A Composer Breaks Down The Music Theory Behind Doechii’s Hit “Denial Is A River”

John Jay

Making music is a form of therapy for Doechii. Rather than crafting songs that fit current pop-music expectations, she writes deeply personal stories and performs them as catharsis. Unlike other artists in the same space, her goal isn’t to have a song blow up on TikTok. (While that may be a splendid outcome, it’s merely incidental to her process). She described “Denial Is A River,” her biggest single to date before the Gotye-sampling “Anxiety,” as “an inner dialogue that I’m having with the voices in my head.” Perhaps to her own surprise, Doechii’s authenticity has thoroughly resonated with her peers, resulting in her recent Grammy win for Best Rap Album and in the high praise she’s received from the likes of Kendrick Lamar (who called her “the hardest [rapper] out”).

Channeling late-’80s/early-’90s boom-bap aesthetics, Doechii’s music celebrates the Golden Age of hip-hop, but it also augments it (and occasionally subverts it) to forge new, innovative paths in the artform. Let’s dive in to “Denial Is A River” to explore how the song works.

Making Beats

One of the central hooks of the song involves the recurring chord pattern in the rhythm track, underpinning Doechii’s rap verses. It comes from producer Ian James, who created it two years ago and posted it to his YouTube channel, calling it “MF DOOM Type Beat – ‘Golden’.” He formed an ostinato (repeated musical phrase) featuring nothing but “dominant-13” chords. The way the chords relate to each other is fascinating (and we’ll get to that later), but first let’s explore how James came to choose the dominant-13 flavor in the first place. It started when he sampled and pitch-shifted the chord from a circa-2000 DJ Paul Nice 45-rpm single.

Unable to clear the sample in time, he was forced to replay the dominant-13 chord using MIDI. This raises the question of why he didn’t just play the chord himself in the first place, but there are more salient questions to examine here. For instance, why does this particular chord, and the resulting sequence, sound so alluring? What are the chords actually doing, and why does the chord progression interact so perfectly with Doechii’s vocal performance?

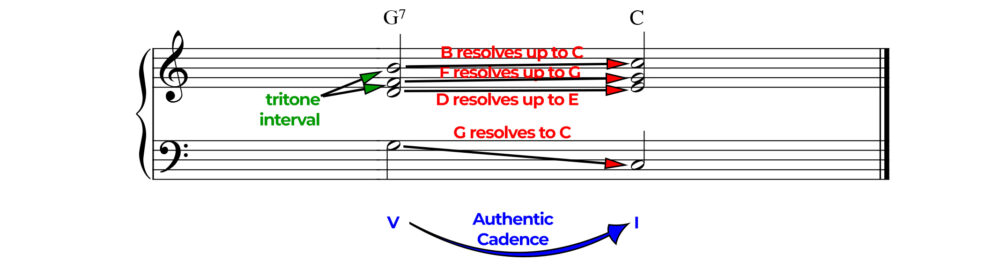

In previous In Theory articles, we’ve explored the concept of “functional harmony” and how dominant chords feel highly unstable, craving resolution. Music theorists Benward and Saker trace this concept back to early Baroque composers, and specifically to Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643). The V (“five”) to I (“one”) authentic cadence is an archetypical scenario in this framework. See Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: An Authentic Cadence in C Major, Showing a V-I Resolution

In jazz tunes, we commonly find that all the chords contain at least three notes, the essential chord tones comprising what we call “shell voicings.” These notes include: the chord’s root, which functions as a kind of harmonic anchor; its 3rd, which tells you if the chord has a Major or minor quality; and its 7th, which indicates the chord’s “intention.” If it’s a Major 7th (or sometimes a Major 6th), the chord’s intention may be to stay at rest (because it’s probably “home”). If it’s a minor-7th on a Major triad (creating a dominant-7th chord), it generally wants to resolve its innate tension. Again, see Figure 1 above. (In previous In Theory articles, we discussed tension and release characteristics of diminished, augmented, and suspended chords — topics we need not cover here as they don’t relate to Doechii’s “Denial Is A River,” but they’re fun to explore nonetheless.)

