In The Number Ones, I’m reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart’s beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present. Book Bonus Beat: The Number Ones: Twenty Chart-Topping Hits That Reveal the History of Pop Music.

I wanted to believe. On the very first day of 2019, an unknown-to-me Charlotte rapper came out with a ridiculously stupid video for a ridiculously fun single called “Walker Texas Ranger.” The song had a simple, hyperactive plink-plonk beat, and the rapper attacked with effortless precision, sounding like he was having the best time in the world. In the video, he wore a cowboy hat and a leather jacket, and he drove his truck off a cliff because he was paying too much attention to a lady’s butt on his phone screen. He kept rapping and dancing as the car plummeted through space. He then crawled up out of a ravine unharmed, robbed a blind man, and won a deep-woods kung fu battle. I love shit like this.

From the moment that he appeared on my computer screen, DaBaby came off as a throwback to a time in rap that I loved. He was sharp and technical and straightforward, and he rapped with the same hungry, horny, self-deprecating desperation as prime Ludacris. Every song felt like a shot of adrenaline. It was fun music, at a time when most of rap’s mainstream was pushing toward bleak melodic churn. In the 12 months after that “Walker Texas Ranger” clip dropped, DaBaby went on one of the all-time great rookie runs in rap history. He released two albums that year, and both of them hit. He showed up on tons of other people’s songs, and he upstaged those other people just about every time. Outside of Charlotte, precious few people had heard of DaBaby before January 1, 2019. By the end of the year, he’d been on 22 songs that charted on the Billboard Hot 100.

I was so excited about DaBaby. He was just really good at rapping! I love a rapper that’s really good at rapping, and I love it when that rapper can actually take hold of the zeitgeist and change the cultural energy around them. In the case of DaBaby, I found him so refreshing, so energizing, that I looked past a whole lot of red flags. He kept getting arrested and getting into fights for seemingly no reason. He said ugly shit in interviews and gave off little sense that he had any depth as a human being. He’d once killed a guy and gotten away with it. The first time I wrote about DaBaby, I learned about that killing while I was in the middle of writing the piece, and you can see me attempting to grapple with this extremely fun new rap star who might also be an extremely dark human being in something like real time. I didn’t know how to feel about it. I had no answers.

Music can do funny things to a person. Despite all the prevailing evidence that gifted musicians are often horrible people, I have a long history of mentally making excuses for these people and deciding that I still like them. Sometimes, those gifted musicians will turn a corner and realize that they need to adjust something in the way that they look at the world. Most of the time, though, the opposite happens. The darkness metastasizes, and it becomes impossible to ignore. The excuses disappear. That happened so quickly with DaBaby. It was like the entire world simultaneously decided that we’d all had enough of him. He was on top, and then he disappeared from view completely. This wasn’t a one-hit wonder situation. DaBaby cranked out three extremely successful albums in just over one year, and he became an omnipresent pop-chart figure. Then he did some fucked-up shit, and he was gone. Before that happened, though, DaBaby made the biggest song of his career, which was also the biggest song of lockdown summer.

DaBaby was around for years before his golden rookie year, and he wanted badly to get famous. He came from Charlotte, a huge city that had never produced a national rap star of any note. Other cities had entire scenes that could work as infrastructure for a young rising star. Charlotte didn’t have that. DaBaby was desperate to get noticed any way that he could. In 2017, he took himself out to SXSW in Austin, and he hung out on Sixth Street in nothing but a diaper, trying to get attention in classic freakshow fashion. I didn’t go to SXSW that year, so I didn’t see DaBaby out there in his diaper. But I’ve been to SXSW enough times to know that an aspiring rapper in a diaper wouldn’t turn anyone’s head on Sixth Street. I could’ve walked right past him and not even noticed. At least for one week out of the year, that’s what Sixth Street is like. DaBaby’s plan didn’t work, anyway. Instead, he just kept making good rap music until he was impossible to ignore. That’s usually the better plan.

Jonathan Lyndale Kirk isn’t originally from Charlotte. Instead, when DaBaby was an actual baby, he lived in Cleveland. (When DaBaby was born, Michael Jackson’s “Black Or White” was the #1 song in America.) Per an early Rolling Stone profile, DaBaby’s father served in Afghanistan and Iraq, and his mother worked for a finance company. DaBaby’s family moved to Charlotte when he was six. He graduated from high school there, and he went to college at UNC Greensboro for a couple of years before dropping out. It’s not entirely clear what he did between dropping out of school and taking off as a rapper. In interviews, he wouldn’t talk about that time, beyond vague statements about being “in the streets.” When he started making videos, though, he was wearing some expensive-looking jewelry. Infer what you will.

