Why Do You Hate Jazz?

Sheldon Abba

I started listening to jazz when I was around 15. My entry point was a common one: Miles Davis’ Kind Of Blue, which I bought on cassette for $5.99. I also heard John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme early on, after which I started gradually, haphazardly picking up albums here and there with no real method or guide; I would just hear about something somewhere — and this was pre-internet, and I wasn’t reading jazz magazines, so I was mostly limited to what I found out about from Rolling Stone or Spin — and try to find it in my local record store or grab something from my local library.

My mom was always pretty tolerant of my musical tastes. She wouldn’t let me play AC/DC in the house, because she hated Brian Johnson’s voice, but she thought Iggy Pop had a pleasing baritone, so he was OK. Most punk was fine, Judas Priest and Motörhead too, and there were even some things we bonded over, like Talking Heads’ Stop Making Sense and New Order’s Substance 1987. But when she heard Miles Davis coming from my room, she said one of the funniest, meanest things I’ve ever heard. “You know,” she told me, “jazz is music for people who think they’re smart.”

I thought about that line a lot while reading Andrew Berish’s Hating Jazz: A History Of Its Disparagement, Mockery, And Other Forms Of Abuse (University of Chicago Press, 2025). See, jazz is subject to disdain, scorn and ridicule far out of proportion to its commercial stature, to the point that it’s almost weird at times. Take, for example, this standup routine by Paul F. Tompkins.

It’s funny, because Tompkins is a skilled comedian with a highly developed comic persona. He’s not some knuckle-walking douchebag — can you imagine, say, Joe Rogan trying to do a joke about jazz? It’s easy to flip the routine on its head and believe Tompkins might be someone who does like jazz in his offstage life poking fun at the music’s more absurd aspects. Because yeah, I’ve been in clubs where musicians have played something that entertains themselves and leaves the rest of us going, “Yeah, okay, I guess that was cool…”

This joke is one of the things Berish talks about in his book, along with the exchange “You’re not stupid. Jazz is stupid!” “Yeah — just play the right notes!” from The Office, and an infamous New Yorker story presented as an interview with legendary saxophonist Sonny Rollins where “he” says things like, “We always dressed real sharp: pin-stripe suits, porkpie hats, silk ties. As if to conceal the fact that we were spending all our time playing jazz in some basement.”

That piece, originally published in 2014, provoked a wave of fury in the jazz community like nothing I’ve ever seen. Everyone who shared it on Facebook (and oh, did it get shared on Facebook) said something like “This piece is listed as humor in The New Yorker, but it doesn’t seem all that funny” or “I expect better from The New Yorker. But I won’t in the future” or “I hope Rollins sues them for this.”

Me? I thought it was one of the funniest things I’d read in the magazine years. To me, it was a hilarious, biting look at the dark side of the artistic temperament and the dismal fate awaiting most artists in a capitalist society.

But I suspect that the jazz critics who got so angry about the piece reacted that way because they’ve devoted even more decades than I have to listening to jazz, learning its history, interviewing the players, and writing about it, and they’ve done so from the perspective common to most jazz critics: that the music they like is great art, much more than mere entertainment, and deserves the highest honors our culture can bestow, all the time. It should certainly never be poked fun at or satirized — that’s for performers they think of as lesser, like Miley Cyrus or whichever other pop figure they happen to have somehow heard of. (Your average jazz critic’s unfamiliarity with contemporary pop culture would make a normal person weep with baffled laughter.)

I remember reading something a long time ago to the effect that you could tell when an ethnic group had successfully begun the process of assimilating into American society when they started to become the subject of jokes in movies. Not hostile, racist, dehumanizing jokes, but jokes poking welcoming fun at these new people and their weird folkways.

Jazz fans should welcome jokes about their music’s unlistenability and dismal commercial status. Why? Because it proves people still give enough of a fuck about jazz to make fun of it. Do you think they would have written a satirical interview with Jimmy Sturr, complaining about how awful the accordion sounds and how much he hates polka? Do you think anyone would have read it if they had?