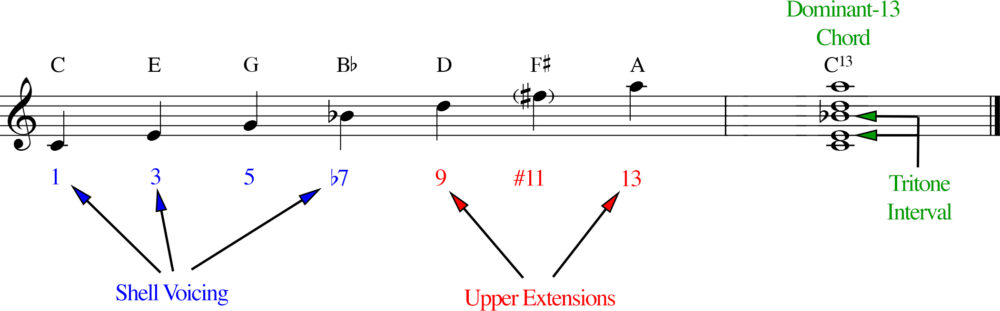

Often in jazz, we include “upper extensions” when voicing chords, imbuing the chords with additional color and charm. These extensions commonly include the 9th, 11th, and 13th notes. They can be “altered” (sharpened or flattened) or “unaltered” (natural). See Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Chord Tones and Extensions Comprising the Dominant-13 Chord

The dominant-13 chord possesses an unstable sound, seeking resolution principally due to the presence of the flatted-7th combined with the natural 3rd — resulting in the dissonant-sounding tritone interval. Additionally, the presence of the 9th and 13th infuses the chord with a kind of jazzy sophistication — a somewhat relaxed sound that still possesses a feeling of eager anticipation. (As we see in Figure 2, if the chord also contains the 11th, that extension really should be raised a half step — making it a #11 — to avoid an unsatisfying harmonic rub.). We can easily understand why James and Doechii would be drawn to this sound, as it’s redolent of the early-’90s hip-hop era when jazz and soul record samples permeated the scene. You can hear dominant-13 chords throughout the genre. A great example is De La Soul’s “The Bizness.”

To reference the sound of the dominant-13 chord in a jazz standard, check out “Killer Joe” (1960) by the great tenor sax player Benny Golson (who passed away recently). The song’s head (thematic melody) oscillates between one bar each of C13 and Bb13 (the I chord and bVII chord) with a passing half-step B♮ bass note in between. As we’ll observe below, it’s a pattern that shares crucial characteristics with Doechii’s “Denial Is A River.”

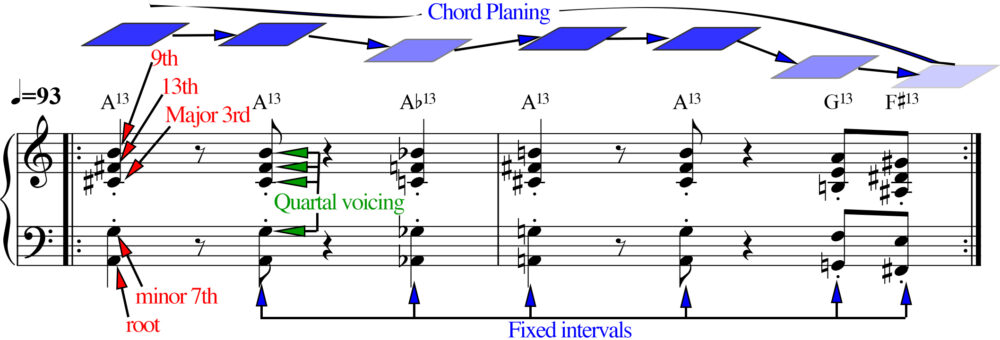

Planes Aren’t Just for Flying

The real magic in the rhythm track of “Denial Is A River” lies in how Ian James moves the dominant-13 chord around. It starts with an A13 in spread voicing — meaning it employs wide intervals, resulting in a chord that spans more than an octave. Then, he engages a compositional technique called chord planing to generate the other chords. Also known as harmonic parallelism, chord planing is quite simple: Take the exact shape of a chord (holding all the intervallic relationships constant) and simply transpose the entire group of notes up or down by a fixed amount. Don’t worry about forcing individual notes to conform to a given scale. Just move the whole bunch together and embrace whatever “accidentals” present themselves. Or, if you play guitar, imagine fretting a barre chord and replaying it higher or lower on the neck without disturbing the shape that your fingers make to form the chord. It’s not necessary for the other chords to be “in key.” In fact, it sounds more hip if they’re not in key. That’s planing. Figure 3, below, shows how “Denial Is A River” uses this technique.