DaBaby started rapping under the name Baby Jesus in 2014, and he made some viral noise with a 2016 track called “Lightshow.” After a while, he changed his rap name to DaBaby because light sacrilege wasn’t working for him. He flooded the zone, cranking out mixtapes in his Baby Talk series and coming up with a sound and a persona that could translate to the larger world. By the time I learned who DaBaby was, he’d made 13 mixtapes. He figured out that he sounded best as an energy guy, hammering tracks with visceral silliness and making sure everyone knew that he didn’t take himself seriously even when his punchlines weren’t actually funny. The South Carolina producer Tahj Morgan, known professionally as JetsonMade, started collaborating with DaBaby in 2018, and his simple, bloopy funk complemented DaBaby’s athletic fast-rap approach perfectly. Video-directing team Reel Goats helped him establish his over-the-top, larger-than-life slapstick persona. Arnold Taylor, a big regional radio promoter, signed on as his manager.

As a rapper, DaBaby spent years developing a sound and a character on the Southern underground. He started to build an audience, doing strong YouTube numbers for someone who didn’t have a big company behind him. Apparently, he also made some enemies. In November 2018, just before he got famous, DaBaby was shopping for winter clothes with his kids at Walmart, and he got into a fight with a 19-year-old man and shot him dead. In a video that he posted after the killing, DaBaby claimed that the other guy had pulled a gun and tried to kill him. Police dismissed charges against DaBaby on self-defense grounds, and the death simply became part of his backstory. If DaBaby was torn up over the fact that he’d ended another human being’s life, he didn’t show it. Instead, he made occasional reference to it in his lyrics — little tossed-off lines about how nobody should test him because he might shoot somebody else. Again: red flags.

DaBaby’s regional buzz got big enough that Jay-Z’s Roc Nation company signed a deal to distribute his 2018 mixtape Blank Blank, and that set the table for “Walker Texas Ranger” to take off online. When people discovered that song, they also found that this guy had a years-deep catalog and at least a few other tracks that were nearly as catchy as that one. DaBaby’s style was the kind of thing that you could instantly pick up on. He would often start rapping at the moment that the beat dropped, never giving it any room to breathe. He could spit for long stretches, and he didn’t necessarily need hooks. But he could make hooks, anyway, slowing his flow up long enough to repeat something catchy a few times. Major labels rushed to sign DaBaby, and he quickly inked a big deal with Interscope. Then he crowed about that deal on “Suge,” a relentlessly catchy track that crossed over and reached #7 on the Hot 100. (It’s a 9.)

As “Suge” took off, DaBaby released Baby On Baby, his first proper album. It’s fast and relentless and barely half an hour long. It’s clearly a rush job, but that works nicely for it. That was really only the beginning of DaBaby’s blitz. DaBaby was part of that year’s XXL Freshman Class, and he blacked the fuck out in his XXL cypher, even outshining past and future Number Ones artist Megan Thee Stallion. That year, DaBaby appeared on big streaming songs from Megan, Post Malone, Chance The Rapper, and Trippie Redd, among others. DaBaby and the similarly monikered young rap star Lil Baby teamed up on a song that was naturally called “Baby,” and it peaked at #21.

In summer 2019, DaBaby’s fellow North Carolina rap star J. Cole assembled a bunch of his comrades to a studio camp to crank out the Revenge Of The Dreamers III compilation, and DaBaby probably had the best verse on the whole tape. (J. Cole, Lute, and DaBaby’s “Under The Sun” peaked at #44. Cole will eventually appear in this column.) Lizzo’s “Truth Hurts” finally shoved its way to #1 after DaBaby appeared on a remix. During that blitz, people started to point out that DaBaby was basically just making the same song, with the same flow, over and over again. He clearly hated when interviewers would ask him about that, but when he deigned to answer the question, he simply pointed out that the flow was working for him. He was right. In almost every situation, DaBaby’s collaborators were simply incapable of keeping up with him.

While DaBaby’s career was taking off, his father unexpectedly died. To hear him tell it, he got that news at the same time that he heard that Baby On Baby was #1 on the Apple Music streaming chart. Six months after Baby On Baby came out, DaBaby released another LP called Kirk. On opening track “Intro,” he rapped about the headfuck of experiencing tragedy and sudden success at the same time, and even there, he kept the breakneck pace up. But the biggest hit from Kirk was “Bop,” an even sillier song than “Suge.” I thought the dance-heavy “Bop” video was an absolute delight. The song reached #11, and both Baby On Baby and Kirk went platinum. A star was born.