But Berish’s book isn’t just about jokes at jazz’s expense. He also deals with a broader hostility to jazz, which takes many forms. There are musicians who hate jazz because of what they perceive as its innate qualities, so they’ll say things like, “Oh, those guys can play a million notes, but they can’t write a song…” There are the social conservatives of the pre-rock ‘n’ roll era who hated jazz because they saw it as licentious, or the music of Black people corrupting innocent white children. Then there are people who hate it because they think of it as snobby, elitist music. So Berish’s challenge was to bring all of these things under one umbrella, and he does so quite well.

“There were kind of two criteria that guided what I chose to focus on,” he told me when I called him up. “I wanted people who used the word ‘hate.’ That seems really important because of the ambivalence and ambiguities of that word — what’s interesting about hate is that it both represents everything that’s really awful in the world, you know, misogyny, racism, violence, all bad, bad stuff, and at the same time, it’s just a very heightened way of saying you don’t like something, like ‘I hate rice pudding’ or ‘I hate that Christmas sweater,’ right? So that was important; the other was that people had to be using the word ‘jazz’ because …I think we sometimes get down in the weeds if I’m teaching music history class and trying to define it or explain the different definitions, but it’s really that the word takes on all this power and it creates all these meanings to it, right? And it gets deployed in all these different ways. To me, that’s not a problem. That’s what’s interesting …is kind of tracing the debate, not deciding who’s right or who’s wrong, but it’s just super interesting that nearly everyone from Louis Armstrong to Duke Ellington to Ornette Coleman to Cecil Taylor to everyone has an opinion about it, because the word has so much accreted to it. I don’t know a good metaphor, but everyone can kind of turn around and look at it and see the thing that they want to see or the thing they wish they couldn’t see in the word.”

The first chapter deals with issues of taste, race, and other social/societal factors that have led to criticisms of jazz from the 1920s to the present day, exploring how the treatment of jazz has often been a synecdoche for broader racial tensions. The second looks at ways in which jazz has been satirized over the years, including the aforementioned Tompkins joke, the New Yorker piece, BuzzFeed articles, and the Twitter account @JazzIsTheWorst. The third chapter is perhaps the most interesting, as it deals with intra-musical hostilities, including Pat Metheny tearing into Kenny G, Stanley Crouch attacking Miles Davis, and Davis ripping apart Cecil Taylor in a DownBeat blindfold test (“Is that what the critics are digging? Them critics better stop having coffee”).

In discussing why people claim to hate jazz, or why they express more specific complaints about aspects of it, the issue of race inevitably arises. Whether it was white racists attacking it as jungle music in the 1920s or, decades later, Anthony Braxton’s music being dismissed as not Black enough, it’s always fraught territory. “I think the book was also a way to kind of confront race, because it’s obviously not a very fashionable moment to talk about this, but you can’t… it’s important both empirically to the birth of the music and its history, but jazz has also become a kind of signifier, a way of negotiating a kind of racial color line, a kind of racial boundary, whether it’s white musicians looking for a different aesthetic or they hear something that feels new and different from their side of the color line, or if you’re African-American, musicians or fans or listeners seeing something in jazz that is really important and connects to a broader history as well, at every moment, jazz has been this window, this way of negotiating these racial lines… drawn historically between black and white, and it’s important to understand that and kind of see the music that way.”

Another important thing to remember is that good satire is about “punching up.” Culturally speaking, a shot at jazz is exactly that. It may be dead from a record-sales standpoint, and its stars may mostly play tiny clubs, but on the cultural ladder, jazz is several rungs above rock and pop. It’s considered important music. Of course, that’s helped doom its sales, because nothing sends albums flying off the shelves like guilting people into listening to something that’s supposed to be good for them… but congratulations, jazz critics, you won the battle for prestige. The music you love has been 100% accepted by the elite. It’s the soundtrack to arts benefits, awards shows (the Oscars still big-band up the music from the previous year’s releases), and any scene in a film or TV show where someone needs to be portrayed as classy… or old.

