We’ve Got A File On You: William Tyler

Angelina Castillo

We’ve Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

William Tyler is one of the most innovative Americana musicians of his generation. The Nashville-based guitarist found his footing as a member of bands including Silver Jews and Lambchop in the ’90s and early 2000s. Eschewing alternative songwriting in favor of folky fingerpicking, Tyler released his solo debut, Behold The Spirit, in 2010. The 15 years since have found him straddling ambient and instrumental country, dabbing in elements of krautrock, downtempo, and psychedelia. At 45, he’s honed a formula that is reverent and cinematic, allowing him to attain legend status amongst crate digging heads and purists alike.

I saw Tyler live in 2023, at the beloved Hudson Valley venue Tubby’s. That night, Tyler’s backing band, the Impossible Truth, supported his skunky Gibson SG shredding with motorik grooves. The quartet pushed Tyler’s trademark expansiveness into bluesy, climactic terrain. New-school jam band Garcia Peoples opened, cementing that Tyler is as adept at tie-dyed world-building as he is conjuring earthy atmospheres.

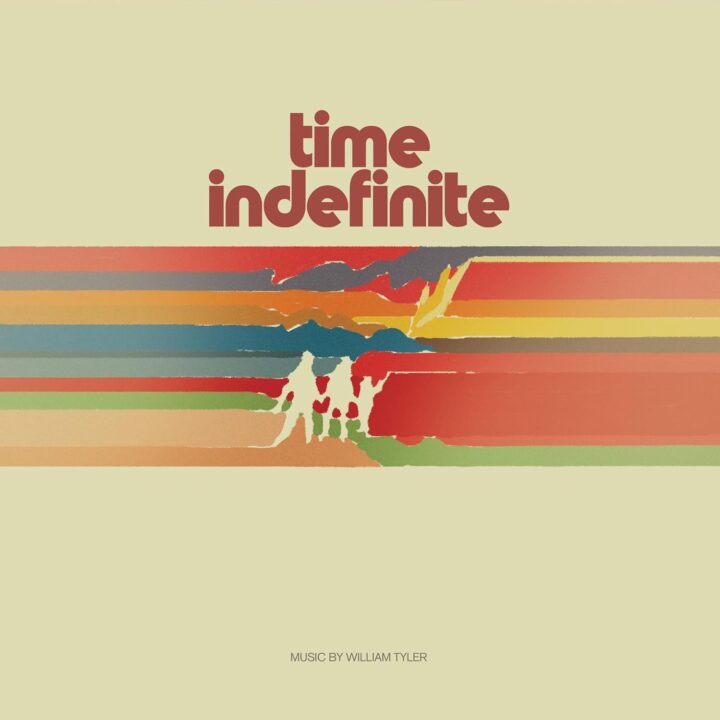

Time Indefinite, Tyler’s new full-length for Psychic Hotline, is a universe removed from his gnarled set at Tubby’s. The album was recorded on lo-fi gear as Tyler found himself stranded away from his former home in Los Angeles near the start of COVID lockdowns. The album occupies a thorny end of the Tyler spectrum, his fretwork obscured by tape loops, audio clips from home movies, and lopsided analog warbles. Tyler candidly grappled with alcoholism, mental health, and existential anxiety in the build up to Time Indefinite, and the album conveys wordless resilience.

Less than a month after the release of Time Indefinite, today Tyler is back with news of 41 Longfield Street Late ’80s, his latest collaboration with Four Tet. Coming this September via Temporary Residence, the full-length project follows the pair’s funky, Gloria Loring-sampling 2023 12″, “Darkness, Darkness” / “No Services,” and asserts that the unlikely collaborators share more common ground than one might initially expect. Also unexpected: the highly unorthodox cover of Lyle Lovett’s “If I Had A Boat” they’re sharing today along with the album announcement.

Tyler joined me over the phone, driving down a rainy midwestern freeway a day before the Time Indefinite tour kicked off. The connection faded in and out of focus, inadvertently complementing the half-lucidity that defines the record. Tyler was convivial and honest as I probed his history as a band leader, session musician, and one-time Kelly Reichardt film composer.

Working With Four Tet (2019-Present)

You just announced a new record with Four Tet and you released the “Darkness, Darkness” / “No Services” 12″ with him a few years back. That’s a really cool but somewhat unlikely crossover. How did you guys get involved?