Figure 3: Chord Planing in "Denial Is A River"

Chord planing is attractive as a musical device because it allows composers to produce a complex harmonic sound with very little effort. Debussy’s The Sounds And Fragrances Swirling Through The Evening Air contains several instances of chord planing. John Williams uses this technique extensively in his film scores, often planing simple triadic chords over a pedal point (fixed bass note). Check out the Superman theme and the Star Wars “Rebel Fanfare.” Williams’ use of this technique has the effect of rooting the parallel chords in a specific tonality even though the progression goes outside of traditional harmonic constraints.

And this is the crucial point: The appeal of chord planing is that it allows you to transgress, smoothly and gracefully, the boundaries of diatonic harmony (the notes and chords that belong to a given key center), without having to worry about usual chord functions or common-practice counterpoint. In traditional Western harmony, orchestrators or performers often re-voice chords to preserve notes shared between adjacent chords for smooth voice leading. But the sound of planing has become its own distinctive style. You can hear it throughout the modal jazz canon — in the music of Miles Davis, McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, the list goes on.

Chord planing became a staple of early electronic and rap music, in part due to the kinds of production tools available to producers and artists at the time. A number of synths in the ’80s (like the Korg Poly 61 and the Memorymoog) had “chord-memory” functions, where you’d play and hold a chord and then press the chord-memory button to “memorize” the chord. After this, hitting any single note on the keyboard would play back that chord and transpose it up or down depending on which note you hit. Voila! Instant chord planing. Back in the day, producers working in house and rap music made a lot of tracks this way. With today’s DAW technology, you can do this simply by recording a chord in MIDI, copying it, and dragging it up or down in the piano roll view. In fact, this is precisely how James used Ableton Live to construct the vintage hip-hop chord-planing sound in “Denial Is A River.” (See Figure 4 below.)

Figure 4: Chord Planing in "Denial Is A River" using Ableton Live

Now, this raises the question: Why did he land on those particular chord locations when planing the A13 in the piano roll? Is there something special about those locations? Let’s explore further.

Ambiguity Abounds In A

The chord progression in “Denial Is A River” is especially peculiar because it’s so harmonically ambiguous. Do the chords serve any kind of harmonic function? This may be the first article in the In Theory column where I can’t tell you definitively what key the song is in. (More on that later.)

We’re all familiar with the four-chord-loop architecture that characterizes so much pop music today. In his book Everyday Tonality, musicologist Dr. Philip Tagg describes a novel approach to understanding four-chord loops in pop music. The “Denial Is A River” progression does indeed cycle using four chords — but what’s going on here is entirely different than what we’re used to hearing. As we’ve discussed before, a core principle of functional harmony is the idea that chords within a progression have pre-defined roles to play. Each chord performs some specific job in telling the musical story. Often, this involves harmonically volatile dominant chords resolving to the resolute tonic (the V-to-I cadence), like an object being pulled towards Earth by the strong gravitational force. In “Denial Is A River,” where’s the I chord? What is the tonal center of gravity?

If we think of the song as living in the key of D Major, then the A13 chord functions as the dominant V chord. In this case, we never actually hear the I chord in the song, and the progression merely lingers between the V and the bV (the Ab13), eventually moving down to a chord built on the 4th scale degree (the G13) and then one built on the 3rd scale degree (F#13). If the progression were diatonic, the G13 would be some flavor of GMaj7 and the F#13 would be some flavor of F#min7—and the whole concoction would taste a bit bland. (Mercifully, chord planing in this song has liberated us of from those diatonic constraints.)

