time on social media. I only got on social media when I put out my book and my publicist was like “You need to have a Facebook page.”

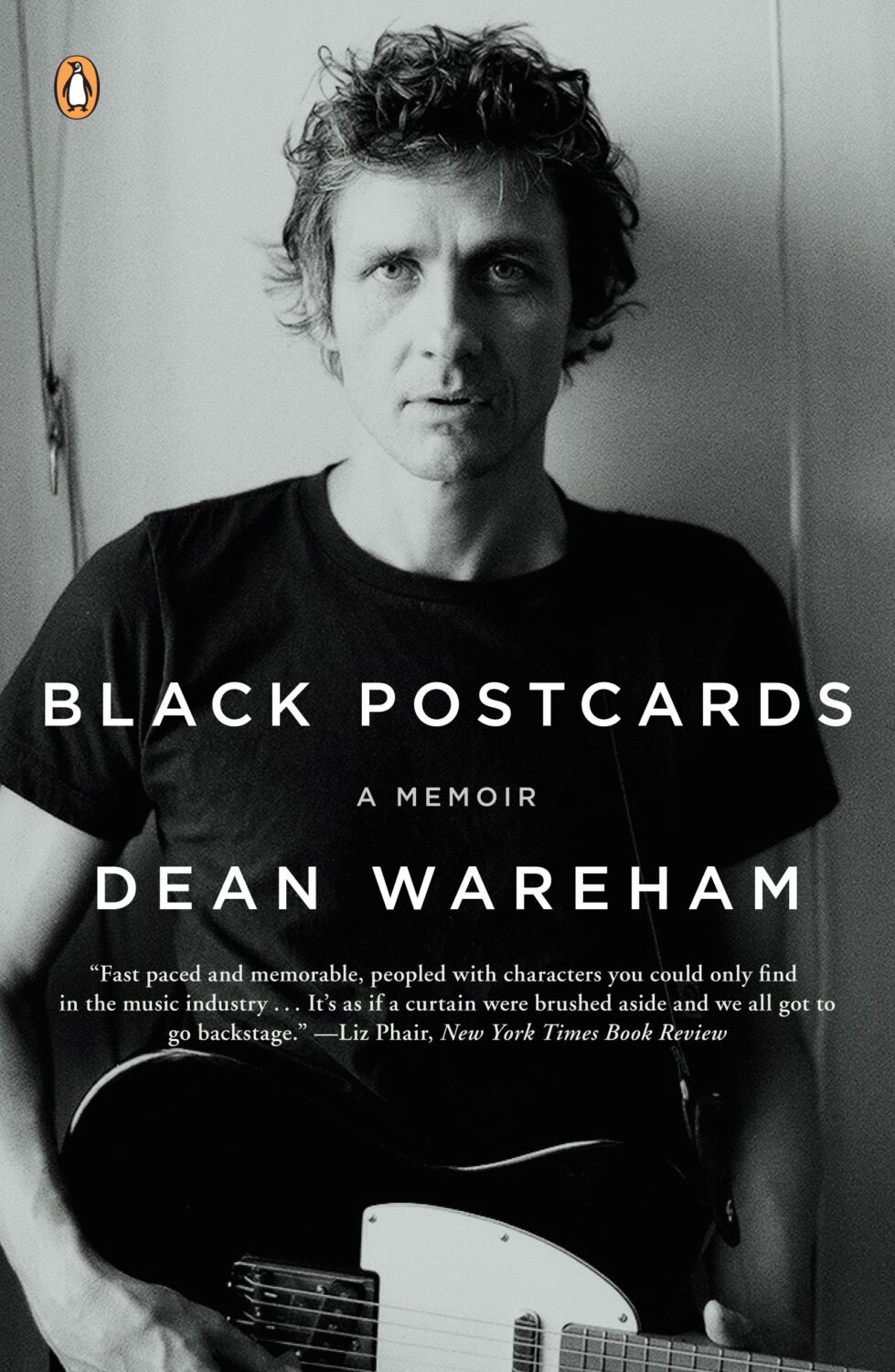

His Memoir Black Postcards (2008)

Black Postcards, your memoir, feels very ahead of its time. Because Jeff Tweedy has a memoir, Kathleen Hannah has one, Carrie Brownstein. Crying in H Mart was one of the biggest books of the last few years. How does it feel being ahead of the curve?

WAREHAM: I was ahead of the curve maybe in that when my book came out it’s like here’s a book where the musician actually wrote himself. There’s plenty of music memoirs, but usually they’re ghostwritten. So they tend to start sounding the same ’cause they’re too well written. I was lucky that someone came up to me and was like, “Hey, do you want to write a book?” Obviously the book industry is struggling like every industry is struggling. Everyone is struggling for our attention. That’s the commodity. Our eyes on the screen.

Is there anything about the book that you would do differently now?

WAREHAM: There are a few people I accidentally insulted that I would fix. [Laughs.] I did fix some things in the paperback. I remember Neil Strauss who used to write for the New York Times, he used to be the music critic. He said, “The people who get angry at you, it’s not going to be like your ex-wife or your bandmates so much, it’s going to be someone who you barely mention in passing and they see it and go, ‘How dare they say that about me!'” And he was absolutely right. Those people got upset at me about a sentence I barely thought about. “How could you be so mean to me?” and I was like did you read the book? I’m pretty mean to myself.

Cagney And Lacee’s Six Feet Of Chain (1997)

Can you tell me about forming Cagney And Lacee?

WAREHAM: I don’t think anyone has ever asked me about that. [Laughs.] That was recorded at home, and it sounds like it. Partially it was recorded by me, and I’m not very good at the technology at home. But yeah, it was a record I made with my wife at the time, Claudia Silver. All covers I think? It’s out of print now but maybe it’s on YouTube.

That’s how I heard it. Apologies.

WAREHAM: [Laughs.] I’m OK with things being on YouTube. Though I could probably put in a claim and monetize it.

Dean & Britta & Sonic Boom’s Holiday Album A Peace Of Us (2024)

You’ve been friends with Sonic Boom for years, and he even released — I guess you would call it a remix album of Dean & Britta material [Sonic Souvenirs]. But A Peace Of Us is the first time you’ve collaborated together. I was curious what that process was like and how you settled on doing a very December album.

WAREHAM: Yeah, this was the first full album we’ve collaborated on together. Mostly me and Britta recorded these things at home. He would add his own tracks and he suggested a lot of the songs. We went to mix all of the songs at his home studio in Portugal, got them all sounding good, and as we left we were like “Peter [Kember] you should sing, we should get you singing on this record.” And he’s all, “Oh no, I don’t like to sing. Maybe.” And then a few weeks later he sent us vocals for at least like 10 of the songs. [Laughs.] So then it took some time to work those into the album, and I’m really glad he did that. Sonic Boom is just a classic eccentric English artist, a genius at creating sonic landscapes from synthesizers and audio effects, a bit like Brian Eno in that respect, both very unusual musicians. And he’s not content with repeating the same formula album after album. Even in his live shows you see him really pushing the boundaries of what is possible for one person to do on stage.

That’s The Price Of Loving Me is out now via Carpark.