WILLIAM TYLER: I thought it was definitely a reach. I was trying to aim pretty high, asking someone who I was a fan of, but we’re not in the same world. The way I originally pitched it to him was, “Would you be interested in producing my next record?” And of course, even with that in mind, I had no music. It was just, like, “That seems like it would be cool.” I knew that we knew enough of the same people to where I could probably have a conversation. And that’s basically how it started.

This guy Morgan [Lebus], who runs the publishing administration company that I’m signed with, used to work at Domino, so he knew Kieran [Hebden]. And this guy Kris [Chen], who works with Psychic Hotline, also knew Kieran from that era. I can’t remember who emailed and introduced us, but Kieran was, like, “Oh yeah, I’ve heard of that guy.” He was, like, “I saw him play at Bonnaroo.” Which is crazy, but I did play Bonnaroo in 2013. I guess his set had been earlier in the day and he caught some of our set and remembered that. So we set up a phone call. I was living in LA, and he was going out there pretty frequently. We’re both music heads, like, record people. He listens to a ton of music, like a lot of people in that world. Essentially, because he knew I was from Nashville, he was really interested in talking about country music — like, a specific type of Americana, singer-songwriter thing from the ’80s and ’90s. Kieran’s father, that was the kind of music he was really into. Stuff like Steve Earle and Joe Ely, and Lyle Lovett. That vein of country. I knew a lot of that stuff.

And then lockdown happened, so we weren’t going to be able to do anything in person. But through 2020 and 2021, we did kind of keep bouncing emails back and forth every couple months. I was honestly just trying to keep the lines of communication open, and would send him ideas that I thought were things he could work with. We were seriously talking about doing a record together, but were figuring out how that could work. And he sent me the track that became the 12″ with “Darkness, Darkness.” I think he sent it to me, like, “This is something I’ve been messing with, I’d love your input.” I feel like he was auditioning me or something. I sent him back a ton of stuff and of course he worked with it and it came out really cool and eventually we put it out. But in the meantime, a lot of the ideas I was sending to him were these beds of sound.

I was back out in LA for about a year and I hung out with him a couple times. He was, like, “Let’s make a record where we’re in the same room and either you play all the stuff and I’m producing or we both play and I’ll mix it.” So the record that’s coming out, that’s how we made it. We recorded it in a studio in Silver Lake in March of 2022. Considering now I’ve known him for five years, I’ve only been in the same room with him six or seven times, probably. We talk on the phone, email, text — all of that. It’s just funny that you can have that as a working creative relationship, and I consider him a friend at this point…

It was just a real slow but cool organic process. In the meantime, a lot of stuff that I thought of as being templates for stuff that maybe he could work with me on turned into pieces that were finished in a different way for Time Indefinite, my new record.

You and Four Tet are musicians I love, but I would not mention you in the same breath in terms of the music you make. What do you feel like is the middle ground between you guys creatively?

TYLER: I just think having a mutual love of all that late ’90s, early 2000s post-rock. We had a formative love of a lot of those Thrill Jockey bands and the stuff going on in Louisville and Chicago. We’re about the same age. He’s, like, two or three years older. So that probably was the middle ground. We had shared reference points for ’90s indie rock that was pretty important for us growing up.

Time Indefinite (2025)

With Time Indefinite, I really like it but it doesn’t sound like “William Tyler” to me. I think that’s probably why I like it, since it’s cool to hear you shift. Can you talk about the experiences that shaped such a different record?

TYLER: A lot of it was timing and circumstance. I guess that’s how most things take shape. I was still kind of in the middle of promoting that album Goes West. Those are mostly pretty complicated, very constant, very melodic compositions. I was very much trying to go for that, as much as any indie record I’d made up until that point. I really wanted it to be acoustic-driven, kind of in Windham Hill, ECM territory. The production was pretty slick, but because a lot of the music was acoustic-guitar-driven, it was easier to play solo. But I kind of was burnt out on that particular style. New songs weren’t really coming up in that same way. I would start things and be, like, “It sounds like this other song.” That was probably one of the reasons I wanted to reach out to Kieran.

And in then the insularity and elongation of time during those two years of the pandemic, no one was expecting me to turn a record in. I didn’t have anything lined up because everything had been cancelled. I just started going back into myself creatively in a different way. I was regressing a lot, in terms of my mental health. But I was also sitting still for the first time in, like, 10 years and feeling nostalgic in a way that felt unfamiliar. I’m so used to feeling forward momentum. It was a combination of listening to different kinds of music, like electronic and ambient stuff. And then also just getting really back into obsolete media, like cassettes and video tapes and stuff that I had lying around my parents’ house. Lockdown happened and you had a lot of time to do archeology on your personal collection of stuff. I think the somber nature of it had to do with the sadness and the depression I was feeling, frankly.

