We’ve Got A File On You: Rhiannon Giddens

Ebru Yildiz

We’ve Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

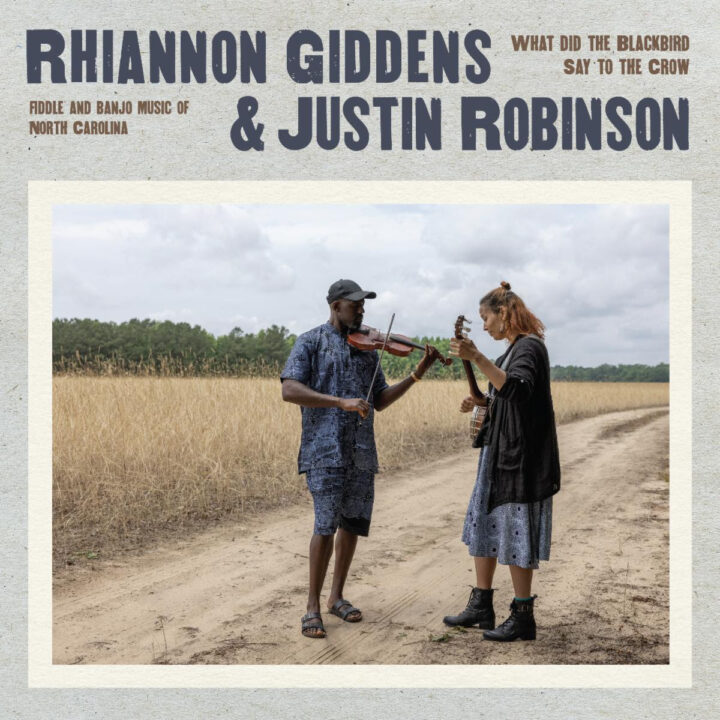

There’s a few thousand special guests on What Did The Blackbird Say To The Crow, Rhiannon Giddens’ new album of field recordings with fiddler Justin Robinson. The duo, who first played together in the Carolina Chocolate Drops, decided to record a selection of folk songs at historic sites in North Carolina. They didn’t plan it, but those outdoor sessions coincided with a cicada brood, who produced a wild buzzing throughout their version of “Pumpkin Pie,” a tune associated with their late mentor, Joe Thompson.

“We lucked out in a weird way,” Giddens says. “The cicadas would be super loud, and sometimes they would make different sounds. We just let it happen. When the music starts, the cicadas kind of retreat back, and then as soon as you stop the music, you hear it again. I love the fact that they’re on there.”

Giddens’ career is full of similar surprises and unexpected collaborations. After training as an opera singer (she recently hosted a podcast called Aria Code), the North Carolina native became obsessed with the banjo and the history of Black banjo players — a history that was largely unknown when she first picked up the instrument. In the mid 2000s she co-founded the Carolina Chocolate Drops, one of the best and most consequential string bands of this century. In addition to bringing attention to obscure folk tunes from North Carolina, they put their stamp on modern songs, including Blu Cantrell’s “Hit ‘Em Up Style (Oops!)” and Tom Waits’ “Trampled Rose.” (More recently, you heard Giddens’ playing on the original version of a modern hit: Beyoncé’s “Texas Hold ‘Em.”)

When the Drops disbanded following 2012’s Leaving Eden, Giddens launched a varied solo career that straddles opera, folk, pop, and even television. A self-professed band person, she has never made a truly solo album, but has instead collaborated closely with T Bone Burnett, Francesco Turrisi, composer Michael Abels, and Allison Russell, among others. She has gradually and steadily assembled a community of musicians who are simultaneously digging into the history of the music and presenting it in new ways and new venues. “I could never have imagined the career I’ve had. I couldn’t have put all of this together when I was 22. My mom used to tell me, We are too small to imagine all the things we could be doing. That’s why we have to focus on the thing in front of us.”

What Did The Blackbird Say To The Crow (2025)

You and Justin recorded this album at various historic sites around North Carolina. Why did you want to do that?

RHIANNON GIDDENS: I got the idea years before that we need to film and record these songs outside in the space that they’re from, kind of re-orientating the music. Not that you have to have it there, but it’s good to remind folks that all of this music came from a place. It was regional before it was global. When we started, that’s when the cicadas came. There are birds, too. All of that marks the music in a way that I think we’ve taken out of how we make art. We take all the hisses and pops that used to be on the record. We take out all of the things that really tell you what’s happening. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s not the only way it can happen. It can happen this way, too, and it did for a long time.