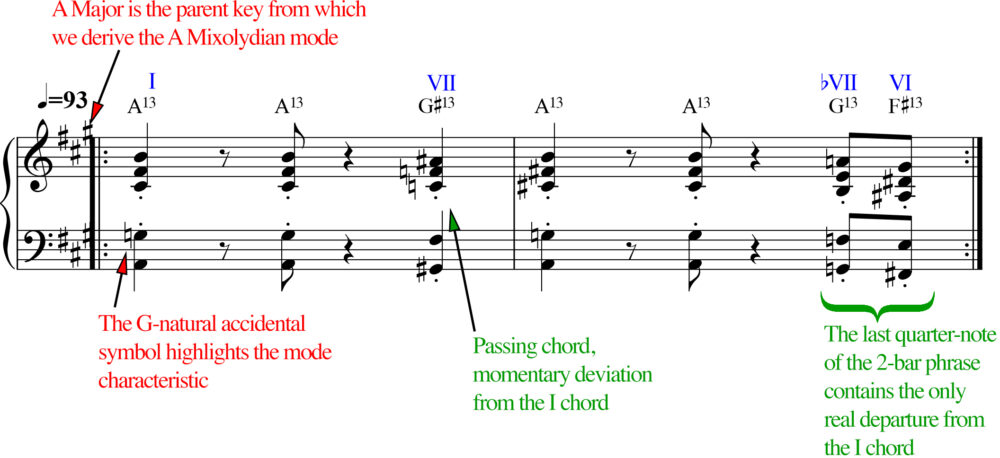

And what’s the Ab13 actually doing here? We could think of it as a passing chord, something we commonly find in jazz, where a dominant chord built on the bV lubricates the path momentarily between the V and IV chords. But in “Denial Is A River,” the Ab13 serves more as a sonic diversion while we linger on the A13. Perhaps in Schenkerian analysis, this would fall under the rubric of “prolongation,” extending the listener’s anticipation by hovering on/around the dominant V chord. If we accept this premise, then consider that the entire progression acts as prolongation — which, frankly, is how it feels. We’re eternally “waiting for Godot” — even if we suspect he’s never going to arrive. In this way, I don’t think we can consider the “Denial Is A River” chords to be governed by any functional obligations at all. Indeed, we can better characterize the entire affair as one based in modal harmony, in contrast to functional harmony. See Figure 5 below.

Figure 5: Modal Harmony in "Denial Is A River"

My best answer to the “What key is this song in?” question is… (drumroll please): A Mixolydian. That is to say, it’s based on the collection of notes we associate with D Major (Ionian), but it’s centered on A. Think of an A Major scale with a G♮ replacing the usual G# as the 7th scale degree. All the accidentals we hear (outside of A Mixolydian), like G#, A#, C♮, D#, exist in the cracks between our scale tones and they serve as attendant diversions to perk up our ears and keep us engaged.

It’s important to recognize that while we often think of key center as some objective fact, it can be open to interpretation. Carol Krumhansl, Professor of Psychology at Cornell University, has written an important treatise on this topic. The subjective nature of determining what key a piece of music is in might have to do with a listener’s cultural background or listening habits. You may hear “Denial Is A River” differently than I do. If you think it’s in B minor, that’s valid. Neither of us is wrong.

But given that I’m the author of this article, I’ll take a stand and declare the A13 as the I chord — our harmonic center of gravity. The A13 doesn’t need to resolve anywhere. It’s not a stop along a route to some destination — it’s the destination itself. While the chord may feel restless, it is, indeed, home.

As the 2-bar phrase in Figure 5 cycles repeatedly, we remain in a perpetual state of anticipation, marinating in unresolved (albeit harmonically rich) tension because the dominant-13 chords never pull us in any particular direction. There’s no sense of finality or conclusion — and I think that’s the point: to exist in limbo. I imagine this is why Doechii chose this beat for “Denial Is A River.” The chord progression is colorful but non-directive. It’s the perfect harmonic bed over which Doechii’s rap flow can dictate direction and meaning. The chords serve to create one continuous mood—a playful sense of expectation—but they don’t engage in an actual linear narrative. That job belongs exclusively to Doechii’s rapping.

One more thought to close out this topic, before we get to Doechii’s rap flow: NYU music professor Ethan Hein has postulated that any series of chords, no matter how arbitrary or incoherent, can sound “correct” if accompanied by a satisfying breakbeat drum loop. By extension, rapping over any chord loop, even if the chords were chosen at random, can legitimize the loop. (I’m reminded of Adam Neely’s “repetition legitimizes” refrain, which he got from Dave Johnson at Berklee.) When referencing “Denial Is A River” specifically, Hein suggests the chords are arbitrary, implying that any other harmonic choices would’ve worked just as well. While I think there’s merit to his argument in the macro sense, I don’t agree in this instance based on my analysis above. The “Denial Is A River” chords invoke a specific, carefully calibrated mood. That mood informs Doechii’s rap flow, which in turn imparts color and texture to the chords and drum beat. There’s a symbiotic relationship between the two. Even though they were created separately, they sound inextricably linked.