I was working very closely with this guy Jake Davis, who’s a Nashville guy who co-produced the record. When people were in their isolation pods, or whatever, he was kind of one of my peeps in that pod. We would get together once or twice a week and mess around with stuff, record different ideas. At some point like a year later, I was back in Nashville visiting. I can’t remember what song it was, but I was like, “I think this is going to be a record.” Which is interesting because I had mostly done records in a pretty traditional way, where you go into a studio where you booked five or six days of time and do it as quickly as possible because you don’t have the budget to do it otherwise. That’s how Impossible Truth, Modern Country, and Goes West were all done. I got back into home recording during lockdown, and having the ability to do things slowly and not with any clear purpose was just a different way of writing and composing.

What was it like pivoting from jammy guitar riffing to tape loops?

TYLER: It’s fascinating. It’s not something I would have come to by myself. It’s very much because I was collaborating with Jake. And Jake’s the one who actually figured out how to make physical tape loops. I had always been interested in textural things that were out of place, not quite in focus. I like decay. I don’t like music that’s super clean, even though I’ve made quite a bit of it. I’ve always liked using pedals and looping, and this is kind of a more organic, analog extension of that process. I feel like that stuff used to be in the background of all of my records, but this time that was the main character. And the guitar was not the main character. Maybe, like, a narrator or something. But not the star.

The liner notes and your social media have talked pretty candidly about struggles with addiction and the general pain of day to day life in 2025. With this record out in the world, how do you feel like these vulnerable themes translate through the music?

TYLER: There’s a seeking quality to the way the music comes across that I think is in line with the dark night of the soul, for lack of a better term. There are some very purposely pretty moments, and they’re kind of there to break up the dissonance. The word “hopeful” has come up a lot in conversation, or in some of the reviews I’ve read. I can’t say that the record, to me, felt hopeless. But it certainly didn’t feel hopeful. Maybe it felt manic. I think the actual word nostalgia means something like homesickness. The concept of nostalgia, as it originated, whenever it did, probably in the 19th century, was definitely about a really melancholy type of remembrance — a longing. I think that’s where a lot of the more melodic, consonant moments come from. The world got quiet and there was kind of a heaviness to it. I think there’s some tracks that I wanted to be, pretty literally, representations of what it feels like to have a mental breakdown or something close to that.

Debut Album Behold The Spirit (2010)

After so many years of playing in other peoples’ bands, what was it like working as a band leader for the first time?

TYLER: It was exciting to be working on my own music in a real studio. It wasn’t the first time I’d ever done that. I always did a lot of home recording, but the way we made that record was that my friend Adam engineered the record. He worked at this recording studio in Nashville that, during the day, made very commercial country music. When there was dead time, we would go into this particular studio and work on stuff. That’s how that record took shape. I think I was starting to have an identity to the kind of guitar music I was playing and writing. I wanted to make as confident of a statement as I could with that. I didn’t even really know if it was going to be released or who would put it out and who would listen to it. I didn’t have any expectations.

With Josh at Tompkins Square, we had been corresponding about some other thing and had mutual friends. He was one of the people I sent the record to, and was like, “Oh yeah, I want to put this out.” And I was, like, “Well if he wants to put this out, this is actually going to get into different peoples’ ears.” That’s how that record took shape.

In 2010, instrumental music with this much heart wasn’t quite as common as it is today. I feel like you helped carve a bit of a path for, lacking a better term, the whole cosmic Americana thing. How have you observed the experimental country landscape evolve since your first record came out?

TYLER: It’s kind of funny. The two genres I’ve had associated with my music are Americana — which is a pretty broad term at this point — and new age, which is also a pretty broad term. And they’re both terms that a lot of people in those genres sort of recoil from. The other day, I saw somebody post something, like, “Ambient Americana needs to be stopped.” People are already sick of this microgenre that has, like, zero cultural impact. That’s like saying marching band music must be stopped. Like, not really!