You recorded at the homes of Etta Baker and Joe Thompson. Baker is fairly well known outside of North Carolina, but Thompson much less so.

GIDDENS: Joe Thompson was the godfather of this whole movement. I didn’t know about him growing up. He was an African-American fiddler, and he was a connection to Black string bands. That’s a huge part of American history that we’ve erased. Another thing that he represents is the musician who has a place in their community. He was a community musician. He worked in a furniture factory. But he played with his brother in the fiddle and banjo tradition, which is very strong in the Piedmont part of North Carolina. That lineage goes back to the time of slavery and it represents a different cultural space that this music used to live in before it became a consumable product. Joe and his brother would play for what they called frolics.

When did you meet him?

GIDDENS: Me and Dom [Flemons] and Justin — the original Chocolate Drops — were at the Black Banjo Gathering, which was this thing that happened 20 years ago at Boone State University. It’s more in the consciousness now, but 20 years ago the Black roots of the banjo was still a very shocking thing to people. They found whatever elders were still alive in the Black community and Joe was one of them. He was really important on his own, and then he mentored us in that way the old timers used to do.

How’s that?

GIDDENS: You just play with them and then you have to figure out whether or not you’re getting it right. They keep playing if you’re getting it right and they stop if you’re not. And then Joe would talk about life back then. We all became a band playing with him. Dom had been playing longer than we had, and Justin and I were really early in our instruments. I was still a beginner on the banjo. I was a trained opera singer who didn’t play any instruments until a few years before meeting Joe. We learned our style of old-time music playing with Joe. I wouldn’t be talking today if it wasn’t for Joe.

Biscuits & Banjos (2025)

And now the Drops are reuniting at the first Biscuits & Banjos festival, April 25-27 in Durham. It feels like a full circle moment.

GIDDENS: That’s exactly what it is. It’s an event about cultural excavation, which is happening in lots of different ways. It’s not just about music. It’s also happening with food and literature and art. It’s not about getting famous people as headliners. It’s really about celebrating the work that people have done in those fields. The festival is the result of 20 years spent connecting to people and wanting to pull all of them into one place — 20 years of community building, really. It’s celebrating a specific kind of cultural narrative, and it’s one of discovery. It’s one of uncovering things that have been erased, which I guess we’re going to have to keep doing forever.

How does the Chocolate Drops reunion fit in with that narrative?

GIDDENS: I think we were just like, “Maybe it’s time to do this. Let’s get together and celebrate what we did.” We hadn’t really done that when the band disbanded. Justin left first, and then Dom. I was holding on, and then I ended up doing my first solo record when I was 37 years old. I figured if I didn’t do it then, I wasn’t going to do it. But it felt like this is the moment to celebrate and take stock of who we are now. There will be a focus on the original trio of me, Dom, and Justin, but there will be some other folks who’ve been a part of it along the ways, like Súle Greg Wilson, Hubby Jenkins, Leyla McCalla, and Rowan Corbett.

Sankofa Strings (2005)

This was your first band, although there was significant overlap with the Drops. Why did this band end and the other thrive?

GIDDENS: Sankofa Strings was just me, Dom, and Súle. We started a little band right before the Chocolate Drops started up. That was in 2005. We did the Richmond Folk Festival and some other gigs. The Chocolate Drops were going parallel with that for a bit, and then we realized it could be a full time thing. So we folded Sonkofa Strings. Also, Carolina Chocolate Drops was a lot easier to remember. It was in operation for about a year. It was great, but this other project won out.

Another Day, Another Time: Celebrating The Music Of Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)

You performed Odetta’s “Waterboy” as well as a Gaelic medley, “‘S Iomadh Rud Tha Dhìth Orm / Ciamar A Nì ‘N Dannsa Dìreach.” Did you choose those songs, or were you asked to play them?

GIDDENS: That show came about right when the Drops were transitioning. Dom decided to leave and do a solo thing, so I hired some new folks to join. That’s when T Bone came to me and asked if I wanted to be part of this event, either as a solo artist or with the Drops. The new lineup wasn’t there yet, so I decided to do it by myself. By this point I’d never really done anything solo. I had just done stuff with the band. I’m really a band person. I suggested Odetta because we’re talking Greenwich Village. I’m a Black person and an operatically trained singer, so let me represent Odetta as much as one can. I can’t remember who suggested “Waterboy.” It doesn’t really matter. But the Gaelic one… that was definitely me. I do this mouth music, and it’d be nice to have a traditional folk tune in there. Plus, I always like to talk about the fact that Black culture in America wasn’t monolithic. We spoke all the different language that our enslavers spoke. There were a lo of Black people in North Carolina who spoke Scots Gallic because there were a lot of Highlanders in North Carolina who spoke Scots. I find that really fascinating. When I did those two songs, T Bone was like, “Huh, maybe it’s time for you to do solo records.”