Denial Is A River, And Surely It Flows

Rap flow can be an elusive concept, but I attempted to define it comprehensively in a previous In Theory article about Kendrick Lamar’s “United In Grief.” In short, “flow” is the way a rapper converts speech phonemes into music. Hip-hop possesses a unique characteristic within the range of what we call “pop music,” insofar as lyrics play a structural role, not merely a complementary role. The sounds of the words — the phonemes, their stresses, cadences, inflections — convey musical meaning in the same way a plucked string does, or a vibrating column of air making a pitched sound. A paper published the journal Language And Speech in 2019 (by hip-hop linguist Steven Gilbers, neurobiologist Nienke Hoeksema, et al.) constructs the analogy that flow is to rap what prosody is to language. In essence, flow is a rapper’s art of delivery using rhythm, articulation, and melody.

Doechii wrote “Denial Is A River” in strophic form — meaning, it uses a repeating verse structure with no chorus or “middle 8” section. We can think of the syncopated breathing section at the end as a kind of coda, but the song still follows a kind of “AAAA” format with no “B” section. Her dexterous and varied flows reveal Doechii to be an accomplished student of the art. We can hear influences from Busta Rhymes to MF DOOM to Nicki Minaj. Her rhythmic pocket is tight, with clear diction and every phoneme pronounced with intention.

In a paper titled “On The Metrical Techniques Of Flow In Rap Music,” Kyle Adams, Music Theory department Chair at Indiana University, describes flows based on articulation and meter. He describes “articulative techniques” as ways rappers vocalize words (e.g., legato vs. staccato); and he describes “metrical techniques” in reference to when the rapper vocalizes them (placement of rhyming or accented syllables, the number of syllables per beat, etc.). Specifically, with metrical technique: derivative flow is a type of construction where the rapper derives the timing of their syllables from the metric subdivisions of the beat they’re rapping over. In contrast, generative flow is a type of construction where the rapper’s vocal rhythms don’t necessarily correlate to the underlying beat.