DaBaby did not allow stardom to change the way he approached the world. Usually, that’s a good thing. You want newly successful people to remain rooted. In DaBaby’s case, though, it was a disaster. He kept getting into violent situations, and he kept trumpeting his own capacity for violence. When someone wouldn’t stop bothering him in a jewelry store, DaBaby beat the guy up so badly that his pants literally fell off, and then he posted the video online. (It looked staged.) Early in 2020, DaBaby was arrested for battery after allegedly robbing a promoter who hadn’t paid him enough. Two months later, he was caught on video slapping a female fan for putting her phone in his face while he was making his way to the stage in a Tampa club. This was not sustainable. Soon after DaBaby’s father’s death, his older brother also took his own life. DaBaby continued to experience serious trauma even after getting rich and famous, and I’m sure that contributed to what he was doing. He was still doing that shit, though. You can’t do that shit.

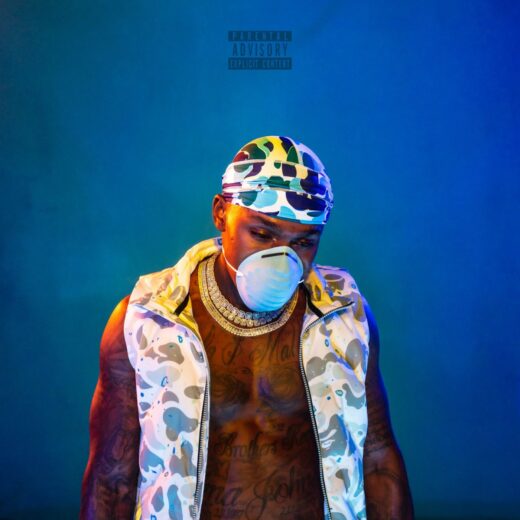

But the hits kept coming. Another six months after Kirk, DaBaby had another album ready to roll. He wanted to show people that he could rap in more than just his trademark attack-dog flow, so he tried incorporating more and more melody, which mostly killed everything distinctive about him. Blame It On Baby came out in April 2020, and it’s by far the least engaging of the three major-label records that DaBaby released in quick succession. That record is so tied to the early-pandemic moment that DaBaby wore a facemask on the cover. The song’s lead single was “Find My Way,” a boring country-flavored song with an endless 10-minute mini-movie video. That one only made it to #22. But a different song started getting TikTok buzz after the Blame It On Baby album came out in April 2020: “Rockstar,” his team-up with fellow newly minted rap star and former Number Ones artist Roddy Ricch.

“Rockstar” is the second rap song with that title that reached #1 on the Hot 100 in a surprisingly short stretch of time; it came just three years after the Post Malone/21 Savage song with the same title. That should give you some idea how original DaBaby’s “Rockstar” is. The song has none of the madcap bounce of DaBaby’s JetsonMade collaborations. Instead, it’s got a floaty, generic beat from Ross Portaro, a North Carolina producer who goes by the professional name SethInTheKitchen. (No, I don’t know why he calls himself that when his name isn’t actually Seth.) SethInTheKitchen had been collaborating with DaBaby since his mixtape days, and he produced a couple of tracks on the Kirk album. He’s responsible, in fact, for that album’s worst track, the bloodless Nicki Minaj collab “iPhone.” (It peaked at #43.) Seth’s “Rockstar” beat is built around a fluttering acoustic guitar that sounds extremely synthetic. DaBaby uses that beat to attempt his own version of his guest Roddy Ricch’s melodic singsong flow. He does just fine with that flow, but it’s not terribly compelling.

The song opens with a computerized whine and what sounds like ukulele strums, which then cohere into a florid acoustic-guitar figure. DaBaby softly mutters about how he pulls up. When the drums arrive, falling into the exact quasi-trap pattern that you’d expect, DaBaby’s singsong chorus arrives: “Brand new Lamborghini, fuck a cop car/ With that pistol on my hip like I’m a cop.” For someone who isn’t known as a singer, DaBaby can at least come up with a hook that’ll get stuck in your head all day. “Rockstar” sounds like a track with 15 songwriters, even though the only writers credited are DaBaby, Roddy Ricch, and SethInTheKitchen. Lyrically, the “Rockstar” chorus is just a half-asleep flex. DaBaby doesn’t even consider what rock stardom might mean even as much as Post Malone and 21 Savage did a few years earlier. Instead, the song gets its title from this lyric: “Have you ever met a real n***a rockstar?/ This ain’t no guitar, bitch, it’s a Glock!” But guitars and Glocks don’t look anything like each other. It’s some real first-take shit.