I didn’t have role models per se. I was a fan of a lot of people who had done that kind of music, specifically Jim O’Rourke — he was kind of the big one for me, always — and Six Organs Of Admittance. But you’re right, it didn’t seem like something people my age or younger were doing. James Blackshaw was doing it, but I felt like he was already starting to step away from it at that point. I do think that there was an aspect of me being on a label like Merge and then me having a history with more mainstream indie stuff, like Silver Jews and Lambchop, specifically. There were a lot of things that lined up to where people that wouldn’t have necessarily been exposed to that kind of guitar music were. I do think it makes sense now that you can see people like Hayden [Pedigo] and Daniel Bachman and a lot of guys who are 10 years younger than me, it’s nice to see there be more of an intersectionality of a pretty underground kind of music with overground type bands.

Modern Country (2016)

I love Modern Country. To me, it kind of feels like the quintessential William Tyler record and also, true to its title, has the most immediate country influence. I’m curious about how you molded Western traditions to a more modern musical template.

TYLER: Once again, Jim O’Rourke has always been such a big reference point. Specifically when he married the fingerstyle guitar music with orchestration and more classical studio arrangements. I thought that was really fascinating. But I wanted to do a version that was a little more indebted to krautrock and German ’70s stuff. So the approach with that record was trying to find some commonality between country music of a specific time, like the ’70s, with music that was being made in Germany at the same time. Both genres are really good driving in the car or truck music. I wanted to really lean into any similarities you could. And most of the reference points on Modern Country are really specific to German stuff of that time. Or to stuff that was going on in America, like Waylon Jennings or Ry Cooder.

Using the phrase Modern Country as the title, I couldn’t believe nobody had used it yet. In Nashville, I don’t think they even use that term anymore. When the record came out, that, specifically, was referring to Top 40 country music of the time. But of course, I was using it as more of a term about where the United States was at. And it came out in 2016, but it came out before the election. But I was hearing a lot of sadness and decay in it, because I was so convinced that we were about to go through a big, big depression. And of course, we did and still are. So there was a lot of social commentary within it.

It was also written in a period after I’d been touring mostly by myself for the first time and driving across the country, through rural parts of America, and taking in the geography and the vastness of the differences between parts of this country and how they bleed into each other when you’re on a road trip. Those were the spiritual reference points.

Lost Futures With Marisa Anderson (2021)

Lost Futures was the first record I heard from you. I feel like, for me, it was a pretty perspective altering one. In spite of people currently dumping on the whole Americana, instrumental thing, I loved it. It was over COVID and I was living in Los Angeles, so it really hit the spot. What was it like working with Marisa Anderson to bring that one to life?

TYLER: It was interesting because I hadn’t collaborated with anyone that closely in any way with that kind of music. I’m used to collaborating with people where someone brings in songs and you play behind them as a session musician. She brought in a couple ideas that were already fleshed out, but she didn’t know how to incorporate them into her solo stuff. And I had a couple things that were, similarly, songs that I just didn’t know how to…

A lot of it, we wrote just jamming together over the course of a week in Portland. This is when lockdown was still going on. The window opened for people to travel a little bit, and I flew to Portland and hung out with her for a week. We just played guitar. We had been sending ideas back and forth, and we got together and jammed for three or four days. And then we spent another three or four days recording. It was a weird time. It was in the middle of all of the protests and wildfires and imminent election and seven or eight months into lockdown and people were pretty fatigued, spiritually and emotionally, from that. We had a very intuitive way of playing together. We had only played together a few times before deciding to make a record. I think she was the one who introduced the idea, so she must have sensed that there was some kinship.

It ended up being that we had so many weird idiosyncratic things that we share interest in, like, specifically history and obsolete technologies and the same kinds of old movies. Stuff that you can’t necessarily instill into a guitar instrumental, but we kind of have commonalities on all those things. And that helped it be a really organic creative process.

Scoring Kelly Reichardt’s First Cow (2019)

You and Kelly Reichardt make a ton of sense as a pairing, and I’m curious how you ended up working with her.

TYLER: She was already editing the film, so it was pretty close to being done. She was looking for a very specific type of sound to fit that movie because it was a period piece. She wanted something really sparse — a version of folk music that didn’t necessarily sound particularly tied to any era or geography. That’s kind of hard to put your finger on. My name came up. We have a bunch of mutual friends, mostly in music but actually some in film.

I got kind of lucky, honestly. I think she was at the point where she was making really decisive moves finishing the movie. I sent her an audition reel with demos, or whatever. Her assistant editor sent me a link to the cut they were working on. And what I had already sent her was in the film as temporary music. So I was, like, “Oh, okay. She really wants to get this done.” I worked really closely with her. She edits her own movies, so she’s, like, incredibly specific about timing. I’m sure directors who don’t cut their films are, too, but she really is the one doing it. The way notes line up with frames, if she had wanted music that was a lot denser and more complicated, I don’t know if I could have pulled it off.