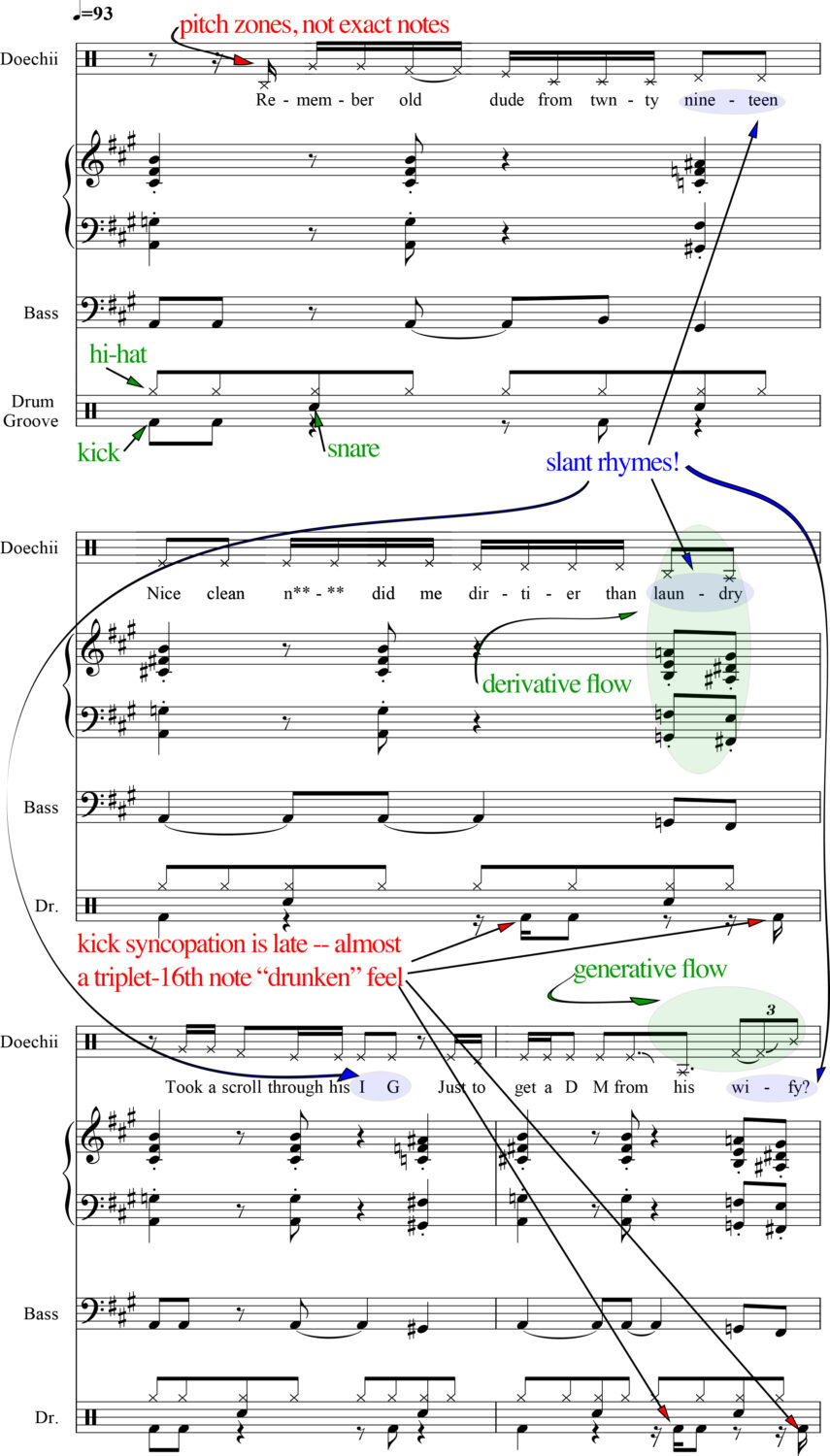

In “Denial Is A River,” Doechii synchronizes most of her energetic rap flow precisely with the underlying beat (derivative flow) — including with the slightly “drunken” kicks. But there are crucial, contrasting moments — often conversational — that move out of time (generative flow), with a Rakim-style slight swing in the 16ths. She displays a deeply intuitive sense of rhythm that allows her to move through varying degrees of swing and micro timing, creating natural rhythmic fluctuations so the rap flow helps tell the story naturally. See Figure 6 below.

Figure 6: Part of Verse 1 — Syncopation, Metrical Techniques, and Pitch in Doechii's Flow

While we commonly don’t think of Doechii’s style of hip-hop as a source of melody, the way rappers employ pitch changes in their vocal delivery is vital. For example, Doechii’s use of pitch (and rhythmic) variation going into the line, “from his wifey” provides stark counterpoint to the style of flow preceding it. The regular 16th-note flow gives way to a loose, off-the-grid feel with a contrasting pitch rise — reflecting a crucial moment in the song’s storyline. Robert Komaniecki at the University of British Columbia published a paper in 2020 titled, “Vocal Pitch in Rap Flow,” in which he describes, among other things, the kind of exaggerated declamation we hear Doechii delivering here.

The entire “Denial Is A River” song represents a superb blend of various kinds of rap flows, as Doechii cruises effortlessly from one end of the derivative-generative rhythmic continuum to the other — at times reinforcing the underlying beat’s rhythmic structure, and at other times subverting it in in virtuosic ways. A lot of skill goes in to hiding the seams of the complex rhythmic patterns she’s stitched together. See Figure 7 below.