From there, DaBaby talks about how his gun talks sweetly to him and asks him to squeeze it. That’s standard cartoonish rap business, but it would go down a lot easier if the guy singing that hook hadn’t actually killed someone in real life. In his verse, DaBaby builds up to a double-time flow, doing a truly impressive Migos-style syncopated syllable-rush. He sounds a little softer and more melodic than on his most straightforward tracks, but he’s still talking about violence, even as he invokes his child: “PTSD, I’m always waking up in cold sweats like I got the flu/ My daughter a G, she saw me kill a n***a in front of her before the age of two/ And I’ll kill another n***a, too, ‘fore I let another n***a do somethin’ to you.” He says that like it’s heartwarming.

When Roddy Ricch shows up, he switches back and forth between rapping and singing, just as he’d done on “The Box” a few months earlier. Roddy changes flows with effortless ease, and he does it while talking about guns and violence, just like DaBaby. At the end of his verse, Roddy mentions a moment when he encountered some adversaries at a gas station and thought he was about to die. He says that he had $30,000 on him and that he was prepared to kill anyone who threatened him, but those unidentified opps didn’t actually want smoke with him. For all I know, that story is entirely true. It’s still very different from DaBaby talking about how he killed a guy in front of his toddler daughter on a #1 pop hit. DaBaby later said that he and Roddy recorded the song together in the studio after being mutual fans from afar. They had an all-night recording session, and the sun was up by the time they left.

DaBaby’s “Rockstar” lyrics didn’t bother me when the song was new. Maybe I’d already heard him say so many similar things on so many songs, or maybe he says them so quickly that they never quite registered until I sat down to write this. Maybe I’m just getting old. The thing that bothered me about “Rockstar” at the time was that it didn’t showcase the vitality that DaBaby brought to so many other tracks, that it was just another piece of streaming-ready Auto-Tuned melodic mush. As streaming-ready Auto-Tuned melodic mush goes, it’s solid. And again, I wanted to believe in DaBaby. But darker things were happening on that song.

Darker things were happening in America, too. On May 26, 2020, the Minneapolis cop Derrick Chauvin murdered George Floyd by kneeling on his neck until he was dead. The murder was captured on video. That killing, along with plenty of other unjustifiable police killings, led to a giant national groundswell of protest. For once, it seemed like the people of America were enraged enough to demand actual systemic change. That change never came. It turned into a bunch of corporations making empty gestures at solidarity and then doing everything they could to retract those gestures when Donald Trump came back into power a few years later. Maybe DaBaby was simply making his own empty gesture when he released the “BLM Remix” of “Rockstar” a few weeks after Floyd’s murder, or maybe he really had some shit that he needed to say.

DaBaby opens his own “Rockstar” remix with a new verse about police pulling him over, trying to embarrass him. He flashes back to past encounters with the law, and he speaks of it as a systemic thing, not as something that just happened to him: “As a juvenile, police pulled their guns like they scared of me/ And we’re used to how crackers treat us, now that’s the scary thing.” He declares solidarity with the people burning cop cars and calls them rock stars. It’s not exactly a coherent statement of protest, but it’s a rare example of a mega-popular artist engaging with the moment and putting his stamp on it. After that new opening verse, the rest of the song just plays out like usual, but the urgency of that opening verse supercharged the song. I think I heard the “Rockstar” remix more than the original version in the weeks after that.

DaBaby wasn’t the only rapper engaging with the protest movement that summer. His occasional collaborator Lil Baby released a one-off single called “The Bigger Picture,” which came out on the same day as the “Rockstar” remix. “The Bigger Picture” is a more direct, confused, outraged protest song, and it wasn’t attached to some larger product. Lil Baby shot the video out at the actual protests where he was marching. Plenty of other songs addressed that moment, but the “Rockstar” remix and “The Bigger Picture” were the ones that resonated on the pop charts. (“The Bigger Picture” peaked at #3. It’s a 9, and it’s Lil Baby’s highest-charting single as lead artist. As a featured guest, Lil Baby was on three songs that reached #2 — Drake’s “Wants And Needs” in 2021, Drake’s “Girls Want Girls” also in 2021, and Nicki Minaj’s “Do We Have A Problem?” in 2022. “Wants And Needs” is a 6, “Girls Want Girls” is a 3, and “Do We Have A Problem?” is a 5.)

“Rockstar” reached #1 after the remix came out. The song’s video didn’t arrive until the song had already been sitting at #1 for a while. It’s a violent action-movie fantasia that takes place in a zombie apocalypse. Reel Goats direct, and DaBaby and Roddy Ricch run through a forest, sniping zombies and doing John Wick shit. DaBaby’s baby daughter makes a cameo. I like the bit where zombies try to play instruments. The video goes on for a really long time, with a making-of featurette during the end credits and shit.