Berish agrees with me on this… sort of. “I think a lot of people making fun of jazz, they feel like they’re punching up at something that has achieved a kind of cultural status that that they feel — if you’re the critic or you’re making the joke, that it’s undeserved and you know, who really likes this music? No one really likes it. You go home, do you put it on? You know, you say you like it because it has cultural prestige and distinction. I do point this out. But from the other side, from within the jazz world broadly speaking, it feels like — and I think this explains some of the reactions to the Sonny Rollins piece — that you are punching down. You think you’re punching up, but jazz achieved its status through a struggle, it was really hard and it was years and years of people making the case and arguing, through commercial ups and downs, so it’s kind of this achievement but yet it feels very precarious in a way, even though jazz is at an institutional place in American cultural life [where] it’s probably stronger than it’s ever been. I mean, you have Juilliard, you have the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, SFJazz, there are jazz programs at many, many colleges and universities and high schools. There’s something interesting there … there’s that weird disconnect or dissonance between people who feel like they’re punching up, but the people on the other side, feel like they’re kind of punching down.”

Debates about jazz’s role in American society and the broader musical world will likely persist as long as people have ears to hear. And there will never be a consensus. Hating Jazz is a fascinating — and fun — book to read because by providing a mix of history, sociological analysis, and theorizing, it allows us to see jazz as something worth getting excited about.

TAKE 10

Alune Wade - "Boogie And Juju"

Alune Wade is a bassist from Senegal whose music tosses jazz, soul, funk, rock, and multiple African sounds into a thick stew. His new album New African Orleans makes the connections he’s been drawing for years more explicit than ever, bringing in musicians from New Orleans and across the African diaspora, including drummer Herlin Riley, percussionist Weedie Braimah, and Nigerian talking drum player Olaore Muyiwa Ayandeji. The album includes versions of Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child (Slight Return),” Fela Kuti’s “Water No Get Enemy,” Herbie Hancock’s “Watermelon Man,” and Dr. John’s “Gris Gris Gumbo Ya Ya,” along with Wade’s own compositions. “Boogie And Juju” combines the two styles noted in its title — Nigerian juju music and Southern boogie-woogie — while adding Cameroonian rhythms and football chants from Senegal and Brazil, with a New Orleans horn section (including tuba) and a lot more. That’s a lot, but the whole thing comes together beautifully. (From New African Orleans, out now via Enja/Yellowbird.)

Arcanum - "Folkesong"

Arcanum is a new quartet formed by two Norwegians (trumpeter Arve Henriksen and saxophonist Trygve Seim), Swedish bassist Anders Jormin and Finnish drummer Markku Ounaskari. Each has played with one or more of the others before, but this is their first recording all together, and the result reminds me of classic ECM titles like Jan Garbarek’s Witchi-Tai-To or Codona’s albums. Henriksen has an extraordinary way of playing the trumpet that makes it sound almost like a flute, and when this is combined with Seim’s ultra-gentle saxophone it’s like hearing Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry playing lullabies for babies. Behind them, Jormin and Ounaskari generate soft but persistent rhythm, occasionally augmented by subtle electronics or extra percussion. “Folkesong” sounds like the kind of thing Cherry would have come up with when he was living in Sweden in the late Sixties and early Seventies: free-ish, but direct and heartfelt. (From Arcanum, out now via ECM.)