There wasn’t a lot of time to work with, and it wasn’t a huge budget to work with, either. It was pretty much just me and another buddy out in LA who had a home studio, and I think we brought out one other musician. The reference points she had were things like Bruce Langhorne and Washington Phillips and some of the other folk music that gets on those compilations Mississippi Records puts out — the stuff that sounds really weird and out of time. I don’t mean out of tempo, but just out of any sense of modern or ancient or whatever. So that was a very specific direction she wanted me to follow with the music.

Was this your first time scoring a movie, and how did you approach it?

TYLER: It was the first time. It was intimidating because she’s such a renowned filmmaker and I was a fan of hers. At this point, I’m probably more interested in film than music. I had done quite a bit of playing and live scoring with other musicians, and getting a sense of timing and studying the way the soundtracks that I really like work. I feel like I had a good backlog of knowledge about how I wanted to work with it. But really, honestly, everybody’s so different in their creative process when you’re doing that stuff that I was, like, “Okay, well, as long as I don’t fuck this up.” It’s very minimal in the film, so it’s not, like, Hans Zimmer. It’s not dense music. It kind of felt like the music shouldn’t be what you’re noticing first. It should be how it plays with the image.

Sometimes they become very linked, and that’s why certain pieces of music in certain songs, I think in popular culture, are going to be forever linked to the way they were used in a particular film — for better or for worse. If you’re aware of films that have been made in the last 50 years, you’re not going to be able to hear “Stuck In The Middle With You” and not think about someone getting their ear cut off. Pretty extreme example, but you know what I’m saying.

Working With Backing Band The Impossible Truth (2013-Present)

When we met, you were on tour with the Impossible Truth, and I really loved your set at Tubby’s that night. But it also felt super different from your album stuff. What was your process like for assembling that band and who all was playing in it?

TYLER: The band has changed over the last 10 years. The first time I put a version of it together was that weird, alternate universe that actually happened where I got asked to play Bonnaroo. And at the time they were, like, “Can you play with a band?” I was, like, “I’ve never done this with a band, but I’m sure I can.” Luke Schneider, who plays pedal steel, has always been in whatever version of that band. Brian Kotzer, the drummer, we go way back in different ways. We were both in Silver Jews together, the live version of that band. So I’ve been friends with him for the last 20-something years. And then Jack Lawrence, who plays bass, was kind of the guy I didn’t know as well. But we had lots of mutual friends and had always wanted to play together.

As far as arranging things, there were only a few songs that we played in the live set that I wrote specifically for a rock band. Most of the other stuff are songs that have already been on records of mine that we slightly rearrange. It’s a really fun project, especially being able to A. play really loud and B. actually improvise and go out into some territory. We did a bunch of tours. There were definitely a lot of people at those shows where, like, they wouldn’t necessarily have come to see me play solo. The dudes in a rock band concept, there’s been so much of it in the last 60 years that it’s, like, there’s nothing new you can do about how to present it. But I will say that not having a singer makes it more democratic. There’s not, like, a lead thing. It really is four people playing together. I didn’t have to be on top of the beat all the time. I could lay out and I could let other people play. It’s really different from the way that I play guitar when I’m playing solo.

I just went to Nashville for the first time, and I liked it more than I thought I would. But the city had a real “country music politics” vibe, from what I could tell. I’m curious how you approached assembling a Southern-fried but pretty weird band in a city that seems to gravitate towards normalcy.

TYLER: Well, there’s always been a community of people in Nashville that like weird music. It just always existed very much on the margins of what was going on. But since it is such a music business, industry type of city, not me so much, but a lot of people who play all different kinds of music do work professionally in that world of country music you’re talking about. It keeps it pretty conservative, I will say. The city’s gotten a lot bigger and more appealing to certain types of artistic people, so there’s a lot more interesting stuff going on in all of the underground scenes — visual arts, music, film, theatre, whatever — that wouldn’t have been there 15 years ago. But as far as overlapping with people who work for major labels, it doesn’t exist. In an interesting way, much more so than I would say in Los Angeles or New York, probably, although I’ve never lived there before.

You know, it’s a very conservative city. When you said “country music politics,” I didn’t know if you literally meant politics of music. But it’s become sort of a magnet for right wing politics.

I was more thinking about just the hierarchy of music. But I didn’t think about the fact it is a more conservative city than other music meccas.