At least in terms of the pop charts, DaBaby’s peak happened when “Rockstar” was at #1. During that strech, he also appeared on the #2 song in America — more on that below. At the same time, DaBaby and Lil Baby guested on the late New York rapper Pop Smoke’s posthumously released “For The Night,” which reached #6. (It’s a 6.) Blame It On Baby went platinum, just like DaBaby’s two previous albums.

In October 2020, Dua Lipa got DaBaby to appear on a remix of her single “Levitating,” and he was in the video and everything. “Levitating” never reached #1, but it went on to become the biggest Billboard hit of 2022; we’ll get into that whole saga in a future column. But while “Levitating” was in the middle of its pop-chart run, radio stations stopped playing the version with DaBaby on it. In July 2022, DaBaby performed at the Rolling Loud festival, and he hit the crowd with some nakedly homophobic stage banter. This is what he said: “[If] you didn’t show up today with HIV/AIDS or any of them deadly sexually transmitted diseases that’ll make you die in two to three weeks, then put a cellphone light in the air! Ladies, if your pussy smell like water, put a cellphone light in the air! Fellas, if you ain’t sucking dick in the parking lot, put a cellphone light in the air!”

What followed was a perfect demonstration of what not to do in this extremely avoidable situation. First, DaBaby attempted to defend his stage banter on Instagram, insisting that his gay fans “don’t got AIDS” and “take care of themselves.” Then he posted a defensive half-apology, complaining about the backlash while he did it. Finally, he put up another apology, this one still self-pitying but seemingly written by a publicist, and then deleted it soon afterwards. Dua Lipa denounced him. Tons of festivals dropped him from their lineups. While performing at Hot 97 Summer Jam, DaBaby complained about “crybabies.” Then he came out at one of Kanye West’s Donda listening events, standing there silently with West and Marilyn Manson, who’d been accused of sexual abuse many times, as if they were three heroes of free speech. It was so stupid and so self-important. The fact that DaBaby had actually killed a guy didn’t interfere with his pop stardom, but this rolling slow-motion series of PR disasters really did it.

Music is an emotional thing. You form bonds with the people you listen to, and you make assumptions about who they are. It’s illusory and parasocial, but that’s just how it works. DaBaby showed up with a great smile, a catchy approach, and a whole lot of energy, and then he spoiled all his own momentum. His fall from grace probably would’ve happened anyway. He couldn’t keep up the momentum of his rookie year, and he couldn’t adjust his style to anything deeper or more interesting. He didn’t really have anything to say. He didn’t make himself appealing. He kept getting arrested, and he reportedly shot someone else, an intruder at his North Carolina house, in 2022. Once again, he wasn’t charged, though he was charged for battery in a couple of unrelated incidents. He was about to fall off. He just fell off more dramatically than anyone expected. DaBaby was a star, and then he wasn’t.

Over the next year, I kept seeing viral posts about empty rooms at DaBaby shows, or about tickets being sold on steep discount. DaBaby kept making music, and some of it reached the Hot 100, but none of it resonated anything like what he was doing in 2019 and 2020. DaBaby’s biggest song after the 2021 kerfuffle was “Shake Sumn,” which peaked at #65 in 2023. That song would’ve been huge if it came out a couple of years earlier. It’s not impossible that DaBaby could come back someday. I wouldn’t be shocked if he somehow became a right-wing cause and rode that back to the top. (He did endorse Donald Trump last year.) But for now, it sure looks like DaBaby’s arc is complete. I wanted to believe, but he gave me nothing to believe in.

GRADE: 5/10

BONUS BEATS: For the BET Awards in 2020, DaBaby and Roddy Ricch sent in a remote performance of the “Rockstar” remix, dramatizing the song by opening with DaBaby on the ground, a cop’s knee on his neck. In the moment, it came off as an actual statement. Here it is:

THE NUMBER TWOS: Future Number Ones artist Jack Harlow’s all-star posse-cut remix of his bouncy, catchy flex “What’s Poppin” — with DaBaby, Tory Lanez, and Lil Wayne — peaked at #2 behind “Rockstar,” which means that DaBaby was on the top two songs in America at the same time. It’s a 9.

THE 10S: Lil Baby and 42 Dugg’s eerie, drawling, thudding summer anthem “We Paid” peaked at #10 behind “Rockstar.” Bro, it kept taking Ls, finally got itself a 10.

The Number Ones: Twenty Chart-Topping Hits That Reveal The History Of Pop Music is out now via Hachette Books. Keep that copy on your hip like you’re a… well, not a cop. Something else. I don’t know. Buy one here.