Supergroup The New Basement Tapes With Jim James, Elvis Costello, Marcus Mumford, & Taylor Goldsmith, (2014)

You were working with T Bone a lot during this time What was your working relationship like?

GIDDENS: It was great. Another Day, Another Time is what started it all, although I’d worked with him a little bit on the Hunger Games soundtrack and something for the Chieftains. He invited me to be part of the New Basement Tapes. And I did a True Detective thing. When you’re in T Bone’s orbit, you’re really in his orbit. I was there for a while, and then I moved on to do other things. He’s very masterful at putting the right people together and letting the magic happen. Rather than telling people what to do, he lets them do what he hired them to do. I’ve definitely filed that away as I’ve gone on to have other bands and produce records. Setting up is literally the most important thing you can do

What was your experience like on the New Basement Tapes?

GIDDENS: Talk about imposter syndrome. I was convinced the whole time that he was going to take out all of my fiddling. I kept thinking, “Why am I here? I don’t know what I’m doing. I’m just this little folky girl who plays banjo.” It was done live to tape, so I was on the floor with all these basses and two drum kits, and here’s me with my replica 1858 minstrel banjo. It was a really difficult time for me. For one thing, it was my first session without my baby. He had just weaned. And after being in Black string bands for years, suddenly I’m the only brown person I see who doesn’t have a broom. I’m a banjo player among all these rockers. I felt like an imposter and felt disregarded, but then, was I just feeling it? Were they actually doing this? Near the end of the sessions I realized that they were all just doing their own thing while I was just feeling whatever I was feeling. I had to put on my big-girl pants and tell myself that only I am responsible for the way I feel. It was a good lesson for me. There are inequities in the system, and people have experiences that are just not okay. But outside of that, you have to take control of how you feel and figure out what that means.

When we did “Spanish Mary,” which is one of my contributions, the engineer got such a beautiful sound out of my banjo, even though it was surrounded by all these incredibly loud instruments. I don’t know how he did it. It all moved pretty fast. I was doing a version of “Lost on the River” and was really chasing something in that song, but also feeling like everything else would keep moving if I couldn’t figure it out. Marcus Mumford helped me nail that song down, which I’ll always remember as an act of really active generosity. He took the time and energy to help me find the tune, and then we sat down and recorded it. I think it’s absolutely stunning. It was nice to go from this small folk world to this larger world and see people still doing good things.

Acting On Nurse Jackie (2014)

You appeared on an episode of the Showtime series Nurse Jackie as a square dance caller. Was that your first television experience?

GIDDENS: It was my first television set. Maybe I’d done a documentary or two by then. I can’t remember the timeline, but it was definitely before Nashville and Parenthood. I was petrified, but it was fun. It’s another situation where I was like, “Let’s just hire a bunch of my friends!” They’re actual old-time musicians who live in New York. There’s a squaredance scene happening in New York. I don’t know if they look as snazzy as they do in Nurse Jackie, though. It was weird to see all these people dancing to no music. There’s dialogue happening, so they can’t have actual music. People were just dancing to this beat. It was strange.

The thing about being the weirdo that I am is that I generally tend to pull projects that are tailored specifically to who I am, because why else would they ask for me? They like the sound of my banjo. I’m not going out looking for any of this. They’re coming to me because of the stuff that I do. This is what I tell young people all the time. You can’t imagine what your career is going to be. All you can do is just do the thing that make you joyful.

Tomorrow Is My Turn (2015)

This was your first solo album, also produced by T Bone. Did that specifically grow out of the New Basement sessions?

GIDDENS: After going through all that uncertainty during the New Basement Tapes, I wrote a song as a thank-you to the guys, and I played it for them on the last day. It’s called “Angel City.” We ended up putting it on my solo record. I was thinking a lot about Marcus taking the time to help me find that song. I was so appreciative of T Bone, but one thing that I gained from being in his world is deciding that I did not want to be in it. I loved being a part of these big projects, but I started thinking, “What do I want to do? I want to go back over to my little corner with my banjo.” I see T Bone as being at the center of this vast web. He knows so many people, and he creates all these great opportunities. I love that. I’ve tried to do that in my own little web. What are other people doing and how can I help? If you’re doing the work, I’m here for you. I’m in this place because of a combination of hard work and luck, and it’s part of my responsibility to spread that out as much as possible.