Brandon Woody - "Perseverance"

Brandon Woody is an up-and-coming trumpeter newly signed to Blue Note. He’s originally from Baltimore, which is why he’s depicted in front of a stretch of row houses on the cover of his debut album, For The Love Of It All. He’s operating like a modern artist, and good for him; he’s had brand partnerships with Calvin Klein, Nike, Saucony and others, and has scored several independent films. His band Upendo, heard throughout the album, came together in 2017 while he was still in school, and features keyboardist Troy Long, bassist Michael Saunders, and drummer Quincy Phillips, with Vittorio Stropoli contributing synthesizer here and there. Woody is a powerful trumpeter in the vein of Chief Adjuah or players from a previous generation like Freddie Hubbard and Donald Byrd, and “Perseverance” has the romantic quality of Quiet Storm R&B, its big, passionate melody allowing Woody to show off his rich, burnished tone. (From For The Love Of It All, out now via Blue Note.)

Chris Cheek - "Smoke Rings"

Analog Tone Factory is a new label that records exclusively to tape. Saxophonist Chris Cheek, guitarist Bill Frisell, bassist Tony Scherr, and drummer Rudy Royston went into the Power Station studio in New York and made this album with everyone in the same room, and the results (even heard as downloaded digital files, ha ha) sound amazing. Frisell is in my left headphone, Royston in my right, with Cheek and Scherr in the middle, and the performances have an old-school, late-night vibe as though they recorded them at two AM instead of at a daytime session like the professionals they are. “Smoke Rings” is a simple, melodic standard that’s been recorded a million times, notably by guitarist Les Paul and his wife Mary Ford, and the quartet play it in a relaxed style that honors the melody while leaving just enough room for some smooth and tasteful solos from Cheek and Frisell. (From Keepers Of The Eastern Door, out 5/23 via Analog Tone Factory.)

Cyrus Chestnut - "Autumn Leaves"

Stacy Dillard is one of my favorite saxophonists, but if you don’t live in New York and don’t make a habit of going out to small, hardcore jazz spots, you might not even know his name. He made a couple of albums in the 2000s (check out 2008’s One and 2011’s Good And Bad Memories) but seems more interested in gigging and sideman work. He’s a straightahead player with a fine sense of melody and an essential grace that reminds me of classic saxophonists like Hank Mobley and George Coleman, and he’s the featured horn on this album by pianist Cyrus Chestnut that, unsurprisingly given its title — Rhythm, Melody And Harmony — is all about simple verities. On this version of the standard “Autumn Leaves,” bassist Gerald Cannon and drummer Chris Beck lay down a gentle, swinging rhythm over which Chestnut and Dillard take a casual journey through the tune. (From Rhythm, Melody And Harmony, out now via HighNote.)

Gilad Hekselman - "Be Brave"

Guitarist Gilad Hekselman has released his latest album entirely independently; the LP is available through Diggers Factory, a company that presses vinyl on demand in limited editions. He recorded it in December 2023, with bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Marcus Gilmore; it includes six of his own compositions and versions of Burt Bacharach’s “Alfie” and Nachum Heiman’s “Like A Wildflower.” I know Hekselman best from his time in flugelhornist John Raymond’s trio Real Feels; they combined simple, almost folkish jazz tunes with instrumental versions of indie rock songs. The music on Downhill From Here is more conventionally “jazz guitar,” but with occasional bursts of spikiness. “Be Brave” begins with a gently strummed melody, as Grenadier and Gilmore create a surprisingly active rhythm bed; in fact, the bassist seizes the spotlight for much of the early going. Eventually, though, Hekselman steps forward and goes off, propelled by twitchy, rattling drums. (From Downhill From Here, out now via Gilad Hekselman.)

Joe Lovano - "Golden Horn"

On his latest ECM release, Boston-based saxophonist Joe Lovano is backed by the Polish trio led by pianist Marcin Wasilewski, with bassist Slawomir Kurkiewicz and drummer Michal Miskiewicz. This is their second release together, following 2020’s Arctic Riff, and the trio also used to play with Polish trumpeter Tomasz Stanko in the early 2000s. “Golden Horn” is a composition Lovano’s recorded several times, going back to the ’80s. Here, it’s performed in a spiritual jazz mode, beginning with shakers and drums being slapped with brushes so as to sound like congas; Wasilewski plays a simple four-note figure, echoed by Kurkiewicz in a manner recalling certain classic John Coltrane Quartet recordings. When Lovano enters on saxophone, things get more lyrical, but he sounds like a bear waking up from a nap at first, yawning and stretching. Then everyone falls into line and things get more passionate, but always anchored by the groove. (From Homage, out now via ECM.)