TYLER: It’s weird. I noticed it more when I moved out to LA for a few years, and then when I came to visit and I’d go to my neighborhood coffee house and it’s, like, Trump stickers on cars. Like, “Okay, Republicans have found out about espresso and kale.” As much as everything is getting more expensive and more congested, the thing I’ve noticed about Nashville changing over the last 10 or 15 years has been just the politics. The type of people moving here, in terms of politics or corporate stuff, has gotten a lot more extreme in terms of conservatives. But, having said that, we just elected a guy a year ago that’s probably the most liberal mayor we’ve ever had. I don’t know what he is now, because once you get elected it’s hard to keep being radical. There’s still that aspect of Nashville that’s kind of a bubble in a very, very, very red circle of the state.

Playing In Lambchop (1998-2010)

It seems like you joined Lambchop as a pretty young dude, and I’m curious how that happened. What were you doing before joining that band, in terms of being a musician and also just being a young adult?

TYLER: I was aware of Lambchop in high school because there was an all ages venue called Lucy’s Record Shop that Mary Mancini, Kurt Wagner’s wife, owned and ran. Since it was one of the only all ages places in Nashville, it got a lot of interesting shows. Whatever connection Nashville had to the ’90s indie rock world, that and Lambchop were sort of the hubs. I was playing in a band, and we got signed to a record deal in high school — wildly different kind of music, like, power pop. In the interim, I didn’t go to college and I stayed and got a job and moved out of my parents’ house and just started falling in with older musicians and hanging out. Like, having some interesting formative experiences with all these people who were, like, 10 to 20 years older than me. And that was how I met the Lambchop guys.

As far as how I wound up in the band, I really think it was more just that Kurt and some of the other guys in the band thought it would be amusing to have a really young person in the band. Like, a pirate ship and I’m the young stowaway. For the first year I was in the band, I played the keyboard. And I don’t really know how to play the keyboard. That was a weird thing to fall into, but what was weirder is that I stuck around and got more involved and had my first experiences touring — going overseas. It changed my life. It’s one of those things where you can’t really imagine where your life would have gone if you hadn’t done that or been given that opportunity.

Playing In Silver Jews (2001-2009)

How did you fall into playing with Silver Jews? What was that experience like?

TYLER: It was a lot of different things. I met David the same way I met all those guys in Lambchop: just hanging out, being at bars, playing with different people. It was one of those things where it was a series of circumstances where he already had all the songs and he was gonna make Bright Flight with the American Water lineup. And then I don’t know what happened, but Malkmus decided not to be involved or something. Obviously I was not, like, his replacement, but there was something about the way that I played guitar that he liked. That was my experience. And I got to be pretty good friends with him, but he didn’t play live or tour very much.

One day he decided he wanted to do a 100% full-on live version of Silver Jews. And once again, I think they asked Stephen Malkmus and he didn’t want to do it. First Cow was similar — Kelly talked to Stephen about doing the music for it before it got to me. I owe Stephen Malkmus a lot of things that he turned down.

But that version of the Silver Jews, we were very, very close friends and stayed very close friends once David stopped touring. Which isn’t always the case with these kinds of situations. It was weird in a cool way because the first time we went out on tour, people were understandably so excited to see the songs live. I think it almost felt like what it feels like when you’re in a cover band, where you already have the audience on your side before you even play one note. The experience of being in a band like that, where you weren’t a cover band, is very fun. Different than Lambchop. There was always a sense of, like, “Oh, I don’t know man, they might not like the new stuff.” Silver Jews was very joyful, very chaotic. Everybody in the band had different degrees of neuroticism. Lots of people with master’s degrees wanting to talk to you after the show. That was the closest I got to going to college.

Do you have any favorite memories or stories from working with David Berman?

TYLER: I would say, more in general, he was not a musician and he wasn’t someone who had ever toured before. His experience of being in a band was mostly playing in a garage with your college buddies. So there were so many things about touring that I think he took for granted — mostly bad things. The drives, staying in weird motels. He would be incredulous about a lot of it in a way that was refreshing because it was, like, “Oh yeah, right, he never did this. This is actually what this is like.” It would be like somebody who hadn’t flown for the first time dealing with airport security. Like, “Why do we have to take our shoes off?” It was kind of refreshing. The conversations were always very interesting, and most of the time not about music — philosophy and poetry and politics and stuff like that.

Time Indefinite is out now via Psychic Hotline. 41 Longfield Street Late ’80s is out 9/19 via Temporary Residence.