Supergroup Our Native Daughters With Allison Russell, Amythyst Kiah, And Leyla McCalla (2019)

This supergroup seems to bear that idea out. You’re bringing in these other artists — in this case, Allison Russell, Amythyst Kiah, and Leyla McCalla — and amplifying their voices.

GIDDENS: I thought, “Wouldn’t it be amazing if these people could come together?” I love setting the stage and stepping back. And they carried that project. I definitely made my own contributions, but the whole point was to give them an opportunity to say what they needed to say. And it turned out that they had a lot to say. I didn’t know Allison Russell had writer’s block before she walked in there, but then everything just opened up. We were talking about it and everybody was saying, “We didn’t even know we needed this.” I try to follow my instincts, and they’ve haven’t really led me wrong. It was also like there was some sort of vibe happening at the time that I was trying to read. We’re actually coming back together at the Hollywood Bowl in June with Steve Martin. It’s hard to get those ladies together. They all have very active careers now, which is fantastic. We haven’t been together since the sold-out show at Carnegie Hall in 2022.

How did that come about?

GIDDENS: They asked me if I wanted to do a curated night, and immediately I thought, “Can I get the girls back together?” It seemed like a good opportunity right now. There’s the activism of Our Native Daughters and the reclamation work that we do together, and then there’s the work that they do in their own realms. How can we bring all of that together again? How can we bridge one thing to another at this moment? We all love each other very much, and when an opportunity like this comes around, it’s nice that we can take it. Maybe we’ll make another record someday when things have slowed down.

Omar (2022)

You and composer Michael Abels won the Pulitzer for this opera about Omar Ibn Said, an Islamic scholar in West Africa who was sold into slavery in the United States. How was that different from working on some of these other projects?

GIDDENS: Well, it took about five years. Actually, it took a little longer thanks to COVID, but it needed the time. Working with Michael was amazing. It’s the first double composer Pulitzer that’s even been given out. I love that because collaboration is really how everything comes about. Sometimes it’s just more visible than it is at other times. Even if you’ve gone into your garret and written this music in solitude, there are still people who’ve contributed to your knowledge, who gave you money or cooked your meals or helped you with the copying. It’s all collaboration.

But you have to know what kind of creator you are. I’m someone who will have an idea percolating in my head for a long time. Then, when it comes, it comes out pretty much whole. There’s not a lot of editing that happens for me, but I’m a constant bouncer. I’m always bouncing ideas off other people. “How is this? Am I on the right track?” I just need to know I’m not insane. I have a little group of people that I send things to. I’m not even looking for criticism per se. It’s more like, “Do you feel this? Yes or no.” That’s just the kind of collaborator I am. I used to think I was a freak, but then I learned about a guy named Andy Razaf, who was a Black lyricist in Tin Pan Alley. He wrote “Honeysuckle Rose” with Fats Waller. And he said the same thing: When songs came out, they came out whole. Okay, I’m not a freak!

Is that how Omar worked? Did certain songs or arias come out whole?

GIDDENS: Man, it was nuts. There’s a moment when Omar steps foot in America, and I knew a bunch of that stuff. That’s why I took the project. I’d already done some reading on West Africa and Islam all that stuff. So it came out pretty much whole. But my style leads to mental health crises, because I live with these ideas 24/7. If I’m not getting them out, then they’re just there rattling all the time. Omar was driving me a little nuts, but at the end, it felt like I didn’t write this, especially the Middle Passage scene. I’m not a Christian person. I’m a spiritual person. I believe that there’s an energy, whatever you want to call it. I don’t’ really care about names. As creators that’s what we’re tapping into. I believe that. Sometimes I would go back and read parts of Omar and think, “Did I write that? I wrote that. Wow.” It’s not, “Oh, aren’t I amazing?” It’s more like I feel blessed that I was able to tap into something that feels like truth to people. People go see Omar and it feels like what I wrote is truth to them, and that’s all I can hope for. A Pulitzer is nice, but it’s the people who go see it, whether they’re Muslim or Christian or whatever, and feel some truth in it. That’s all I want.

What Did The Blackbird Say To The Crow is out 4/18 via Nonesuch.