Luke Stewart Silt Remembrance Ensemble - "Silt Remembrance"

The Silt Remembrance Ensemble is bassist Luke Stewart’s way of combining two of his bands, the Remembrance Quintet (with Daniel Carter and Jamal Moore on reeds, Chris Williams on trumpet, and Tcheser Holmes on drums) and the Silt Trio (with Brian Settles on saxophone and Chad Taylor on drums), into one new unit. This album, recorded live in the studio, features Carter, Settles, Moore, and Taylor, with a couple of poets on individual tracks. Though each group has an album to its name, this set seems to be new material. It’s not just a document of the performance, either; the music has been re-sequenced to create a full artistic statement. “Silt Remembrance” is propelled by a tumbling Taylor beat, over which the three saxophonists take free-but-anchored solos and let their lines wind around each other as the rhythmic energy grows and grows with each passing moment. It’s heavy, thrilling stuff. (From The Order, out now via Cuneiform.)

Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra Led By Horace Tapscott - "Equinox"

Pianist Horace Tapscott led the LA-based Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra from 1961 until his death in 1999. Although he recorded with smaller groups, the PAPA performed often, and Tapscott intended them to be a voice within the community rather than competing in the commercial marketplace. On this album, a 12-member incarnation of the ensemble that included trumpet player Lawrence “Butch” Morris, who would later become a conductor and leader of his own large ensembles, can be heard playing at Widney Career Preparatory & Transition Center, a vocational high school for special education students. The set list includes versions of Pharoah Sanders’ “The Creator Has A Master Plan” and the spiritual “Motherless Child,” but it all kicks off with a 25-minute version of John Coltrane’s “Equinox.” Tapscott’s piano is a solid anchor, laying down chords like bricks in a wall as the various horns take turns in the spotlight. (From Live At Widney High December 26th, 1971, out now via The Village.)