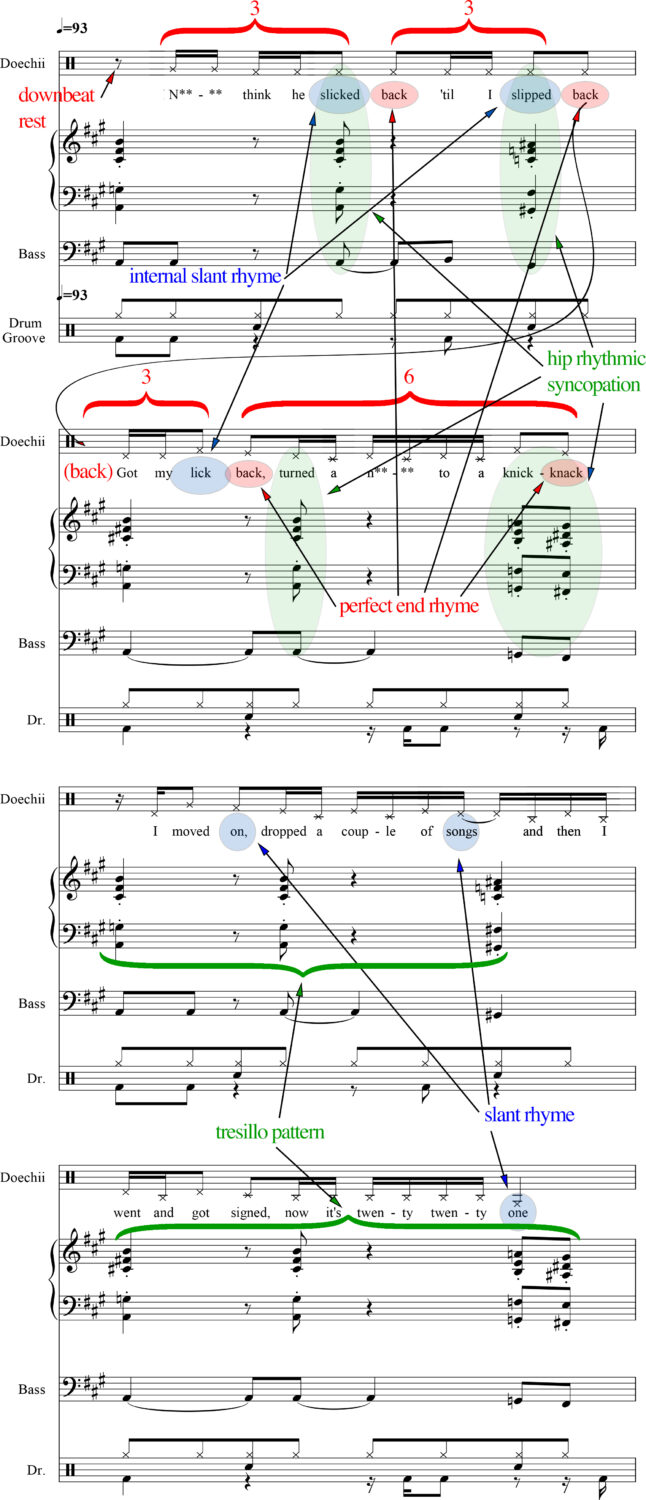

Figure 7: Hip Syncopations and Rhyming Schemes in Doechii's Flow

Note the asymmetrical phrase lengths of Doechii’s vocal lines in the first two bars of Figure 7 and how they interact with the tresillo rhythm (3+3+2) in the chord syncopation. The song is in 4/4 meter, but the downbeat rest coupled with rhythmic phrases comprising groups of three 8th notes further punctuates the cross-beat cell. The internal rhymes falling on unexpected beats impart a hip, stylish musicality to the whole verse — making it feel more fluid just when the song might otherwise start to feel stiff (if the assonances and rhythmic placement were line up too predictably). The words “slicked,” “slipped,” and “lick” represent a kind of imperfect “slant” rhyme internal to the phrases, and when the perfect “back”/”knack” rhyme arrives, sewing it all together, it lands unexpectedly due to the surprising syllabic stresses and the alliteration of “knick-knack” grabbing our attention. It’s so good.

Doechii With A Live Band

If you haven’t already, check out Doechii’s Tiny Desk Concert featuring her smokin’ 10-piece all-female band. You’ll hear “Denial Is A River” and other tunes with expanded harmony, walking bass lines, and impeccable live vocals.

A Closing Note on Music Notation

Dr. Robert Komaniecki popularized the idea of using “pitch zones” to represent rap vocals, and I’ve employed a similar approach in my transcriptions. The notes I put on the 5-line staff signify approximately where I hear Doechii’s voice, and these pitches are all relative (you shouldn’t assume they’re exact). Please consider these transcriptions to be a general representation of her vocal performance, not a precise document of it.

Additionally, I think we should keep in mind that Western music notation was conceived for Eurocentric music traditions. As such, it can be challenging to represent the musical ideas of other traditions (e.g., Indian classical music, with its raga system) using this notation. In his paper “Representing African Music,” CUNY professor Kofi Agawu cautions specifically about using Western notation to capture concepts in African or Afrodiasporic music. For now, it’s the best tool I have — so I’ve used it here while being mindful of its limitations. If you have other suggestions moving forward, please post them in the comments below.