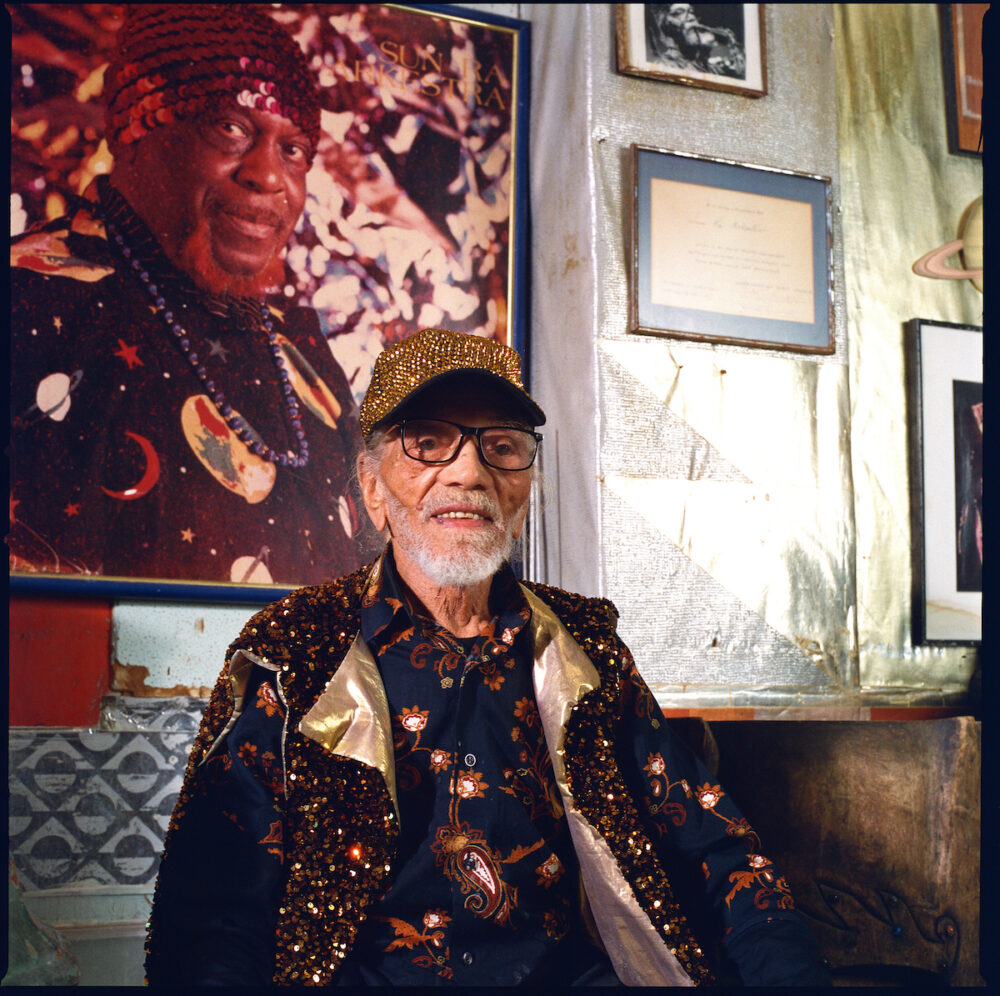

Marshall Allen's Ghost Horizons - "Slip Stream"

Marshall Allen’s second century of life is off to a roaring start. He’ll turn 101 on May 25 and has been playing with the Sun Ra Arkestra since 1958, leading it since 1995. But recently, he’s been getting recognition as an individual artist. He was named an NEA Jazz Master this year, alongside pianists Marilyn Crispell and Chucho Valdés and critic Gary Giddins. And he’s putting out records under his own name — the studio album New Dawn was released in February, and now we get the double LP Live In Philadelphia.

This set was culled from nine performances at Solar Myth between November 2022 and January 2024. The bands all featured Allen on alto sax, synthesizer, and EVI (Electronic Valve Instrument), and Arkestra guitarist DM Hotep, but a ton of special guests filled out the lineups, including bassists William Parker, Luke Stewart and Eric Revis; drummers Chad Taylor and Tcheser Holmes; saxophonists James Brandon Lewis, Elliott Levin, and Immanuel Wilkins; electronic noise weirdos Wolf Eyes; and more.

“Slip Stream” was recorded December 26, 2023 and features keyboardist Brian Marsella, Wilkins on saxophone and electronics, and Taylor on drums. The multiple synths and electronic noise-making devices create a kind of burbling psychedelic cloud not unlike some of Rob Mazurek’s groups (Taylor is a regular Mazurek partner), but Wilkins’ saxophone cuts through it all, shifting between speedy post-bebop lines and keening slower phrases. The music has a thick pulse reminiscent of late ’60s electric Miles, less cosmic than Ra’s work and more grounded in that liminal zone between soul jazz and early fusion. It’s just one of the many styles and sounds Allen and his compatriots explore on this double LP. There are old-school swinging tunes, journeys into near-total electronic abstraction, howling free jazz eruptions, and everything else you can think of. Like his former boss/spiritual guide, Marshall Allen seems determined to play something new every time he lifts his horn or guides an ensemble off the ground. Long may he run. (From Live In Philadelphia, out now via Otherly Love and Ars Nova Workshop.)

OUTWARD BOUND

@dearlyblossom Miles always makes me feel better when it’s rainy outside. This is some of his solo on So What from Kind Of Blue that I learned today. ☔️ Does this song sound like a rainy day to you or is it just my phytohormones? 🌸🤨 #milesdavis #miles #sowhat #kindofblue #jazzvocalist #jazzsinger #puppetsofinstagram #puppetry #nycjazz ♬ original sound – dearlyblossom